Paratrechina longicornis - Biosecurity New Zealand

Paratrechina longicornis - Biosecurity New Zealand

Paratrechina longicornis - Biosecurity New Zealand

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Harris, R.; Abbott, K.<br />

(A) PEST INFORMATION<br />

A1. Classification<br />

Family: Formicidae<br />

Subfamily: Formicinae<br />

Tribe: Lasiini<br />

Genus: <strong>Paratrechina</strong><br />

Species: <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

A2. Common names<br />

Crazy ant (Smith 1965), long-horned ant, hairy ant (Naumann 1993), higenaga-ameiro-ari (www36), slender crazy ant<br />

(Deyrup et al. 2000).<br />

A3. Original name<br />

Formica <strong>longicornis</strong> Latreille<br />

A4. Synonyms or changes in combination or taxonomy<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> currens Motschoulsky, Formica gracilescens Nylander, Formica vagans Jerdon, Prenolepis <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(Latreille)<br />

Current subspecies: nominal plus <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> var. hagemanni Forel<br />

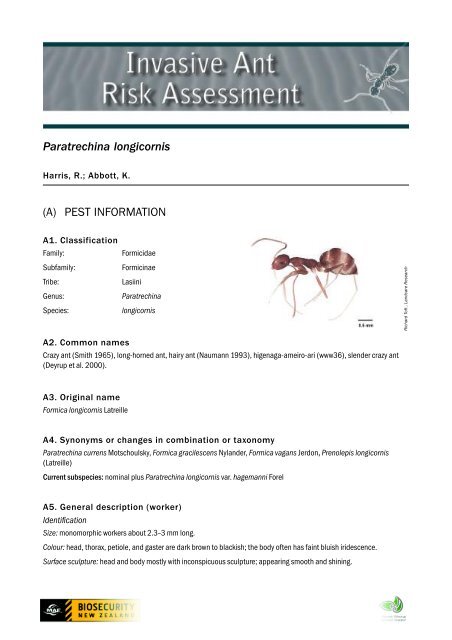

A5. General description (worker)<br />

Identification<br />

Size: monomorphic workers about 2.3–3 mm long.<br />

Colour: head, thorax, petiole, and gaster are dark brown to blackish; the body often has faint bluish iridescence.<br />

Surface sculpture: head and body mostly with inconspicuous sculpture; appearing smooth and shining.<br />

Richard Toft , Landcare Research

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Whole body has longish setae. Appears quite hairy. Hairs are light in colour grey to whitish.<br />

General description: antennae and legs extraordinarily long. Antenna slender, 12-segmented, without a club; scape at<br />

least 1.5 times as long as head including closed mandibles. Eyes large, maximum diameter 0.3 times head length;<br />

elliptical, strongly convex; placed close to the posterior border of the head. Head elongate; mandibles narrow, each with 5<br />

teeth. Clypeus without longitudinal carinae. Alitrunk slender, dorsum almost straight from anterior portion of pronotum to<br />

propodeal dorsum. Metanotal groove slightly incised. Propodeum without spines, posterodorsal border rounded;<br />

propodeal spiracles distinct. One node (petiole) present, wedge-shaped, with a broad base, and inclined forward. Dorsal<br />

surface of head, alitrunk and gaster with long, coarse, suberect to erect greyish or whitish setae. Propodeum without erect<br />

hairs. Hind femora and tibiae bearing suberect hairs with length almost equal to the width of the femora. Stinger lacking;<br />

acidopore present.<br />

Sources: www39<br />

Formal description: Creighton (1950)<br />

This species is morphologically distinctive and is one of the few <strong>Paratrechina</strong> species not consistently misidentified in<br />

collections.<br />

The crazy ant is extremely easy to identify from its rapid and erratic movements (wwwnew49). Identification can be<br />

confirmed with the aid of a hand lens through which the extremely long antennal scape, long legs, and erect setae are<br />

obvious.<br />

2

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Fig. 1: Images of <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong>; a) group of workers , b) dorsal view of worker showing long antennae (Source: S.D. Porter,<br />

USA-ARS).<br />

S.D. Porter, USA-ARS<br />

S.D. Porter, USA-ARS<br />

3

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

A6. Behavioural and biological characteristics<br />

A6.1 Feeding and foraging<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> foragers are opportunists (Andersen 1992). Workers are very fast moving, darting about in a<br />

jerky, haphazard fashion as if lacking a sense of direction (Smith 1965). They commonly form wide but thinly populous<br />

trails up to 0.5 m wide over walls and floors (Collingwood et al. 1997). Meier (1994) stated “trails form moving toward the<br />

nest only”, but this is not the case as they have been observed to forage to and from nests in thin (1–2 cm) trails (P. Lester,<br />

pers. comm.). They can forage long distances, up to 25 m from the nest (Jaffe 1993). They are very quick to discover food<br />

(Lee 2002) but are often displaced when dominant ants discover and then recruit to food (Banks & Williams 1989). In<br />

tropical locations they forage continuously (Meier 1994).<br />

Workers are omnivorous. They feed on live and dead insects, honeydew, fruits, and many household foods (Smith 1965).<br />

Honeydew is obtained by tending plant lice, mealy bugs and scales (Smith 1965; Rawat & Modi 1969; Farnsworth 1993).<br />

Crazy ants are especially fond of sweet food (Smith 1965). Foragers will also collect seeds (Smith 1965). Large prey<br />

items, e.g., lizards, are carried by a highly concerted group action (Trager 1984). They appear to show a strong preference<br />

for protein during summer, when they will refuse honey or sugar baits (Trager 1984). They can forage in the intertidal zone,<br />

where they “surf” if caught by a wave (Jaffe 1993). P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was also recorded on decaying rabbit carcasses in India,<br />

feeding on moist areas around the eyes, nose, mouth, and anal region during the early stage of decay and on dead flies,<br />

dead larvae, skin of carrion, etc., during later decay stages (Bharti & Singh 2003).<br />

A6.2 Colony characteristics<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> has polygyne colonies (Passera 1994), with nests containing up to 2000 workers and 40 queens<br />

