Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan - U.S. Fish and Wildlife ...

Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan - U.S. Fish and Wildlife ...

Final Comprehensive Conservation Plan - U.S. Fish and Wildlife ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

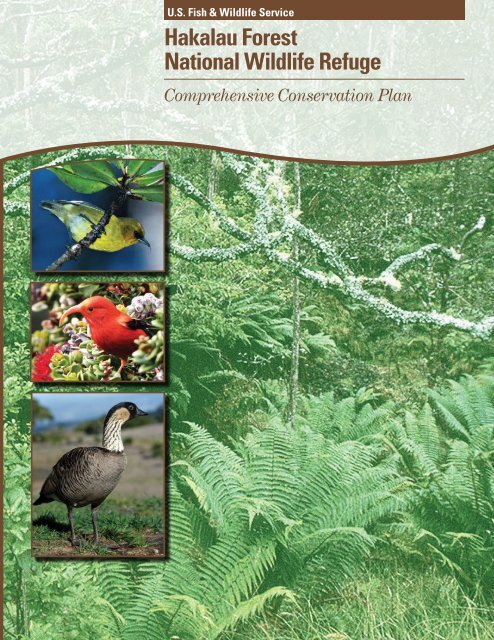

U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> & <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service<br />

Hakalau Forest<br />

National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>

A Vision of <strong>Conservation</strong><br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge (Ka Pu‘uhonua Waonahele Aupuni ‘o Hakalau)<br />

Aia nō i uka i ke kua ko‘olau o Mauna Kea ka pu‘uhonua waonahele aupuni ‘o<br />

Hakalau. He wahi kēia e hui ai kānaka e laulima ma o ke ka‘analike aku, ka‘analike<br />

mai i ka ‘ike, ka no‘eau, a me ka mana i mea e ho‘opalekana, ho‘oikaika, a ho‘ōla hou<br />

ai i ke ola maoli e noho ana ma ka waonahele. Ua kapa ‘ia ka inoa ‘o Hakalau no ka<br />

nui o nā haka e noho ‘ia e nā manu ‘ōiwi. I kēia lā ‘o Hakalau kekahi o nā home nunui<br />

no ka hui manu Hawai‘i ‘ane make loa. Kīkaha a‘ela nā manu, nā pua laha ‘ole ho‘i, i<br />

ka ‘ohu‘ohu o Hakalau a ma lalo iki e mūkīkī i ka wai pua ‘ōhi‘a. Ua nani nō ka ‘ikena<br />

a ‘upu a‘ela nō ke aloha no kēia ‘āina nei no nā kau a kau.<br />

On the windward slope of majestic Mauna Kea, midway between summit <strong>and</strong> sea,<br />

lies Hakalau Forest NWR, a place where people come together to laulima, “many<br />

h<strong>and</strong>s working together,” to share their knowledge, to share their skills, <strong>and</strong> to<br />

share their energy to protect, to enhance, to restore, <strong>and</strong> to respect Hawaiian<br />

wildlife. Known to Hawaiians as “place of many perches,” verdant rainforest<br />

supports the largest populations of endangered Hawaiian forest birds. Crimson,<br />

orange, yellow <strong>and</strong> green hued birds, the jewels of Hakalau, flit through the mist,<br />

pausing to sip nectar from ‘ōhi‘a lehua, inspire joy <strong>and</strong> wonder for present <strong>and</strong><br />

future generations.<br />

Kona Forest Unit (Ka Waonahele o Kona)<br />

Mai Mauna Kea nō a ka‘a i lalo, a hiki aku i Mauna Loa, ma laila nō ka waonahele o<br />

Kona, kahi e noho lewalewa ana nā ao ‘ōpua i ka ‘uhiwai e hō‘olu‘olu ana i ka ulu lā‘au.<br />

‘Ike ‘ia ka ‘io e kīkaha ana ma luna loa o ka papa kaupoku i ho‘owehiwehi ‘ia me ka<br />

limu. Ma lalo o ke kaupoku koa me ‘ōhi‘a, e ‘imi ana ka ‘alalā me kona hoa manu i ka<br />

hua‘ai, wai pua, a me nā mea kolokolo i mea ‘ai na lākou. Aia nō ma ka malumalu o nā<br />

ana kahe pele kahiko nā mea kanu kāka‘ikahi o ka ‘āina, a me nā iwi o nā manu make<br />

loa ma Hawai‘i. Kuahui maila nō nā hoa mālama ‘āina i ola hou ka nohona o nā mea<br />

‘ane make loa ma kēia ‘āina nui ākea.<br />

On leeward Mauna Loa, where the clouds kiss the slopes with cool gray fog, lies the<br />

Kona Forest. ‘Alalā <strong>and</strong> other Hawaiian forest birds forage for fruit, nectar, <strong>and</strong><br />

insects amongst the lichen-draped branches <strong>and</strong> canopy of the old-growth koa/‘ōhi‘a<br />

forest, while the ‘io soars overhead. In their damp darkness, ancient lava tubes <strong>and</strong><br />

cave systems shelter rare plants, archaeological resources, <strong>and</strong> the bones of extinct<br />

birds. <strong>Conservation</strong> partners collaborate to restore habitat for the native <strong>and</strong><br />

endangered species across the l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>s provide long-term guidance for management decisions <strong>and</strong> set<br />

forth goals, objectives, <strong>and</strong> strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes <strong>and</strong> identify the Service’s<br />

best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes<br />

substantially above current budget allocations <strong>and</strong>, as such, are primarily for Service strategic<br />

planning <strong>and</strong> program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment for<br />

staffing increases, operational <strong>and</strong> maintenance increases, or funding for future l<strong>and</strong> acquisition.<br />

‘Ōhi‘a tree<br />

©Lesa Moore

Executive Summary<br />

Executive Summary<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Hakalau Forest NWR Background:<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge (NWR) consists of the Hakalau Forest Unit <strong>and</strong> the Kona<br />

Forest Unit, collectively managed as the Big Isl<strong>and</strong> National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge Complex. The Hakalau<br />

Forest Unit was established in 1985 to protect <strong>and</strong> manage endangered forest birds <strong>and</strong> their<br />

rainforest habitat. Located on the windward slope of Mauna Kea, Isl<strong>and</strong> of Hawai‘i, this 32,733-acre<br />

unit supports a diversity of native birds <strong>and</strong> plants (27 of which are listed under the Endangered<br />

Species Act). The Kona Forest Unit was set aside in 1997 to protect native forest birds, the<br />

endangered ‘alalā (Corvus hawaiiensis, Hawaiian crow), <strong>and</strong> several listed plants. Located on the<br />

leeward slope of Mauna Loa, this 5,300-acre unit supports diverse native bird <strong>and</strong> plant species, as<br />

well as rare lava tube <strong>and</strong> lava tube skylight habitats.<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ning Process Summary:<br />

Initial preplanning activities began in 2007. This period included team development <strong>and</strong><br />

identification of management issues, vision, goals, <strong>and</strong> objectives. Public involvement began in 2009<br />

with the scoping process <strong>and</strong> publication of our notice of intent to prepare a CCP. This period<br />

involved mailings of the planning update, a news release <strong>and</strong> website posting, two public open<br />

houses, an interagency scoping meeting, <strong>and</strong> briefings of public officials. In 2010, the draft CCP/EA<br />

was developed <strong>and</strong> circulated for public comment. Notification of this document as well as<br />

solicitation of public comment during the 30 day comment period was accomplished through a<br />

planning update, a notice of availability in the Federal Register, a news release <strong>and</strong> website posting,<br />

holding of a public open house meeting, <strong>and</strong> circulating announcements via email <strong>and</strong> list serves.<br />

Refuge responses to public comments received were incorporated as part of Appendix K.<br />

Alternative Selected (Summary of Management):<br />

Three alternatives were analyzed during the CCP process <strong>and</strong> public comment review period.<br />

Alternative B (the Refuge’s preferred alternative) was chosen for implementation. This alternative<br />

focuses on protecting additional habitat; increasing management activities related to restoration <strong>and</strong><br />

reforestation as well as controlling threats such as feral ungulates, invasive weed species, predator<br />

mammals, <strong>and</strong> other pests; better focusing <strong>and</strong> prioritizing of data collection <strong>and</strong> research for<br />

adaptive management; <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ing public use activities <strong>and</strong> collaborative partnering.<br />

The vision (with Hawaiian translation) for Hakalau Forest NWR:<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge (Ka Pu‘uhonua Waonahele Aupuni ‘o Hakalau)<br />

Aia nō i uka i ke kua ko‘olau o Mauna Kea ka pu‘uhonua waonahele aupuni ‘o Hakalau. He wahi<br />

kēia e hui ai kānaka e laulima ma o ke ka‘analike aku, ka‘analike mai i ka ‘ike, ka no‘eau, a me ka<br />

mana i mea e ho‘opalekana, ho‘oikaika, a ho‘ōla hou ai i ke ola maoli e noho ana ma ka waonahele.<br />

Ua kapa ‘ia ka inoa ‘o Hakalau no ka nui o nā haka e noho ‘ia e nā manu ‘ōiwi. I kēia lā ‘o<br />

Hakalau kekahi o nā home nunui no ka hui manu Hawai‘i ‘ane make loa. Kīkaha a‘ela nā manu, nā<br />

pua laha ‘ole ho‘i, i ka ‘ohu‘ohu o Hakalau a ma lalo iki e mūkīkī i ka wai pua ‘ōhi‘a. Ua nani nō<br />

ka ‘ikena a ‘upu a‘ela nō ke aloha no kēia ‘āina nei no nā kau a kau.

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

On the windward slope of majestic Mauna Kea, midway between summit <strong>and</strong> sea, lies Hakalau<br />

Forest NWR, a place where people come together to laulima, “many h<strong>and</strong>s working together,” to<br />

share their knowledge, to share their skills, <strong>and</strong> to share their energy to protect, to enhance, to restore,<br />

<strong>and</strong> to respect Hawaiian wildlife. Known to Hawaiians as “place of many perches,” verdant<br />

rainforest supports the largest populations of endangered Hawaiian forest birds. Crimson, orange,<br />

yellow, <strong>and</strong> green hued birds, the jewels of Hakalau, flit through the mist, pausing to sip nectar from<br />

‘ōhi‘a lehua, inspire joy <strong>and</strong> wonder for present <strong>and</strong> future generations.<br />

Kona Forest Unit (Ka Waonahele o Kona)<br />

Mai Mauna Kea nō a ka‘a i lalo, a hiki aku i Mauna Loa, ma laila nō ka waonahele o Kona, kahi e<br />

noho lewalewa ana nā ao ‘ōpua i ka ‘uhiwai e hō‘olu‘olu ana i ka ulu lā‘au. ‘Ike ‘ia ka ‘io e kīkaha<br />

ana ma luna loa o ka papa kaupoku i ho‘owehiwehi ‘ia me ka limu. Ma lalo o ke kaupoku koa me<br />

‘ōhi‘a, e ‘imi ana ka ‘alalā me kona hoa manu i ka hua‘ai, wai pua, a me nā mea kolokolo i mea ‘ai<br />

na lākou. Aia nō ma ka malumalu o nā ana kahe pele kahiko nā mea kanu kāka‘ikahi o ka ‘āina, a<br />

me nā iwi o nā manu make loa ma Hawai‘i. Kuahui maila nō nā hoa mālama ‘āina i ola hou ka<br />

nohona o nā mea ‘ane make loa ma kēia ‘āina nui ākea.<br />

On leeward Mauna Loa, where the clouds kiss the slopes with cool gray fog, lies the Kona Forest.<br />

‘Alalā <strong>and</strong> other Hawaiian forest birds forage for fruit, nectar, <strong>and</strong> insects amongst the lichen-draped<br />

branches <strong>and</strong> canopy of the old-growth koa/‘ōhi‘a forest while the ‘io soars overhead. In their damp<br />

darkness, ancient lava tubes <strong>and</strong> cave systems shelter rare plants, archaeological resources, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

bones of extinct birds. <strong>Conservation</strong> partners collaborate to restore habitat for the native <strong>and</strong><br />

endangered species across the l<strong>and</strong>scape.<br />

The six goals (with Hawaiian translation) for Hakalau Forest NWR:<br />

Pahuhopu 1: E ho‘opalekana, mālama, a ho‘ōla hou i ka waonahele ma Mauna Loa ma ke ‘ano he<br />

wahi noho no nā mea a pau i mea e kū‘ono‘ono hou ai ka nohona o nā mea ‘ane make loa ‘o ia nō ‘o<br />

‘oe ‘o nā manu, nā ‘ōpe‘ape‘a, nā mea kanu, a me nā mea kolokolo ‘āina.<br />

Goal 1: Protect, maintain, <strong>and</strong> restore subtropical rainforest community on the leeward slope of<br />

Mauna Loa as habitat for all life-history needs to promote the recovery of endangered species (e.g.,<br />

forest birds, ‘ōpe‘ape‘a, plants, <strong>and</strong> invertebrates).<br />

Pahuhopu 2: E ho‘opalekana a mālama i nā ana kahe pele a me ke ola i ka puka mālamalama o nā<br />

ana kahe pele ma ka waonahele o Kona, e kālele ana ho‘i i ke ola o nā lā‘au ‘ōiwi.<br />

Goal 2: Protect <strong>and</strong> maintain lava tube <strong>and</strong> lava tube skylight habitat throughout the Kona Forest<br />

Unit, with special emphasis on their unique <strong>and</strong> endemic flora <strong>and</strong> fauna.<br />

Pahuhopu 3: E ho‘opalekana, mālama, a hō‘ola hou i ka waonahele ma ka ‘ao‘ao ko‘olau o Mauna<br />

Kea ma ke ‘ano he wahi noho no nā mea a pau a me ko lākou pono ‘oia nō ‘oe ‘o nā manu, nā<br />

‘ōpe‘ape‘a, nā mea kanu, a me nā mea kolokolo ‘āina.<br />

Executive Summary

Executive Summary<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Goal 3: Protect, maintain, <strong>and</strong> restore subtropical rainforest community, on the windward slope of<br />

Mauna Kea as habitat for all life-history needs of endangered species (e.g., forest birds, ‘ōpe‘ape‘a,<br />

plants, <strong>and</strong> invertebrates).<br />

Pahuhopu 4: E ho‘opalekana a mālama i ka ‘āina nenelu ma Hakalau.<br />

Goal 4: Protect <strong>and</strong> maintain wetl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> aquatic habitats (e.g., streams <strong>and</strong> their associated riparian<br />

corridors, ponds, <strong>and</strong> bogs) on the Hakalau Forest Unit.<br />

Pahuhopu 5: E ho‘opalekana a mālama i ka ‘āina mau‘u i mea e kāko‘o ai i ka ho‘ōla hou ‘ana i ka<br />

hui manu nēnē.<br />

Goal 5: Protect <strong>and</strong> maintain grassl<strong>and</strong> habitat to support nēnē population recovery.<br />

Pahuhopu 6: E ‘ohi‘ohi i ka ‘ikepili ‘epekema (waihona ‘ike, nānā pono, ‘imi noi‘i, ana ‘ike) e pono<br />

ai ka ho‘oholo ‘ana i ke ‘ano o ka ho‘okele ‘ana iā Hakalau ma Mauna Kea a me Mauna Loa.<br />

Goal 6: Collect scientific information (inventories, monitoring, research, assessments) necessary to<br />

support adaptive management decisions on both units of the Hakalau Forest NWR.<br />

Pahuhopu 7: E kipa mai ka po‘e malihini a me ka po‘e maka‘āinana no ka hana manawale‘a ‘ana i<br />

mea e kama‘āina ai lākou i ka nohona o ka waonahele a me ka ‘oihana mālama ma Hakalau.<br />

Goal 7: Visitors, with a special emphasis on experience gained through volunteer work groups <strong>and</strong><br />

local residents, underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>/or value the native forest environment <strong>and</strong> management practices at<br />

Hakalau Forest NWR.<br />

Pahuhopu 8: E ho‘opalekana a mālama i nā kumu waiwai a me nā wahi pana Hawai‘i no ka<br />

ho‘ona‘auao ‘ana i nā hanauna o kēia wā a me ka wā e hiki mai ana.<br />

Goal 8: Protect <strong>and</strong> manage cultural resources <strong>and</strong> historic sites for their educational <strong>and</strong> cultural<br />

values for the benefit of present <strong>and</strong> future generations of Refuge users <strong>and</strong> communities.