(Mallis (1982, cited in Thompson 1990). Reproductives are produced throughout the year in warm climates but are more<br />

restricted ( ~ 5 months) in cooler climates, e.g., Gainsville, Florida (Trager 1984). Workers are probably sterile (Passera<br />

1994). Colonies occur in temporary nests (Andersen 2000), are highly mobile and will move if disturbed (Trager 1984).<br />

Crazy ants nest in diverse locations from dry to moist environments (www47). They tolerate nesting sites with relatively low<br />

humidity, such as gaps in walls, thatching and dry litter (Trager 1984). Outdoors, nests are primarily on the ground, often<br />

in wood, trash, and in mulch, but occasionally they occur aboreally in tree holes and leaf axils (Trager 1984; Way et al.<br />

1989). Indoors, nests are often in wall spaces and under stored items (Smith 1965; www47). Colonies and individuals<br />

from the same location appear to tolerate each other, but they behave aggressively towards individuals from distant sites<br />

(Lim et al. 2003). Queens do not appear to be responsible for this lack of intra-specific aggression; rather colony odours<br />

obtained through their diet influence their behaviour (Lim et al. 2003).<br />

Colonies nesting in sand at densities of over 1 nest/m 2 have been recorded in India (Jaffe 1993). At high tide, nests were<br />

underwater and probably protected from flooding by air trapped in their galleries.<br />

A7. Pest significance and description of range of impacts<br />

A7.1 Natural environment<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> appears to be a disturbance specialist and is seemingly absent from undisturbed natural habitat.<br />

Where it does occur in semi-natural vegetation it is often a minor component of the community (e.g., Andersen & Reichel<br />

1994; Clouse 1999; Santana-Reis & Santos 2001). Holway et al. (2002a) in their review of invasive ants did not consider<br />

P. <strong>longicornis</strong> significant. Mostly, it is not a competitive dominant (Levins et al. 1973; Torres 1984; Banks & Williams<br />

1989; Morrison 1996). On Nukunonu Island, Tokelau, in forested areas without the dominant invasive ant Anoplolepis<br />

gracilipe, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was the second most frequently caught ant in pitfall traps (Lester & Tavite 2004) and repelled<br />

other ants from baits (P. Lester, pers. comm.). This was a highly modified environment with few ant competitors. It was not<br />

sampled where A. gracilipes was present in forested areas, and was rare in urban areas that were dominated numerically<br />

by A. gracilipes (Lester & Tavite 2004).<br />

4

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

MacArthur and Wilson (1967) reported that on the Dry Tortugas, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was “an overwhelmingly abundant ant and<br />

has taken over nest sites that are normally occupied by other species in the rest of southern Florida: tree-boles, usually<br />

occupied by species of Camponotus and Crematogaster, which are absent from the Dry Tortugas; and open soil, normally<br />

occupied by crater nests of Dorymyrmex and Forelius, which genera are also absent from the Dry Tortugas”. The Dry<br />

Tortugas are the outermost of the Florida Keys, and are important ecologically as feeding and nesting grounds for turtles<br />

and frigate birds (Wetterer & O’Hara 2002). The islands are far from pristine and have many non-indigenous plants and<br />

animals. They are also highly disturbed, being periodically reshaped by hurricanes, which alter the size and even the<br />

number of keys.<br />

Wetterer and O’Hara (2002) reported P. <strong>longicornis</strong> to be common on four of the five islands in Florida Keys they surveyed.<br />

On Garden Key, Solenopsis geminata was the dominant ant on the ground, while P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was the most common ant<br />

in trees. On Loggerhead Key and Bush Key, Pheidole megacephala and P. <strong>longicornis</strong> were the most common ants.<br />

Although P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was common, Wetterer and O’Hara (2002) did not mention it, instead raising concern about the<br />

impacts of S. geminata and Ph. megacephala.<br />

The presence of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> at baits found first by another species was recorded during sequential checking of sugar<br />

water dishes and was used as a measure of species replacement by Clark et al. (1982) in the Galapagos. P. <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

replaced other ant species (including the little fire ant, Wasmannia auropunctata) at sugar-water baits in 68% of observations,<br />

indicating some potential competition for resources, but it did not stay as long at baits as W. auropunctata.<br />

Apparently, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> has limited ability to displace other ants. In Sao Paulo, Brazil, banana plantations where P.<br />

<strong>longicornis</strong> was present had fewer other ant species than those without P. <strong>longicornis</strong> (Fowler et al. 1994); however, this<br />

may have been caused not by the ability of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> to eliminate other ants, but because different management<br />

practices in some orchards eliminated competing species and allowed P. <strong>longicornis</strong> to establish. Only one study conclusively<br />

documented detrimental impacts on other ants and other invertebrates, other than at bait; this was in a highly<br />

artificial glass house environment —”Biosphere 2" (Wetterer et al. 1999). There, ants were sampled before and after the<br />

arrival of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>; the composition of the ant community changed markedly and those species remaining after P.<br />

<strong>longicornis</strong> became abundant were uncommon. Linepithema humile and Solenopsis xyloni both disappeared from the<br />

glass house environment and the only abundant invertebrates thriving in Biosphere 2 besides P. <strong>longicornis</strong> were<br />

homopterans and species with effective defences against ants (well-armoured isopods and millipedes) or tiny subterranean<br />

species not vulnerable to ant predation (mites, cryptic ants, and springtails).<br />

This species was also an abundant opportunist in disturbed habitat (mine site restoration trial plots) in Australia, but it<br />

was absent from bare ground dominated by Iridomyrmex and undisturbed vegetation (Andersen 1993).<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> interferes with seed dispersal of myrmecochorous plants by reducing dispersal distances and<br />

leaving seeds exposed on the soil surface (Ness & Bronstein 2004). No seeds were brought to the nest by this species<br />

during observations in Puerto Rico (Torres 1984).<br />

In some locations P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is restricted to human settlements, e.g., northern Australia (Andersen 2000), or is a<br />

relatively minor component of degraded habits or human-modified systems, e.g., the Canary Islands (Espadaler & Bernal<br />

2003), Sri Lanka (Way et al. 1989) and the Philippines (Way et al. 1998).<br />

A7.2 Horticulture<br />

Foragers are associated with honeydew-producing hemipterans (Smith 1965; Rawat & Modi 1969; Farnsworth 1993).<br />

Trails of foraging P. <strong>longicornis</strong> on plants in Biosphere 2 invariably led to homopterans (Wetterer et al. 1999). High<br />

densities of ants on plants were always found tending high densities of homopterans, such as the scale insects that<br />

heavily encrusted the trunks, branches, and leaves of many Piper trees, and mealybugs that covered the branches of<br />

many mangrove trees. Ants returning to their nests from these sources were bloated with liquid. Surveys of ants on Thalia<br />

geniculata L. leaves (common name alligator flag; a plant in the Marantaceae or arrowroot Family) demonstrated a strong<br />

positive association between ants and scale insects. On Tokelau, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is also associated with extra-floral<br />

5

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

nectaries of Morinda citrifolia and breadfruit trees, food sources which might assist them in reaching extreme abundances<br />

in some areas (K. Abbott, pers. obser.). They have also been observed tending black citrus aphid Toxoptera citricida,<br />

(Homoptera: Aphididae) (Michaud & Browning 1999). However, they may not have an important role in protecting<br />

homoptera from natural enemies: Dejean et al. (2000) found that the presence of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> did not increase<br />

populations of a maize pest in Cameroon, as did other ants present (including Pheidole megacephala).<br />

An additional role of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> in a horticultural environment may be as a predator of pest species. They are occasionally<br />

present in soybean fields in Florida where they prey on pest insects (Whitcomb et al. 1972). They prey on late instar<br />

larvae of a citrus pest in the Caribbean (Jaffe et al. 1990) and other citrus pests in California (deBach et al. 1951). They<br />

are abundant in disturbed rice fields in the Philippines (Way et al. 1998). They were often sampled at baits not foraged on<br />

by the dominant ants (S. geminata and P. fervens) (Way et al. 1998). They were abundant in some coconut palms in Sri<br />

Lanka, where they removed some eggs of a coconut pest, but were less effective than M. floricola (Way et al 1989). They<br />

may also be a significant predator of fly larvae and fleas (Pimentel 1955; Smith 1965). It is unclear if they have a role in<br />

population regulation of some pest and beneficial insects as Way et al. (1998) discussed in relation to S. geminata.<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> workers also gather small seeds from seedbeds of crops like lettuce and tobacco (Smith 1965).<br />

They do not appear to damage polythene irrigation tubing (Chang & Ota 1976).<br />

A7.3 Human impacts<br />

The crazy ant is primarily a pest in urban areas where it can become abundant indoors (wwwnew49; Lee 2002). It has<br />

been found on the top floors of large apartment buildings in <strong>New</strong> York, in hotels and flats in Boston and in hotel kitchens in<br />

San Francisco, California (wwwnew47). Its presence indoors, as well as its erratic behaviour and dark colour, make it very<br />

conspicuous. Workers are omnivorous in an urban setting, feeding on live and dead insects, seeds in seedbeds, fruits,<br />

plant and insect exudates, and many household foods. Consequently, they have potential negative and beneficial effects,<br />

but these have not been quantified independently of other pest ant species.<br />

Modular housing units in North Lauderdale (Florida) were inundated by the ant to the point that students were described<br />

as being ‘constantly in a state of turmoil’ (wwwnew47). Students’ lunches had to be kept in closed plastic bags placed on<br />

tables with each table leg sitting in a pan of water as a barrier. Elsewhere, a soda fountain business discontinued operation<br />

because of foraging by this ant (Smith 1965). No reports were found of crazy ants damaging wiring or any other<br />

structures within buildings.<br />

In a study carried out by pest controllers in Florida, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was primarily seen as a nuisance both inside and outside<br />

of domestic dwellings. They were generally not considered to infest food or wood items (Klotz et al. 1995).<br />

In monsoonal Australia, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is associated with human settlements, where it is one of the most common of the<br />

tramp species (Andersen 2000). In Penang, Malaysia, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was one of the more common ants sampled in<br />

buildings and was the first species to arrive in newly disturbed habitats or new buildings (Lee 2002). In Florida, it was<br />

most abundant in southern areas where it was described as a minor nuisance at outdoor-eating areas; it frequently<br />

entered buildings (Deyrup et al. 2000). In temperate North America (West Lafayette, Latitude 40.43) P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was<br />

only a minor component of the urban-building ant fauna, with Tetramorium caespitum, Prenolepis imparis, and Tapinoma<br />

sessile being numerically dominant (Scharf et al. 2004).<br />

This ant may transmit diseases. It was the second most common species in three Brazilian hospitals, and at least 20% of<br />

foragers carried pathogenic bacteria (Fowler et al. 1993).<br />

6

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

A8. Global distribution<br />

A8.1 Native range<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> probably originated in Africa (Wilson & Taylor 1967; Holway et al. 2002a) or Asia (Smith 1965,<br />

Wilson & Taylor 1967), but it is so widespread that it is difficult to determine its origin from ecological and historical<br />

records.<br />

A8.2 Introduced range<br />

It is one of the most common tramp ants in the tropics and subtropics, and is probably one of the most widely distributed<br />

of all the tramp ants (Fig. 2). It has also established in temperate regions where it is found in greenhouses and heated<br />

buildings. Some of the notable gaps in its distribution (e.g., southern China; Indonesia) may reflect the lack of published<br />

ant checklists from these regions rather than the absence of the species.<br />

A8.3 History of spread<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> is a common tramp species that is frequently intercepted and has been spread with trade for well<br />

over a century. It has been present in many countries outside its native range for a long time (over 100 years). In some<br />

locations it may reinvade frequently rather than establishing permanently; Trager (1984) suggests this is the case in<br />