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

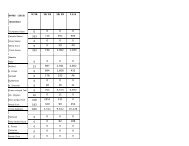

The objectives <strong>and</strong> major management strategies:<br />

Objectives CCP Action<br />

1.1: Restore <strong>and</strong> Protect Native<br />

Montane Wet ‘Ōhi‘a Forest<br />

(2,000-4,500 ft elevation) at KFU<br />

1.2: Restore, Protect, <strong>and</strong> Maintain<br />

Native Montane Mesic Koa/‘Ōhi‘a<br />

Forest<br />

(4,500-5,800 ft elevation) at KFU<br />

1.3: Protect, Maintain, <strong>and</strong> Restore<br />

Native Dry Koa/‘Ōhi‘a/Māmane Forest<br />

(5,800-6,100 ft elevation) at KFU<br />

1.4: Develop <strong>and</strong> Implement<br />

Propagation <strong>and</strong> Outplanting Program<br />

at KFU<br />

1.5, 5.3: Investigate <strong>and</strong> Initiate<br />

L<strong>and</strong>scape-level Habitat <strong>Conservation</strong><br />

Measures<br />

2.1: Protect & Maintain<br />

Lava Tube <strong>and</strong> Skylight Communities<br />

at KFU<br />

3.1: Protect <strong>and</strong> Maintain Native<br />

Montane Wet ‘Ōhi‘a/Uluhe<br />

(Dicranopteris sp.) Forest (2,500-4,000<br />

ft elevation) at HFU<br />

3,000 acres. Remove ranch debris. Build <strong>and</strong> maintain<br />

17 mile ungulate-proof fence. Remove pest animals.<br />

Eradicate/control invasive plants. Conduct annual invasive<br />

plant survey; conduct survey for pest animals (based on<br />

surveys control threats). Outplant threatened <strong>and</strong> endangered<br />

(T&E) plants in units 2 <strong>and</strong> 3 <strong>and</strong> build site specific fencing<br />

for these plants.<br />

1,800 acres. Remove ranch debris. Build <strong>and</strong> maintain<br />

fence, eradicate/control invasive plants, <strong>and</strong> remove pest<br />

animals. Conduct annual invasive plant survey; conduct<br />

survey for pest animals (based on surveys control threats).<br />

Outplant native plants. Address wildfire through hazardous<br />

fuels treatment, maintaining fuelbreaks, developing fire<br />

prevention program.<br />

500 acres. Remove ranch debris. Build <strong>and</strong> maintain fence,<br />

eradicate/control invasive plants, <strong>and</strong> remove pest animals.<br />

Conduct annual invasive plant survey; conduct survey for<br />

pest animals (based on surveys control threats). Outplant<br />

T&E plants <strong>and</strong> build site specific fencing for these plants.<br />

500 T&E plants <strong>and</strong> 2,000 native plants provided annually<br />

for restoration. Develop native plant nursery at Mauna Loa<br />

field camp site, collect seeds <strong>and</strong> cuttings, develop (in<br />

7 years) staff, volunteer, <strong>and</strong> partnering programs.<br />

LPP completed within one year. Identify habitats to support<br />

focal species; develop protection strategies; work proactively<br />

with partners, neighbors, <strong>and</strong> private l<strong>and</strong>owners where<br />

appropriate to meet conservation goals <strong>and</strong> develop specific<br />

project proposals for l<strong>and</strong> acquisition, cooperative<br />

agreements, <strong>and</strong>/or conservation easements as key<br />

conservation opportunities arise <strong>and</strong> willing parties are<br />

identified.<br />

Remove ranch debris. Build <strong>and</strong> maintain fence <strong>and</strong> develop<br />

site specific access protocols to limit human disturbance to<br />

habitat. Eradicate/control invasive plants, <strong>and</strong> remove pest<br />

animals. Conduct survey for pest animals (based on surveys<br />

control threats). Inventory <strong>and</strong> map communities <strong>and</strong><br />

support additional investigations <strong>and</strong> research.<br />

7,000 acres. Remove pest animals, eradicate/control invasive<br />

plants, build site-specific fencing to protect T&E plant<br />

populations <strong>and</strong> Carex sp. bogs. Conduct annual invasive<br />

plant survey; conduct survey for pest animals (based on<br />

surveys control threats). Inventory vegetation, complete<br />

Wilderness Study.<br />

Executive Summary

Executive Summary<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Objectives CCP Action<br />

3.2: Protect <strong>and</strong> Maintain Native<br />

Montane Wet ‘Ōhi‘a Forest<br />

(4,000-5,000 ft elevation) at HFU<br />

3.3: Restore, Protect, <strong>and</strong> Maintain<br />

Native Montane Wet Koa/‘Ōhi‘a<br />

Forest<br />

(5,000-6,000 ft elevation) at HFU<br />

3.4: Protect <strong>and</strong> Maintain Native<br />

Montane Mesic Koa Forest (6,000-<br />

6,600 ft elevation) at HFU<br />

3.5: Restore/Reforest Native Montane<br />

Mesic Koa Forest<br />

(6,000-6,600 ft elevation) at HFU<br />

3.6: Maintain <strong>and</strong> Enhance<br />

Propagation <strong>and</strong> Outplanting Program<br />

at HFU<br />

4.1: Protect <strong>and</strong> Maintain Streams <strong>and</strong><br />

Stream Corridors at HFU<br />

4.2: Protect <strong>and</strong> Maintain<br />

Semipermanent Natural Ponds at HFU<br />

4.3: Protect <strong>and</strong> Maintain Carex Bogs<br />

within the Montane Wet ‘Ōhi‘a/Uluhe<br />

Forest at HFU<br />

8,200 acres. Maintain existing fence (units 1-8), build <strong>and</strong><br />

maintain fence. Eradicate/control invasive plants <strong>and</strong> remove<br />

pest animals. Conduct annual invasive plant survey; conduct<br />

survey for pest animals (based on surveys control threats).<br />

Outplant native overstory koa <strong>and</strong> ‘ōhi‘a, T&E plants, <strong>and</strong><br />

common understory plants. Build site specific fencing for<br />

T&E plants. Complete Wilderness Study.<br />

5,000 acres. Maintain existing fence, build <strong>and</strong> maintain<br />

fence along Middle Maulua tract boundary (unit 9).<br />

Eradicate/control invasive plants <strong>and</strong> remove pest animals.<br />