California.<br />

A.9 Habitat range<br />

The crazy ant is highly adaptable, and can live in very dry as well as moist habitats. It is usually associated with disturbance,<br />

including disturbed natural environments like beaches (Jaffe 1993), the Dry Tortugas (Wetterer and O’Hara 2002),<br />

geothermal areas (Wetterer 1998), urban environments (Lee 2002; Andersen 2000; wwwnew47), farms (Collingwood et<br />

al. 1997), and even ships (Weber 1940). However, it is also present in some native vegetation in the tropics, e.g., conservation<br />

areas on offshore islands of Samoa (K. Abbott, pers. obser.). In cold climates, crazy ants nest in centrally heated<br />

apartments and other similar buildings such as glasshouses and airport terminals (e.g., Freitag et al. 2000; Naumann<br />

1994).<br />

7

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Fig. 2: Global distribution of <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong>. It is unclear whether Africa or Asia represents the original native range. Data are from the Landcare Research Invasive Ant Database<br />

(January 2005). The blue urban records are those where the ant was reported to be restricted to buildings.<br />

8

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(B) LIKELIHOOD OF ENTRY<br />

B1. Identification of potential pathways<br />

Crazy ants have been reported to be transported extensively by humans (Passera 1994) and associated with nearly all<br />

pathways taken by humans. They are commonly reported associated with potted plants (e.g., Clark 1941; Miller 1994).<br />

There are several potential pathways by which P. <strong>longicornis</strong> could enter <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>. Between 1997 and the end of<br />

2002, it was intercepted at the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> border 16 times; since then, a directive to identify all ants intercepted at <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Zealand</strong> ports has resulted in 47 further interceptions at the border (MAF records).<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> has been observed entering <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> on goods from a wide range of countries and commodities<br />

(Table 1 & 2). Most (> 80%) interceptions have been from sea freight and about 60% have been at Auckland sea<br />

or air ports with the remaining interceptions scattered widely around <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>. In recent years, post-border interceptions<br />

have occurred regularly at the Port of Auckland and elsewhere. In April 2002, samples taken from wharves at the<br />

Port of Auckland confirmed an incursion (Anon. 2004). Ants were subsequently found at a transitional facility in Mangere,<br />

South Auckland. In March 2003, three nests were found near the Mount Maunganui wharf of Port Tauranga. In 2004 a<br />

single worker was found at Sulphur Point (Port Tauranga) and a nest was observed and treated in Wellington. All these<br />

areas are being treated and/or monitored to ensure eradication.<br />

Most interceptions are of workers, but clearly queens are also being transported alive as colonies have been found postborder.<br />

Stopping this species arriving will be very difficult given its extensive distribution, close association with humans<br />

and ease of movement. Sea containers (full and empty) and timber appear to represent the main commodity pathways,<br />

but the high frequency with which this ant is found on ships means any vessel in any <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> ports is a potential risk.<br />

A pest risk analysis has been conducted specifically for the timber pathway after several interceptions on Jellico wharf in<br />

Auckland; these were associated with timber from the Pacific (Ormsby 2003).<br />

In Australia, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> has been intercepted frequently from many commodities and origins (Tables 3 & 4). Further<br />

analysis of the container data indicates the diverse range of goods with which they are associated with (Table 5).<br />

Fifteen interceptions from Hawaii in plants and fresh produce (data from January 1995 to May 2004; Source: Hawaii<br />

Department of Agriculture) list California and Georgia (USA) as origins not recorded in the Australia and <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong><br />

data.<br />

Some crazy ant interceptions at the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, Hawaiian and Australian borders are reported to have originated from<br />

countries not listed in the Landcare Research Invasive Ant Database as part of this ant’s distribution. These include<br />

Brunei, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Germany, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Malawi, Nauru, <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> (five interceptions in<br />

Australia), and Norfolk Island. If some of these origins are correct (and not errors or ants picked up in transit), this would<br />

further increase the risk pathways to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>. Crazy ants are often intercepted on ships and clearly there is scope for<br />

contamination of freight in transit.<br />

B2. Association with the pathway<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> is well established across the Pacific region and throughout much of the world’s tropical areas.<br />

Much trade arrives in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> from areas of the Pacific region where this ant is present. It is commonly associated<br />

with urban areas and buildings. Interceptions showing its association with a wide range of commodities suggest it is<br />

usually a stowaway; this makes it difficult to target high risk commodities for particular scrutiny. In addition, the wide<br />

range of countries in which it is established and from whence it has been intercepted makes targeting specific pathways<br />

for this ant species particularly difficult.<br />

9

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

B3. Summary of pathways<br />

A summary of freight coming to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> from localities within 100 km of known sites of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> infestation is<br />

presented in Fig. 3 (also see Appendix 1). During 2001-2003, total volumes of freight from localities near this ant were<br />

high, representing about 32.2% of total air freight and 34.9% of sea freight (44.2% of sea freight where the country of<br />

origin was reported). At many of the more temperate locations the densities of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> will likely be low and the<br />

distribution restricted; this reduces the risk of spread to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>.<br />

Table 1: Commodities from which P. <strong>longicornis</strong> has been intercepted at the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> border.<br />

Freight type 1997-2002 2003-Mar 2004<br />

Fresh produce 7 7<br />

Miscellaneous 1 3<br />

Personal effects 2<br />

Timber 1 9 b<br />

Containers 1 23 c<br />

Cut flowers 3<br />

On ship 2<br />

Incursion a 1 5<br />

a found near border but outside freight and association not known.<br />

b 4 interceptions from consignments on the same day on wharf in Auckland.<br />

c 3 empty.<br />

Table 2: Country of origin for <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> border interceptions of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>.<br />

Country 1997-2002 2003-Mar 2004<br />

Australia 2 1<br />

Fiji 5 9<br />

Indonesia 2<br />

Malaysia 1<br />

PNG 1 12<br />

Singapore 1 4<br />

Solomon Islands 5<br />

Thailand 1 2<br />

Tonga 4 3<br />

Vanuatu 1<br />

Vietnam 1<br />

Wallis & Futuna Islands 3<br />

10

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Table 3: Country of origin for Australian border interceptions of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Data from January 1986 to 30 June 2003<br />

(Source: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Canberra).<br />

Country No.<br />

Australia 4<br />

Brunei 1<br />

China 3<br />

Christmas Is. 8<br />

Cocos (Keeling) Islands 1<br />

East Timor 10<br />

Fiji 15<br />

France 2<br />

Germany, Fed. Repub. 1<br />

Guam 2<br />

India 2<br />

Indonesia 32<br />

Iran 1<br />

Ireland 1<br />

Italy 5<br />

Japan 2<br />

Malawi 1<br />

Malaysia 16<br />

Mauritius 1<br />

Nauru 1<br />

<strong>New</strong> Caledonia 1<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> 5<br />

Norfolk Is. 1<br />

Pacific Region 9<br />

Papua <strong>New</strong> Guinea 82<br />

Philippines 2<br />

Country No.<br />

Samoa (American) 2<br />

Ship 18<br />

Singapore 38<br />

Solomon Islands 4<br />

Spain 1<br />

Sri Lanka 1<br />

Syria 1<br />

Thailand 9<br />

Tonga 3<br />

United Arab Emirates 1<br />

Unknown 9<br />

USA 1<br />

Vanuatu 2<br />

Vietnam 4<br />

11

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Table 4: Freight types associated with Australian border interceptions of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Data from January 1986 to 30<br />

June 2003 (Source: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Canberra).<br />

Freight type No.<br />

Air baggage 27<br />

Container (full) 90<br />

Container (empty) 73<br />

Cut flowers 17<br />

Fresh produce 18<br />

Incursion 2<br />

Machinery/vehicles 10<br />

Miscellaneous 10<br />

Plants 3<br />

Post 3<br />

Ship 16<br />

Timber 15<br />

Wood products 20<br />

Table 5: Details of commodities listed from full containers intercepted at the Australian border containing P. <strong>longicornis</strong>.<br />

Data from January 1986 to 30 June 2003 (Source: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Canberra).<br />

Commodity No<br />

Packing 26<br />

External on shipping container 23<br />

Shipping container—unknown 16<br />

Stock food/dried foods 9<br />

Machinery/vehicle 5<br />

Metal 3<br />

Wooden furniture 2<br />

Stone carvings 1<br />

Glass 1<br />

Cookers 1<br />

Rubber 1<br />

Slate 1<br />

Gas cylinders 1<br />

12

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Fig. 3a: Summary of sea freight coming to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> from localities within 100 km of known sites of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Values represent the total freight (tonnes) during 2001, 2002 and<br />

2003 (source: Statistics <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>). Details of locations are given in Appendix 1.<br />

13

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Fig. 3b: Summary of air freight coming to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> from localities within 100 km of known sites of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Values represent the total freight (tonnes) during 2001, 2002 and<br />

2003 (source: Statistics <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>). Details of locations are given in Appendix 1.<br />

14

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(C) LIKELIHOOD OF ESTABLISHMENT<br />

C1. Climatic suitability of regions within <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> for the establishment of the<br />

ant species<br />

The aim of this section is to compare the similarity of the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> climate to the locations where the ant is native or<br />

introduced using the risk assessment tool BIOSECURE (see Appendix 2 for more detail). The predictions are compared<br />

with those for two species already established in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> (Ph. megacephala and L. humile) (Appendix 3). In addition,<br />

a summary climate risk map for <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> is presented; this combines climate layers that most closely approximate<br />

those generated by the risk assessment tool Climex.<br />

C1.1 Climate limitations to ants<br />

Given the depauperate ant fauna of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> (only 11 native species), and the success of many invasive ants throughout<br />

the world in locations with diverse ant faunas (e.g., Human & Gordon 1996), competition with <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> native ant<br />

species is unlikely to be a major factor restricting the establishment of invasive ants in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, although competition<br />

may be important in native forest where native ant abundance and diversity is higher (R. Harris, pers. obs.). For some<br />

species, the presence of other non-native ants in human modified environments may limit their distribution (e.g.,<br />

Solenopsis invicta has severely restricted the distribution of S. richteri and L. humile within the USA (Hung & Vinson 1978;<br />

Porter et al. 1988)) or reduce their chances of establishment. However, in most cases the main factors influencing<br />

establishment in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, should queens or colonies arrive here, are likely to be climatic.<br />

A significant relationship between maximum (and mean) daily temperature and foraging activity for both dominant and<br />

subordinate ants species indicated temperature rather than interspecific competition primarily determined the temporal<br />

activity of ant communities in open Mediterranean habitats (Cerda et al. 1998). Subordinates were active over a wider<br />

range of temperatures (Cerda et al. 1998). In California L. humile foraging activity was restricted by temperature attaining<br />

maximum abundance at bait at 34 o C, and bait was abandoned at 41.6 o C (Holway et al. 2002b).<br />

Temperature generally controls ant colony metabolism and activity, and extremes of temperature can kill adults or whole<br />

colonies (Korzukhin et al. 2001). Oviposition rates may be slow and may not occur at cooler temperatures (e.g., L. humile<br />

does not lay eggs below a daily mean air temperature of 18.3 o C (<strong>New</strong>ell & Barber (1913) quoted in Vega & Rust 2001)).<br />

At the local scale, queens may select warmer sites to nest (Chen et al. 2002).<br />

Environments with high rainfall reduce foraging time and may reduce the probability of establishment (Cole et al. 1992;<br />

Vega & Rust 2001). High rainfall also contributes to low soil temperatures. In high rainfall areas, it may not necessarily be<br />

rainfall per se that limits distribution but the permeability of the soil and the availability of relatively dry areas for nests<br />

(Chen et al. 2002). Conversely, in arid climates, a lack of water probably restricts ant distribution, for example L. humile<br />

(Ward 1987; Van Schagen et al. 1993; Kennedy 1998), although the species survives in some arid locations due to<br />

anthropogenic influences or the presence of standing water (e.g., United Arab Emirates (Collingwood et al. 1997) and<br />