Conduct annual invasive plant survey; conduct survey for<br />

pest animals (based on surveys control threats, particularly<br />

Vespula sp. ). Outplant T&E plants <strong>and</strong> build site-specific<br />

fencing to protect T&E plant populations.<br />

3,500 acres. Maintain existing fence. Eradicate/control<br />

invasive plants <strong>and</strong> remove pest animals. Conduct annual<br />

invasive plant survey; conduct survey for pest animals (based<br />

on surveys control threats, particularly Vespula sp. ).<br />

Outplant T&E plants <strong>and</strong> build site-specific fencing to<br />

protect T&E plant populations. Address wildfire through<br />

hazardous fuels treatment, maintaining fuelbreaks,<br />

developing fire prevention program.<br />

2,500 acres. Maintain fence. Eradicate/control invasive<br />

plants <strong>and</strong> remove pest animals. Conduct annual invasive<br />

plant survey; conduct survey for pest animals (based on<br />

surveys control threats). Outplant 300 koa per acre, use<br />

excluder devices to deter turkeys on koa seedlings, outplant<br />

native understory species <strong>and</strong> ‘ōhi‘a at 150 per acres,<br />

outplant 100-300 T&E plants <strong>and</strong> build site-specific fencing<br />

to protect these plants. Address wildfire through hazardous<br />

fuels treatment, maintaining fuelbreaks, developing fire<br />

prevention program.<br />

<strong>Plan</strong>t 10,000 koa per year for 5 years: 5,000 per year for the<br />

next 10 years, 8-10,000 natives <strong>and</strong> 300-1,200 T&E<br />

plantings per year. Exp<strong>and</strong> native plant nursery at Mauna<br />

Kea administration site, collect seeds <strong>and</strong> cuttings, outplant,<br />

<strong>and</strong> develop partnerships to assist with propagation program.<br />

Maintain fencing. Eradicate/control invasive plants. Conduct<br />

annual invasive plant survey; conduct survey for pest<br />

animals (based on surveys control threats). Inventory streams<br />

<strong>and</strong> stream corridors.<br />

Maintain fencing, conduct survey for pest animals (based on<br />

surveys control threats).<br />

Install fencing to protect bogs, conduct survey for pest<br />

animals (based on surveys control threats), survey extent <strong>and</strong><br />

number of bogs.

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Objectives CCP Action<br />

5.1: Maintain Managed Grassl<strong>and</strong> for<br />

Foraging Nēnē at HFU<br />

5.2: Maintain Grassl<strong>and</strong> Habitats for<br />

Nēnē Nesting at HFU<br />

6.1: Conduct High-Priority Inventory<br />

<strong>and</strong> Monitoring (Survey) Activities that<br />

Evaluate Resource Management <strong>and</strong><br />

Public-Use Activities to Facilitate<br />

Adaptive Management<br />

6.2: Conduct High-Priority Research<br />

Projects that Provide the Best Science<br />

for Habitat <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Management<br />

On <strong>and</strong> Off the Refuge<br />

6.3: Conduct Scientific Assessments to<br />

Provide Baseline Information to<br />

Exp<strong>and</strong> Knowledge Regarding the<br />

Status of Refuge Resources to Better<br />

Inform Resource Management<br />

Decisions<br />

7.1: Establish Compatible <strong>Wildlife</strong><br />

Observation <strong>and</strong> Photography<br />

Opportunities<br />

7.2: Promote <strong>and</strong> Enhance Volunteer<br />

Program<br />

7.3: Support Existing Outside<br />

Programs for On <strong>and</strong> Off Site<br />

Environmental Education <strong>and</strong> Develop<br />

Interpretive Opportunities<br />

7.4: Enhance Outreach Targeting<br />

Local Communities to Promote<br />

Appreciation of <strong>and</strong> Generate Support<br />

for the KFU<br />

65 acres. Maintain fuel breaks <strong>and</strong> fence corridors, build <strong>and</strong><br />

maintain fence. Eradicate/control invasive plants. Conduct<br />

survey for pest animals (based on surveys control threats).<br />

15 acres. Maintain fence <strong>and</strong> build predator proof fence on<br />

15-acre grassl<strong>and</strong> breeding site away from administrative site<br />

at Pua ‘Ākala tract. Eradicate/control invasive plants <strong>and</strong><br />

remove pest animals. Conduct survey for pest animals (based<br />

on surveys control threats).<br />

An initial list of survey <strong>and</strong> monitoring activities have been<br />

identified <strong>and</strong> include examples such as monitoring nesting<br />

density <strong>and</strong> success of nēnē, inventorying all endemic<br />

species, instituting early detection <strong>and</strong> rapid response<br />

monitoring for threat management, monitoring plant <strong>and</strong><br />

animal diseases, <strong>and</strong> others.<br />

An initial list of research projects have been identified <strong>and</strong><br />

include examples such as investigating <strong>and</strong> monitoring<br />

endangered plant propagation <strong>and</strong> outplanting, research on<br />

arthropod abundance, researching demography, life-history,<br />

carrying capacity, <strong>and</strong> competition for native forest birds,<br />

<strong>and</strong> others.<br />

An initial list of scientific assessments have been identified<br />

<strong>and</strong> include examples such as determining ecological<br />

parameters for ‘ōpe‘ape‘a, determining the role of predators<br />

in native flora <strong>and</strong> fauna abundance, assessing global climate<br />

change impacts on the Refuge, <strong>and</strong> others.<br />

Develop Upper Maulua Tract interpretive trail (0.3-0.5 mile)<br />

<strong>and</strong> parking area. Work with Friends of Hakalau Forest to<br />

develop brochure.<br />

Maintain volunteer program <strong>and</strong> current 35-40 service<br />

weekends at HFU, develop seasonal volunteer program to<br />

supplement staffing <strong>and</strong> weekend programs, develop KFU<br />

volunteer program similar to HFU.<br />

Increase environmental education <strong>and</strong> interpretive programs<br />

(via coordinating more with County, State, <strong>and</strong> nongovernmental<br />

organizations <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ing interpretive<br />

programs relative to cultural resources/historic sites) to<br />

include 168 participants annually. Continue interpretive<br />

walks offered during annual Refuge open house.<br />

Work with existing partners to promote awareness <strong>and</strong><br />

appreciation. Develop <strong>and</strong> cultivate new partners <strong>and</strong><br />

outreach efforts.<br />

Executive Summary

Executive Summary<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Objectives CCP Action<br />

8.1: Increase Identification,<br />

Monitoring, Protection, <strong>and</strong><br />

Restoration of all Cultural Resources<br />

<strong>and</strong> Historic Sites, while Increasing<br />

Staff <strong>and</strong> Public Support <strong>and</strong><br />

Appreciation<br />

Evaluate known/potential Refuge cultural resources <strong>and</strong><br />

historic sites, develop guidelines for cultural activities,<br />

identify cultural practitioners to develop underst<strong>and</strong>ing of<br />

cultural/historic sites at the Refuge, develop interpretive<br />

programming <strong>and</strong> products relative to cultural <strong>and</strong> historic<br />

sites in partnership with Native Hawaiian groups; conduct<br />

comprehensive cultural resources investigation of both units.<br />

Implementation of the <strong>Plan</strong>:<br />

Over the next 15 years, Refuge staff will be implementing these various strategies as funding <strong>and</strong><br />

staffing allow. We look forward to continue working with our partners <strong>and</strong> the public as we<br />

strive to attain our goals <strong>and</strong> vision for these unique Hawaiian rainforests <strong>and</strong> the numerous<br />

native plants <strong>and</strong> animals that depend upon them for their survival.