Arizona (Suarez et al. 2001)).<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> has a cool temperate climate and most non-native ant species established here have restricted northern<br />

distributions, with most of the lower South Island containing only native species (see distribution maps in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong><br />

information sheets (wwwnew83)). Few adventive species currently established in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> have been collected<br />

outside urban areas in the cooler lower North Island and upper South Island (R. Harris, unpubl. data); for some this could<br />

reflect a lack of sampling, but the pattern generally reflects climatic limitations. In urban areas, temperatures are elevated<br />

compared with non-urban sites due to the warming effects of buildings and large areas of concrete, the “Urban Heat<br />

Island” effect (Changnon 1999). In addition, thermo-regulated habitats within urban areas (e.g., buildings) allow ants to<br />

avoid outdoor temperature extremes by foraging indoors when temperatures are too hot or cold (Gordon et al. 2001).<br />

15

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

C1.2 Specific information on P. <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

No specific information on temperature tolerances was found for P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Lee (2002) reported this ant to be most<br />

active in urban Malaysia at night (average air temperature of 25 o C with activity gradually ceasing late in the afternoon<br />

when temperatures peaked (averaging around 33 o C).<br />

The risk to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> might usefully be assessed from the crazy ant’s distribution in Hawaii, where it is restricted to the<br />

dry lowlands (< 900 m) (Reimer 1994). This suggests that <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> is too cold. Ant species that occur in Hawaii’s<br />

colder mountainous areas (900–1800 m, Reimer 1994) include Pheidole megacephala (which has a very restricted<br />

northern distribution in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> (Appendix 3)) and Linepithema humile. Linepithema humile also extends into the<br />

dry subalpine communities in Hawaii (1800–2700 m (Reimer 1994)), and its <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> distribution extends into the<br />

South Island (Appendix 3).<br />

C1.3 BIOSECURE analysis<br />

152 locality records were used for the assessment of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>, mostly from the introduced range (Fig. 4).<br />

The native plus introduced ranges show some overlap with all of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> for mean annual temperature (MAT) and<br />

mean temperature of the coldest month (MINT), because of records from heated buildings in very cold climates, e.g.,<br />

Quebec (Francoeur 1977) (Fig. 5; Table 6 & 7). Precipitation (PREC) is within the native and introduced ranges except in<br />

some south-western and alpine areas (Fig. 5a).<br />

The native and introduced (non-urban range) shows no overlap for MAT (Fig 5b). Minimum temperatures are unlikely to<br />

restrict establishment over most of lowland <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>. Precipitation is within the native and introduced ranges except in<br />

some south-western and alpine areas, but these regions are probably too cold for establishment outside permanently<br />

heated buildings. None of the other climate parameters are highly discriminating for lowland <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>.<br />

Climate summary<br />

The general climate summary for the international range of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> indicates low similarity to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, particularly<br />

compared to L. humile (Fig. 6). Climate summary graphs are less useful than individual climate layers as contrasts in<br />

the risk between species and regions of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> are less evident.<br />

Climate match conclusions<br />

Available data indicate that <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> has low climatic similarity with non-urban sites where P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is established.<br />

There is no overlap for MAT, and MINT is either at the lower end of international data or does not overlap. The lack<br />

of sufficiently high temperatures over the summer period for foraging and colony development is likely to severely limit the<br />

likelihood of this species’ establishing permanent populations in non-urban habitats in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>.<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> could survive in most urban areas in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, as it will inhabit heated buildings when<br />

outside temperatures are too cold. In summer it is likely to forage outdoors, and in warm microhabitats within urban areas<br />

colonies may persist outdoors throughout the year.<br />

16

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Fig. 4: Native (green), introduced non-urban (red), and introduced urban (orange) distribution records used in BIOSECURE analysis of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>.<br />

17

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Table 6: Comparison of climate parameters for native and introduced range and native and introduced non-urban range of<br />

P. <strong>longicornis</strong>.<br />

Mean Annual Temperature (°C)<br />

n Mean Minimum Maximum<br />

Native Range 7.0 24.5 23.2 26.2<br />

Introduced Range 145.0 23.2 4.3 29.3<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 24.3 17.5 29.3<br />

Minimum Temperature (°C)<br />

Native Range 7.0 19.7 17.7 23.1<br />

Introduced Range 145.0 15.3 -17.0 26.3<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 17.1 3.0 26.3<br />

Mean Annual Precipitation (mm)<br />

Native Range 7.0 1851.0 1125.0 3156.0<br />

Introduced Range 145.0 1456.0 9.0 3793.0<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 1497.0 9.0 3793.0<br />

Mean Annual Solar Radiation<br />

Native Range 7.0 14.3 11.5 17.5<br />

Introduced Range 145.0 16.1 9.2 22.9<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 16.3 12.1 22.9<br />

Vapour Pressure (millibars)<br />

Native Range 7.0 23.1 18.0 27.0<br />

Introduced Range 145.0 21.9 5.0 31.0<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 23.1 5.0 31.0<br />

Seasonality of Temperature (°C)<br />

Native Range 7.0 10.7 6.0 14.4<br />

Introduced Range 145.0 9.4 0.6 31.5<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 8.2 0.6 23.8<br />

Seasonality of Precipitation (mm)<br />

Native Range 7.0 369.7 199.0 854.0<br />

Introduced Range 145.0 151.0 3.0 632.0<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 157.8 3.0 632.0<br />

Seasonality of Vapour Pressure (millibars)<br />

Native Range 7.0 8.7 4.0 16.0<br />

Introduced Range 145 8.2 1.0 20.0<br />

Introduced Non-urban Range 130.0 7.8 1.0 19.0<br />

18

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Table 7: Range of climate parameters from (Table A2.1) <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> (N = 196 GRIDS at 0.5 degree resolution). Data<br />

exclude distant island groups (Chatham, Bounty, Antipodes, Campbell, Auckland, and Kermadec Islands).<br />