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background ..................................................................................... 1-1<br />

1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1-1<br />

1.2 Purpose <strong>and</strong> Need for the CCP ........................................................................................... 1-1<br />

1.3 Content <strong>and</strong> Scope of the CCP ........................................................................................... 1-2<br />

1.4 <strong>Plan</strong>ning <strong>and</strong> Management Guidance ................................................................................ 1-2<br />

1.4.1 U.S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service Mission ....................................................................... 1-2<br />

1.4.2 National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System ................................................................................. 1-9<br />

1.4.3 National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System Administration Act ............................................... 1-10<br />

1.5 Relationship to Previous <strong>and</strong> Future Refuge <strong>Plan</strong>s ........................................................ 1-11<br />

1.5.1 Previous <strong>Plan</strong>s ............................................................................................................ 1-11<br />

1.5.2 Future <strong>Plan</strong>ning .......................................................................................................... 1-12<br />

1.6 Refuge Establishment <strong>and</strong> Purposes ................................................................................ 1-12<br />

1.6.1 Hakalau Forest Unit Purposes .................................................................................. 1-13<br />

1.6.2 Kona Forest Unit Purposes ...................................................................................... 1-13<br />

1.7 Relationship to Ecosystem Management Goals or <strong>Plan</strong>s ............................................... 1-13<br />

1.7.1 L<strong>and</strong>scape Level Initiatives ..................................................................................... 1-13<br />

1.7.2 Statewide <strong>Plan</strong>s (including Threatened <strong>and</strong> Endangered Species<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong>s) ...................................................................................................... 1-18<br />

1.8 <strong>Plan</strong>ning <strong>and</strong> Issue Identification ..................................................................................... 1-27<br />

1.8.1 Public Scoping Sessions ............................................................................................. 1-27<br />

1.8.2 Interagency Scoping ................................................................................................... 1-29<br />

1.8.3 Forest Bird Workshop ................................................................................................ 1-30<br />

1.9 Refuge Vision ..................................................................................................................... 1-32<br />

1.10 Refuge Goals ...................................................................................................................... 1-33<br />

1.11 References .......................................................................................................................... 1-34<br />

Chapter 2. Refuge Management Direction .................................................................................... 2-1<br />

2.1 Considerations in the Design of the CCP........................................................................... 2-1<br />

2.2 General Guidelines .............................................................................................................. 2-1<br />

2.3 Goals, Objectives, <strong>and</strong> Strategies ..................................................................................... 2-12<br />

2.3.1 Kona Forest Unit ........................................................................................................ 2-13<br />

2.3.1.1 Goal 1: Protect, maintain, <strong>and</strong> restore subtropical rainforest community<br />

on the leeward slope of Mauna Loa as habitat for all life-history needs<br />

to promote the recovery of endangered species (e.g., forest birds,<br />

‘ōpe‘ape‘a, plants, <strong>and</strong> invertebrates). ............................................................... 2-13<br />

2.3.1.2 Goal 2: Protect <strong>and</strong> maintain lava tube <strong>and</strong> lava tube skylight habitat<br />

throughout the Kona Forest Unit, with special emphasis on their unique<br />

<strong>and</strong> endemic flora <strong>and</strong> fauna. ............................................................................. 2-19<br />

2.3.2 Hakalau Forest Unit .................................................................................................... 2-20<br />

2.3.2.1 Goal 3: Protect, maintain, <strong>and</strong> restore subtropical rainforest community<br />

on the windward slope of Mauna Kea as habitat for all life-history needs<br />

of endangered species (e.g., forest birds, ‘ōpe‘ape‘a, plants, <strong>and</strong><br />

invertebrates) ..................................................................................................... 2-20<br />

Table of Contents i

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

2.3.2.2 Goal 4: Protect <strong>and</strong> maintain wetl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> aquatic habitats (e.g., streams<br />

<strong>and</strong> their associated riparian corridors, ponds, <strong>and</strong> bogs) on the Hakalau<br />

Forest Unit. ........................................................................................................ 2-28<br />

2.3.2.3 Goal 5: Protect <strong>and</strong> maintain grassl<strong>and</strong> habitat to support nēnē population<br />

recovery ............................................................................................................. 2-30<br />

2.3.3 Both Hakalau Forest <strong>and</strong> Kona Forest Units .............................................................. 2-33<br />

2.3.3.1 Goal 6: Collect scientific information (inventories, monitoring, research,<br />

assessments) necessary to support adaptive management decisions on<br />

both units of Hakalau Forest NWR. .................................................................. 2-33<br />

2.3.3.2 Goal 7: Visitors, with a special emphasis on experience gained through<br />

volunteer work groups <strong>and</strong> local residents, underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>/or value<br />

the native forest environment <strong>and</strong> management practices at Hakalau<br />

Forest NWR. ...................................................................................................... 2-37<br />

2.3.3.3 Goal 8: Protect <strong>and</strong> manage cultural resources <strong>and</strong> historic sites for their<br />

educational <strong>and</strong> cultural values for the benefit of present <strong>and</strong> future<br />

generations of Refuge users <strong>and</strong> communities. ................................................. 2-40<br />

2.4 References ........................................................................................................................... 2-42<br />

Chapter 3. Physical Environment .................................................................................................. 3-1<br />

3.1 Climate .................................................................................................................................. 3-1<br />

3.1.1 Hakalau Forest Unit Climate ........................................................................................ 3-2<br />

3.1.2 Kona Forest Unit Climate ............................................................................................. 3-3<br />

3.2 Geology <strong>and</strong> Soils ................................................................................................................. 3-4<br />

3.2.1 Hakalau Forest Unit Geology <strong>and</strong> Soils ....................................................................... 3-4<br />

3.2.2 Kona Forest Unit Geology <strong>and</strong> Soils ............................................................................ 3-6<br />

3.3 Hydrology ............................................................................................................................. 3-8<br />

3.3.1 Hakalau Forest Unit Hydrology ................................................................................. 3-10<br />

3.3.2 Kona Forest Unit Hydrology ...................................................................................... 3-11<br />

3.4 Topography ........................................................................................................................ 3-11<br />

3.4.1 Hakalau Forest Unit Topography ............................................................................... 3-12<br />

3.4.2 Kona Forest Unit Topography .................................................................................... 3-12<br />

3.5 Environmental Contaminants .......................................................................................... 3-12<br />

3.5.1 Hakalau Forest Unit Contaminants ............................................................................ 3-12<br />

3.5.2 Kona Forest Unit Contaminants ................................................................................. 3-13<br />

3.6 L<strong>and</strong> Use ............................................................................................................................. 3-13<br />

3.6.1 Local L<strong>and</strong> Use Designations: Hakalau Forest Unit ................................................. 3-13<br />

3.6.2 Local L<strong>and</strong> Use Designations: Kona Forest Unit ...................................................... 3-15<br />

3.7 Global Climate Change ...................................................................................................... 3-17<br />

3.8 References ........................................................................................................................... 3-20<br />

Chapter 4. Refuge Biology <strong>and</strong> Habitats ...................................................................................... 4-1<br />

4.1 Biological Integrity Analysis ............................................................................................... 4-1<br />

4.2 <strong>Conservation</strong> Target Selection <strong>and</strong> Analysis ..................................................................... 4-2<br />

4.3 Habitats ................................................................................................................................. 4-5<br />

4.3.1 Hakalau Forest Unit ...................................................................................................... 4-5<br />

4.3.2 Kona Forest Unit ........................................................................................................ 4-10<br />

4.4 Endangered Hawaiian Forest Birds ................................................................................. 4-14<br />

4.4.1 ‘Akiapōlā‘au ............................................................................................................... 4-16<br />

ii Table of Contents

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

4.4.2 Hawai‘i ‘Ākepa .......................................................................................................... 4-21<br />

4.4.3 Hawai‘i Creeper .......................................................................................................... 4-24<br />

4.4.4 ‘Ō‘ū ............................................................................................................................ 4-25<br />

4.4.5 ‘Ālalā .......................................................................................................................... 4-27<br />

4.4.6 ‘Io ............................................................................................................................... 4-29<br />

4.5 Other Native Hawaiian Forest Birds ............................................................................... 4-31<br />

4.5.1 ‘I‘iwi ........................................................................................................................... 4-32<br />

4.5.2 Common ‘Amakihi ..................................................................................................... 4-33<br />