Parameter Min Max Mean<br />

MAT -0.5 16.6 10.9<br />

MINT -8.3 7.8 3.0<br />

PREC 356.0 5182.0 1765.0<br />

MAS 11.2 14.3 13.0<br />

VP 4.0 15.0 9.7<br />

MATS 6.4 10.6 8.8<br />

PRECS 23.0 175.0 60.5<br />

VPS 4.0 8.0 5.9<br />

19

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

a)<br />

b)<br />

Fig. 5: Similarity of a) native and introduced ranges and b) native and introduced non-urban ranges of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> to <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong><br />

for MAT, MINT, and PREC.<br />

20

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Fig. 6: Comparison of climate similarity of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> and the international ranges of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>, L. humile and Ph. megacephala based on the mean of the<br />

similarity scores of five climate layers (MAT, MINT, PREC, VP, and PRECS). This presentation approximates that produced by the risk assessment tool, Climex. The<br />

presentations represent native + introduced ranges.<br />

21

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

C2. Potential to establish in protected environments<br />

As described above, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is highly adaptable. It is closely associated with disturbed environments and will readily<br />

establish nest sites in greenhouses, buildings and urban environments and could survive in such habitats in temperate<br />

locations.<br />

C3. Documented evidence of potential for adaptation of the pest<br />

Trager (1984) suggested that the tolerance of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> for nesting sites with relatively low humidity, including crannies<br />

in walls, board and trash piles, palm thatching and dry litter contributes to its success.<br />

C4. Reproductive strategy of the pest<br />

In the tropics, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> produces sexual brood at any time of the year. However, in Gainesville, Florida (approximately<br />

30 degrees latitude), alate production is apparently limited to the warm, rainy months of the year (Trager 1984). Nuptial<br />

flights are thought not to occur (Trager 1984). On warm humid evenings, large numbers of males gather outside nest<br />

entrances. Periodically, winged queens emerge and the wings are removed while still callow. Mating was not observed, but<br />

Trager (1984) suggested that it occurred in these groupings around the nest entrance. Trager (1994) did not observe<br />

males to fly.<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> is polygynous (Passera 1994) and probably polydomous. Colonies and individuals from the<br />

same location appear to tolerate each other, but they behave aggressively towards individuals from distant sites (Lim et al.<br />

2003). Queens do not appear to cause this; instead, colony odors obtained through their diet appear responsible for the<br />

lack of intra-specific aggression (Lim et al. 2003).<br />

C5. Number of individuals needed to found a population in a new location<br />

To our knowledge, no research has been conducted on this aspect of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> ecology. However, an inseminated<br />

queen may have the capacity to start a new colony in isolation, but the likely mode of dispersal of this species is whole<br />

colonies being transported within freight. Workers alone are incapable of founding a new nest.<br />

C6. Likely competition from existing species for ecological niche<br />

This ant appears to be frequently displaced by more dominant species at baits, but in many other situations can survive<br />

and flourish. Rarely, it can become the numerically dominant ant. In Biosphere 2, an artificial biome constructed in<br />

Arizona, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> became the dominant ant species within approximately 2 years of first detection (Wetterer et al.<br />

1999). It displaced a suite of local native species that were deliberately introduced before the self introduction of P.<br />

<strong>longicornis</strong>. In Canada in a tropical glasshouse P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was in low abundance compared to Wasmannia<br />

auropunctata (Naumann 1994).<br />

Foraging workers of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> have been shown to discover baits before other ant species, and recruit in high numbers<br />

rapidly; however, they are usually replaced within an hour by more aggressive species that recruit additional foragers<br />

(Banks & Williams 1989; Lester & Tavite 2004). Wojcik (1994) monitored ant populations with bait traps on transects for<br />

21 years in Gainesville, FL, and found that Solenopsis invicta gradually increased from 0 to 43.3%. The presence of P.<br />

<strong>longicornis</strong> was positively correlated with S. invicta populations, so it appears to be able to coexist with S. invicta in Florida<br />

as it does in Brazil (Banks & Williams 1989). It was negatively associated with the presence of Pheidole megacephala in<br />

and around buildings in Brazil (Delabie et al.1995). Successful reduction of Monomorium spp. (M. pharaonis, M. destructor,<br />

and M. floricola) from buildings in Malaysia resulted in an increase in P. <strong>longicornis</strong> (and Tapinoma melanocephalum)<br />

activity, indicating that the Monomorium spp. were dominant (Lee 2002). In Sri Lanka, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was not present on<br />

coconut palms that had Oecophylla, as this species behaved aggressively towards P. <strong>longicornis</strong> (Way et al. 1989), and on<br />

22

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Floreana Island in the Galapagos, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was absent from samples at a village site where the abundance of M.<br />

destructor had increased (Von-Aesch & Cherix 2003). Fowler et al. (1994) found P. <strong>longicornis</strong> and T. melanocephalum in<br />

49 of 80 banana plantations surveyed in Sao Paulo, Brazil, but none had both species and both were absent from nearby<br />

tea and cocoa crops and native vegetation. On Santa Cruz Island in the Galapagos, P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was only sampled along<br />

a transect where Wasmannia auropunctata was absent (Clark et al. 1982). Pimentel (1955) reported that P. <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

avoided areas where S. geminata and T. melanocephalum were present, but would attack and drag away single S.<br />

geminata workers that tried to steal its food.<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> is likely to show considerable overlap in nesting sites with Linepithema humile (Argentine ant).<br />

Where L. humile is established, establishment of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> may be inhibited and if the two did coexist, P. <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

would likely be in relatively low abundance. Similarly, Doleromyrma darwiniana, which is also becoming more widespread<br />

around urban areas of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, could potentially compete with P. <strong>longicornis</strong> and reduce its chances of establishment.<br />

Pheidole megacephala has a very restricted <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> distribution so is unlikely to exert competitive pressure on<br />