4.5.3 ‘Apanane..................................................................................................................... 4-35<br />

4.5.4 Hawai‘i ‘Elepaio ......................................................................................................... 4-36<br />

4.5.5 ‘Ōma‘o ........................................................................................................................ 4-38<br />

4.5.6 Pueo ............................................................................................................................ 4-39<br />

4.6 Endangered Hawaiian Waterbirds .................................................................................. 4-40<br />

4.6.1 Nēnē ............................................................................................................................ 4-41<br />

4.6.2 Koloa Maoli ................................................................................................................ 4-42<br />

4.6.3 ‘Alae ke‘oke‘o ............................................................................................................ 4-43<br />

4.7 Endangered Mammal ........................................................................................................ 4-44<br />

4.7.1 ‘Ōpe‘ape‘a .................................................................................................................. 4-44<br />

4.8 Native Hawaiian Invertebrates ......................................................................................... 4-45<br />

4.8.1 Picture-wing Flies ....................................................................................................... 4-46<br />

4.8.2 Koa Bug ...................................................................................................................... 4-47<br />

4.8.3 Cave Invertebrates ...................................................................................................... 4-48<br />

4.8.4 Arthropods .................................................................................................................. 4-49<br />

4.8.5 Mollusks ..................................................................................................................... 4-56<br />

4.9 Endangered <strong>and</strong> Threatened <strong>Plan</strong>ts ................................................................................. 4-57<br />

4.9.1 Asplenium peruvianum var. insulare .......................................................................... 4-58<br />

4.9.2 Clermontia lindseyana ................................................................................................ 4-59<br />

4.9.3 Clermontia peleana .................................................................................................... 4-60<br />

4.9.4 Clermontia pyrularia .................................................................................................. 4-61<br />

4.9.5 Hāhā ............................................................................................................................ 4-62<br />

4.9.6 ‘Aku‘aku ..................................................................................................................... 4-62<br />

4.9.7 Cyanea shipmanii ....................................................................................................... 4-63<br />

4.9.8 Cyanea stictophylla .................................................................................................... 4-64<br />

4.9.9 Ha‘iwale ..................................................................................................................... 4-65<br />

4.9.10 ‘Aiea ......................................................................................................................... 4-65<br />

4.9.11 Phyllostegia floribunda ............................................................................................ 4-66<br />

4.9.12 Kīponapona ............................................................................................................... 4-67<br />

4.9.13 Phyllostegia velutina ................................................................................................ 4-68<br />

4.9.14 Po‘e ........................................................................................................................... 4-68<br />

4.9.15 ‘Ānunu ...................................................................................................................... 4-69<br />

4.9.16 Silene hawaiiensis .................................................................................................... 4-70<br />

4.10 Other Native <strong>Plan</strong>ts ......................................................................................................... 4-70<br />

4.10.1 Koa ........................................................................................................................... 4-76<br />

4.10.2‘Ōhi‘a .......................................................................................................................... 4-78<br />

4.10.3 Māmane ..................................................................................................................... 4-80<br />

4.11 Cave Resources ................................................................................................................ 4-80<br />

4.12 Threats .............................................................................................................................. 4-82<br />

4.12.1 Introduced Forest Birds ............................................................................................ 4-83<br />

Table of Contents iii

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

4.12.2 Introduced Game Birds ............................................................................................. 4-85<br />

4.12.3 Introduced Mammals ................................................................................................ 4-85<br />

4.12.4 Introduced Reptiles <strong>and</strong> Amphibians ....................................................................... 4-93<br />

4.12.5 Introduced Arthropods .............................................................................................. 4-94<br />

4.12.6 Introduced <strong>Plan</strong>ts ...................................................................................................... 4-96<br />

4.12.7 Introduced Mollusks ............................................................................................... 4-109<br />

4.13 Special Designation Areas ............................................................................................ 4-109<br />

4.14 References ....................................................................................................................... 4-109<br />

Chapter 5. Social <strong>and</strong> Economic Environment ............................................................................. 5-1<br />

5.1 Refuge Infrastructure <strong>and</strong> Administrative Facilities ....................................................... 5-1<br />

5.1.1 Hakalau Forest Unit ...................................................................................................... 5-1<br />

5.1.2 Kona Forest Unit .......................................................................................................... 5-2<br />

5.1.3 Hilo Administrative Office ........................................................................................... 5-2<br />

5.2 Public Use Overview ............................................................................................................ 5-2<br />

5.2.1 Federal, State, <strong>and</strong> County Recreational Parks ............................................................ 5-2<br />

5.2.2 <strong>Wildlife</strong> Observation <strong>and</strong> Environmental Education .................................................. 5-11<br />

5.2.3 Camping ..................................................................................................................... 5-13<br />

5.2.4 Hiking ......................................................................................................................... 5-13<br />

5.2.5 Hunting ....................................................................................................................... 5-13<br />

5.2.6 Refuge Public Use Opportunities ............................................................................... 5-14<br />

5.2.7 Recreational Trends <strong>and</strong> Dem<strong>and</strong>s ............................................................................. 5-17<br />

5.2.8 Impact of Illegal Uses ................................................................................................ 5-17<br />

5.2.9 Historic/Cultural Sites ................................................................................................ 5-17<br />

5.2.10 Special Designation Areas ......................................................................................... 5-20<br />

5.3 Social <strong>and</strong> Economic Conditions ...................................................................................... 5-20<br />

5.3.1 Population ................................................................................................................... 5-20<br />

5.3.2 Housing ...................................................................................................................... 5-21<br />

5.3.3 Education .................................................................................................................... 5-21<br />

5.3.4 Employment <strong>and</strong> Income ............................................................................................ 5-22<br />

5.3.5 Economy ..................................................................................................................... 5-23<br />

5.3.6 Refuge Contribution ................................................................................................... 5-25<br />

5.4 References ........................................................................................................................... 5-25<br />

Tables<br />

Table 2-1 Summary of CCP Actions. ............................................................................................... 2-9<br />

Table 3-1 Average Monthly Rainfall (inches) at the Kona Forest Unit, April 1995-<br />

November 1998. .............................................................................................................. 3-3<br />

Table 3-2 Soil types Found Within the Hakalau Forest Unit <strong>and</strong> Key Characteristics. .................... 3-6<br />

Table 3-3 Soil Types Found Within the Kona Forest Unit <strong>and</strong> Key Characteristics. ....................... 3-8<br />

Table 3-4 Streams <strong>and</strong> Tributaries on the Hakalau Forest Unit. ..................................................... 3-10<br />

Table 4-1 Refuge <strong>Conservation</strong> Targets. .......................................................................................... 4-3<br />

Table 4-2 Endangered <strong>and</strong> Rare Native Invertebrate Species Occurring or Potentially<br />

Occurring on Hakalau Forest NWR. ............................................................................. 4-46<br />

Table 4-3 Endemic Arthropods in Three Cave Systems at the KFU. ............................................. 4-49<br />

Table 4-4 Arthropods Occurring at the HFU <strong>and</strong> KFU. ................................................................. 4-53<br />

Table 4-5 Endangered <strong>and</strong> Threatened <strong>Plan</strong>t Species that Occur (or Potentially Occur)<br />

at Hakalau Forest NWR. ............................................................................................... 4-58<br />

iv Table of Contents

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Table 4-6 Native Hawaiian <strong>Plan</strong>ts Found on the Units of Hakalau Forest NWR. .......................... 4-71<br />

Table 4-7 Total Native Seedlings Outplanted at the HFU 1987-2007. ........................................... 4-76<br />

Table 4-8 Introduced Forest Birds Present at HFU <strong>and</strong> KFU. ........................................................ 4-84<br />

Table 4-9 Introduced Game birds Present at HFU <strong>and</strong> KFU. ......................................................... 4-85<br />

Table 4-10 List of Invasive <strong>Plan</strong>t Species Known to Currently Occur at Hakalau Forest NWR. ... 4-98<br />

Table 5-1 Legend ID <strong>and</strong> Facility Name for the Vicinity Recreation Map. ..................................... 5-9<br />

Table 5-2 FY 2010 Visitation at the Hakalau Forest Unit. ............................................................. 5-16<br />

Table 5-3 Population Figures for Selected Areas. .......................................................................... 5-21<br />

Table 5-4 Hawai‘i County Industry Job Counts <strong>and</strong> Average Annual Wages. .............................. 5-23<br />

Figures<br />

Figure 1-1 Refuge Vicinity ................................................................................................................ 1-3<br />

Figure 1-2 HFU Location ................................................................................................................... 1-5<br />

Figure 1-3 KFU Location ................................................................................................................... 1-7<br />

Figure 2-1 HFU CCP Management ................................................................................................... 2-5<br />

Figure 2-2 KFU CCP Management ................................................................................................... 2-7<br />

Figure 3-1 Soil Map of the Hakalau Forest Unit ............................................................................... 3-5<br />

Figure 3-2 Soil Map of the Kona Forest Unit .................................................................................... 3-7<br />

Figure 3-3 L<strong>and</strong> Use District Boundaries – Hakalau Forest Unit .................................................... 3-15<br />

Figure 3-4 L<strong>and</strong> Use District Boundaries – Kona Forest Unit ........................................................ 3-16<br />

Figure 4-1 Native Forest Bird Trends on Hawai‘i Isl<strong>and</strong> .................................................................. 4-2<br />

Figure 4-2 HFU Vegetation Type ...................................................................................................... 4-7<br />

Figure 4-3 KFU Vegetation Type .................................................................................................... 4-11<br />

Figure 4-4 North Hāmākua Study Area ........................................................................................... 4-15<br />

Figure 4-5 Annual Forest Bird Survey Transects ............................................................................ 4-17<br />

Figure 4-6 Central Windward Study Area ....................................................................................... 4-20<br />

Figure 4-7 Hakalau Forest Unit 2007 Weed Survey Map ............................................................. 4-101<br />

Figure 5-1 Hakalau Forest Volunteer Cabin ...................................................................................... 5-1<br />

Figure 5-2 HFU Administrative Facilities <strong>and</strong> Infrastructure ............................................................ 5-3<br />

Figure 5-3 KFU Administrative Facilities <strong>and</strong> Infrastructure ............................................................ 5-5<br />

Figure 5-4 Recreation Opportunities on Hawai‘i Isl<strong>and</strong> .................................................................... 5-7<br />

Appendices<br />

Appendix A. Species Lists for Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge ....................................... A-1<br />

Appendix B. Appropriate Uses <strong>and</strong> Compatibility Determinations ................................................ B-1<br />

Appendix C. <strong>Plan</strong> Implementation ................................................................................................... C-1<br />

Appendix D. Wilderness Review for Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge ............................ D-1<br />

Appendix E. Forest Bird Workshop Report .................................................................................... E-1<br />

Appendix F. Biological Integrity, Diversity, <strong>and</strong> Environmental Health<br />

<strong>and</strong> Resources of Concern ..................................................................................... F-1<br />

Appendix G. Integrated Pest Management Program ........................................................................ G-1<br />

Appendix H. Statement of Compliance ........................................................................................... H-1<br />

Appendix I. Acronyms <strong>and</strong> Abbreviations ...................................................................................... I-1<br />

Appendix J. CCP Team Members ................................................................................................... J-1<br />

Appendix K. Summary of Public Involvement ................................................................................ K-1<br />

Appendix L. Summary of Past <strong>and</strong> Current Management ............................................................... L-1<br />

Table of Contents v

vi<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Note to Reviewers: Throughout the CCP document, all attempts have been made<br />

to use appropriate diacriticals related to the Native Hawaiian language<br />

(i.e., ‘okina <strong>and</strong> kahakō). However, places where diacriticals may not appear are<br />

in the maps, appendices, <strong>and</strong> references. Due to limitations of the Geospatial<br />

Information System (GIS) software used for the maps developed in the plan,<br />

diacriticals were unable to be used where place names or legend text appear. For<br />

items in the appendices, if documents were minutes or summaries of meetings or<br />

documents not created for the CCP that did not use diacriticals originally, the<br />

document was left as is. For references identified, if the title of the publication or<br />

original citation does not use diacriticals, references were left as is.

Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background<br />

Above: ‘Io/Robert Shallenberger<br />

Right: ‘Amakihi/Jack Jeffrey Photography<br />

Hakalau Forest Unit rainforest/Dick Wass

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background<br />

1.1 Introduction<br />

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge consists of the Hakalau Forest Unit <strong>and</strong> the Kona Forest<br />

Unit (Figure 1-1) collectively managed as the Big Isl<strong>and</strong> National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge Complex<br />

(Complex). The Hakalau Forest Unit (HFU) (Figure 1-2) was established in 1985 to protect <strong>and</strong><br />

manage endangered forest birds <strong>and</strong> their rainforest habitat. Located on the windward slope of<br />

Mauna Kea, Isl<strong>and</strong> of Hawai‘i, the 32,733 acre unit supports a diversity of native birds <strong>and</strong> plants.<br />

The Kona Forest Unit (KFU) (Figure 1-3) was set aside in 1997 to protect native forest birds <strong>and</strong> the<br />

‘alalā (Corvus hawaiiensis, Hawaiian crow). Located on the leeward slope of Mauna Loa, the<br />

5,300 acre KFU supports diverse native bird <strong>and</strong> plant species as well as the rare lava tube <strong>and</strong> lava<br />

tube skylight habitats.<br />

1.2 Purpose <strong>and</strong> Need for the CCP<br />

The purpose of the CCP is to provide the Complex, the National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System, the<br />

Service, partners, <strong>and</strong> citizens with a management plan for improving fish <strong>and</strong> wildlife habitat<br />

conditions <strong>and</strong> infrastructure for wildlife, staff, <strong>and</strong> public use on the Refuge over the next 15 years.<br />

An approved CCP will ensure that the Complex staff manages Hakalau Forest NWR to achieve<br />

Refuge purposes, vision, goals, <strong>and</strong> objectives to help fulfill the Refuge System mission.<br />

The CCP will provide reasonable, scientifically grounded guidance for managing <strong>and</strong> improving the<br />

Refuge’s forest, subterranean, riparian, aquatic, <strong>and</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong> habitats for the long-term conservation<br />

of native plants <strong>and</strong> animals. Appropriate actions for protecting <strong>and</strong> sustaining the biological <strong>and</strong><br />

cultural features of forest communities; endangered species populations <strong>and</strong> habitats; <strong>and</strong> threatened<br />

or rare species have been identified. The CCP also promotes priority public use activities on the<br />

Refuge including wildlife observation, photography, environmental education, <strong>and</strong> interpretation.<br />

The CCP is needed for a variety of reasons. Primary among these is the need to conserve the<br />

Refuge’s forest, subterranean, riparian, aquatic, <strong>and</strong> grassl<strong>and</strong> habitats that are in various stages of<br />

(1) degradation by pest plants <strong>and</strong> animals (most notably ungulates <strong>and</strong> invasive plants), (2) recovery<br />

from cattle grazing activities by past owners, <strong>and</strong> (3) restoration by Refuge staff. The CCP is needed<br />

to address the Refuge’s contributions to aid in the recovery of listed species, <strong>and</strong> assess <strong>and</strong> possibly<br />

mitigate potential impacts of global climate change. The staff also needs to effectively work with<br />

current partners such as the Hawai‘i Division of Forestry <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> (DOFAW), the U.S.<br />

Geological Survey-Biological Resources Discipline (USGS-BRD), the U.S. Forest Service (USFS),<br />

the Department of Hawaiian Home L<strong>and</strong>s (DHHL), <strong>and</strong> the National Park Service (NPS). The<br />

Refuge also needs to seek new partnerships to restore habitats, improve the volunteer program, <strong>and</strong><br />

identify to what extent improvements or alterations should be made to existing visitor programs. In<br />

addition, the Refuge will continue to work with the Friends of Hakalau Forest on various Refuge<br />

programs, community outreach, <strong>and</strong> Refuge management needs. These activities will allow the<br />

Refuge staff to ensure the biological integrity, diversity, <strong>and</strong> environmental health of the units are<br />

restored or maintained.<br />

Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background 1-1

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

1.3 Content <strong>and</strong> Scope of the CCP<br />

This CCP provides guidance for management of Refuge habitats <strong>and</strong> wildlife <strong>and</strong> administration of<br />

public uses on Refuge l<strong>and</strong>s. The Hakalau Forest NWR CCP is also intended to comply with the<br />

requirements set forth in the National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System Administration Act of 1966<br />

(Administration Act), as amended by the National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge Improvement Act of 1997<br />

(16 U.S.C. 668dd-668ee) <strong>and</strong> the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), as amended<br />

(42 U.S.C. 4321-4347). Information in the CCP includes:<br />

� An overall vision for the Refuge, each unit’s establishment history <strong>and</strong> purposes, <strong>and</strong> their role in<br />

the local ecosystem (Chapter 1);<br />

� Goals <strong>and</strong> objectives for specific conservation targets <strong>and</strong> public use programs, as well as<br />

strategies for achieving the objectives (Chapter 2);<br />

� A description of the physical environment of the Refuge (Chapter 3);<br />

� A description of the conservation targets, their condition <strong>and</strong> trends on the Refuge <strong>and</strong> within the<br />

local ecosystem, a presentation of the key desired ecological conditions for sustaining the targets,<br />

<strong>and</strong> a short analysis of the threats to each conservation target (Chapter 4);<br />

� An overview of the Refuge’s public use programs <strong>and</strong> facilities, a list of desired future conditions<br />

for each program, <strong>and</strong> other management considerations (Chapter 5);<br />

� A list of resident species (both native <strong>and</strong> nonnative) known from the Refuge (Appendix A);<br />

� Evaluations of existing <strong>and</strong> proposed appropriate public <strong>and</strong> economic uses for compatibility<br />

with the Refuge’s purposes (Appendix B);<br />

� An outline of the projects, staff, <strong>and</strong> facilities needed to support the CCP (Appendix C);<br />

� A review for wilderness designation (Appendix D);<br />

� Summary of a workshop held for implementing recovery for endangered forest birds<br />

(Appendix E);<br />

� A Biological Integrity, Diversity, <strong>and</strong> Environmental Health Table (Appendix F);<br />

� Integrated Pest Management Program (Appendix G);<br />

� Statement of Compliance for CCP (Appendix H);<br />

� List of acronyms (Appendix I);<br />

� A list of CCP Team Members (Appendix J);<br />

� A summary of public involvement (Appendix K); <strong>and</strong><br />

� A summary of past <strong>and</strong> current management (Appendix L).<br />

1.4 <strong>Plan</strong>ning <strong>and</strong> Management Guidance<br />

1.4.1 U. S. <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service Mission<br />

The mission of the Service is “working with others, to conserve, protect <strong>and</strong> enhance fish <strong>and</strong><br />

wildlife <strong>and</strong> their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people.” National natural<br />

resources entrusted to the Service for conservation <strong>and</strong> protection include migratory birds,<br />

endangered <strong>and</strong> threatened species, interjurisdictional fish, wetl<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> certain marine mammals.<br />

1-2 Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background

Figure 1-1.<br />

Refuge vicinity.<br />

Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> a Backgroun nd<br />

Hakalau H Forest National Wilddlife<br />

Refuge<br />

Comprehens sive Conservatiion<br />

<strong>Plan</strong><br />

1-3

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

To preserve the quality of this figure, this side was left blank intentionally.<br />

1-4 Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background

Figure 1-2.<br />

HFU location.<br />

Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> a Backgroun nd<br />

Hakalau H Forest National Wilddlife<br />

Refuge<br />

Comprehens sive Conservatiion<br />

<strong>Plan</strong><br />

1-5

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

To preserve the quality of this figure, this side was left blank intentionally.<br />

1-6 Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background

Figure 1-3.<br />

KFU location.<br />

Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> a Backgroun nd<br />

Hakalau H Forest National Wilddlife<br />

Refuge<br />

Comprehens sive Conservatiion<br />

<strong>Plan</strong><br />

1-7

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

To preserve the quality of this figure, this side was left blank intentionally.<br />

1-8 Chapter 1. Introduction <strong>and</strong> Background

Hakalau Forest National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge<br />

<strong>Comprehensive</strong> <strong>Conservation</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

The Service also manages national fish hatcheries, enforces Federal wildlife laws <strong>and</strong> international<br />

treaties on importing <strong>and</strong> exporting wildlife, assists with State/Territorial fish <strong>and</strong> wildlife programs,<br />

<strong>and</strong> helps other countries develop wildlife conservation programs. The Service is an agency within<br />

the Department of the Interior (DOI), <strong>and</strong> is the principal Federal agency responsible for conserving,<br />

protecting, <strong>and</strong> enhancing fish, wildlife, <strong>and</strong> plants <strong>and</strong> their habitats for the continuing benefit of the<br />

American people.<br />

1.4.2 National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System<br />

The Refuge System is the world’s largest network of public l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> waters set aside specifically<br />

for conserving wildlife <strong>and</strong> protecting ecosystems. From its inception in 1903, the Refuge System<br />

has grown to encompass 553 national wildlife refuges in all 50 States, 4 U.S. territories, <strong>and</strong> a<br />

number of unincorporated U.S. possessions, <strong>and</strong> waterfowl production areas in 10 States, covering<br />

more than 150 million acres of public l<strong>and</strong>s. It also manages four marine national monuments in the<br />

Pacific in coordination with the National Oceanic <strong>and</strong> Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) <strong>and</strong><br />

affected States/Territories. More than 40 million visitors annually fish, hunt, observe <strong>and</strong> photograph<br />

wildlife, or participate in environmental education <strong>and</strong> interpretive activities on these refuges.<br />

Refuges are guided by various Federal laws <strong>and</strong> Executive orders, Service policies, <strong>and</strong> international<br />

treaties. Fundamental are the mission <strong>and</strong> goals of the Refuge System <strong>and</strong> the designated purposes of<br />

the Refuge unit as described in establishing legislation, Executive orders, or other documents<br />

establishing, authorizing, or exp<strong>and</strong>ing a refuge.<br />

Key concepts <strong>and</strong> guidance for the Refuge System derive from the Administration Act, the Refuge<br />

Recreation Act of 1962 (16 U.S.C. 460k-460k-4), as amended, Title 50 of the Code of Federal<br />

Regulations, <strong>and</strong> the <strong>Fish</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Wildlife</strong> Service Manual. The Administration Act is implemented<br />

through regulations covering the Refuge System, published in Title 50, subchapter C of the Code of<br />

Federal Regulations. These regulations govern general administration of units of the Refuge System.<br />

This CCP complies with the Refuge Administration Act.<br />

1.4.2.1 National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System Mission <strong>and</strong> Goals<br />

The mission of the Refuge System is:<br />

“to administer a national network of l<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> waters for the conservation, management,<br />

<strong>and</strong> where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife, <strong>and</strong> plant resources <strong>and</strong> their<br />

habitats within the United States for the benefit of present <strong>and</strong> future generations of<br />

Americans” (National <strong>Wildlife</strong> Refuge System Administration Act of 1966, as<br />