P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Where M. pharaonis is established in heated buildings (this does not appear to be widespread in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Zealand</strong>), it may limit P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Coexistence is likely with other non-native ant species currently established in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Zealand</strong>, and native ant species are typically not abundant in disturbed habitats and so are unlikely to inhibit the establishment<br />

of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>.<br />

C7. Presence of natural enemies<br />

No reports of natural enemies of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> were found, and establishment in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> is only likely to be hindered<br />

by other ant species. It is not attacked by phorid flies that attack Solenopsis in South America (Porter et al. 1995).<br />

C8. Cultural practices and control measures applied in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> that may affect<br />

the ant’s ability to establish<br />

Practices at the point of incursion (e.g., seaports and airports) are likely to affect the ability of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> to establish at<br />

those sites. Presently, there are no routine treatments of port areas that would decrease the chances of survival for P.<br />

<strong>longicornis</strong>, except for ongoing incursion responses.<br />

Current (2002–2005) surveillance specifically for ants in and around ports is sufficiently thorough to detect large incursions,<br />

particularly in summer in northern areas where foragers are highly mobile and are attracted to surveillance baits. In<br />

addition, treatment of other invasive ant species in and around ports is likely to reduce the chances of survival of new<br />

propagules.<br />

In more southerly sites establishment may be more closely associated with heated buildings and ant surveillance would<br />

only detect an incursion if there is foraging outdoors, which would likely occur to some degree in summer.<br />

The importation procedures recommended by Ormsby (2003) for imported timber from the Pacific would reduce establishment<br />

probabilities from that pathway, but it is likely to be only one of many potential pathways for P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Also,<br />

Ormsby (2003) only considered management of the timber and not the risks associated with populations in vessels<br />

carrying the timber. Interception histories in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> and Australia would suggest ships are relatively commonly<br />

infested with P. <strong>longicornis</strong> (see B1. Identification of potential pathways).<br />

23

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(D) LIKELIHOOD OF SPREAD AFTER ESTABLISHMENT<br />

D1. Dispersal mechanisms<br />

Two methods of dispersal have together aided the spread of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> at local, regional, national and international<br />

scales—budding and human-mediated dispersal. The latter is probably more significant. P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is a ‘tramp’ ant<br />

(Holldobler & Wilson 1990; Passera 1994), renowned for transportation via human commerce and trade and commonly<br />

associated with a wide range of freight (see Association with Pathway section above).<br />

Natural dispersal is primarily by budding. Neither queens nor males appear to fly (Trager 1984). It is a rapid coloniser,<br />

often being the first species to arrive in a newly disturbed area (Lee 2002).<br />

D2. Factors that facilitate dispersal<br />

Colonies are characterised by extreme agility—a readiness to move when only slightly disturbed and an ability to swiftly<br />

discover new sites and organise emigrations—and often occupy local sites that sometimes remain habitable for only a few<br />

weeks or days (Holldobler & Wilson 1990). Trager (1984) reports a large swarm of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> emigrating after being<br />

flooded out of its nest by a sprinkler. Their occurrence in disturbed habitats increases the likelihood of their being spread<br />

more widely by events such as flooding. A close association with human habitats facilitates dispersal as a consequence of<br />

the movement of plants, rubbish and other commodities.<br />

D3. Potential rate of spread in its habitat range(s)<br />

With an absence of winged dispersal, potential rates of spread in new habitats will be limited if human-mediated dispersal<br />

is eliminated. No information on rates of spread of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was found. Their biology (budding, highly mobile colonies)<br />

suggests rates of spread will be similar to Linepithema humile. Expansion of L. humile through budding typically<br />

occurs over a relatively small scale, with estimates ranging from near zero in areas of climatic extremes up to 800 m/yr in<br />

recently invaded, highly favourable habitats (Holway 1998; Way et al. 1997; Suarez et al. 2001). In <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, the rate<br />

of spread of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> could be more limited than that of L. humile because of the patchy availability of suitably warm<br />

habitats.<br />

D4. Presence of natural enemies<br />

Other ant species (particularly Linepithema humile and Doleromyrma darwiniana) are likely to be the primary factor<br />

limiting spread of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Both L. humile and D. darwiniana may be abundant at sites where they are established in<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, and few other ants appear able to coexist with them (Ward & Harris in prep.; R. Toft, pers. comm.).<br />

24

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(E) THE ENVIRONMENTAL, HUMAN HEALTH AND ECONOMIC CONSE-<br />

QUENCES OF INTRODUCTION<br />

E1. Direct effects<br />

E1.1 Potential for predation on, or competition with <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>’s indigenous fauna<br />

Available data suggest that P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is generally not an ecologically dominant species, but is highly opportunistic,<br />

with its success centring on its ability to find food rapidly before other ant species. It is omnivorous and will take whatever<br />

food is available. It does best in highly disturbed or artificial environments where other species are less suited; in such<br />

locations it can become the numerically dominant ant (MacArthur & Wilson 1967; Jaffe 1993; Wetterer et al.1999),<br />

displacing other ants and affecting other invertebrates (Wetterer et al. 1999). Highly disturbed native habitats in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Zealand</strong> would include coastal dunes, intertidal areas, geothermal areas, and perhaps coastal scrub. The potential for<br />

establishment in those habitats is considered low because of climatic limitations. If P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was to establish in<br />

native habitat it would probably do so in the far north of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> and on northern offshore islands, all of which have a<br />

milder, subtropical climate. If the total ant biomass at a site increased as a result of the establishment of P. <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(not a certainty considering the limited climate suitability) there would likely be detrimental impacts on the native fauna,<br />

particularly the invertebrate community, with many species declining and localised extinctions being possible, placing<br />

invertebrate species with severely restricted distributions at risk. No native ants would be at risk of extinction because they<br />

are widely distributed and are present in forests that would serve as refuges. Disturbed native habitats are also those<br />

where L. humile is most likely to establish (Harris et al. 2002b) and it is likely that L. humile would displace P. <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>’s climate.<br />

Any dispersal into northern native habitats will take many years because of the dispersal mechanisms of this ant. Localities<br />

with low visitation rates, especially by boat or vehicle, may never have colonies transported into the area and natural<br />

dispersal rates by budding would be limited by the availability of suitable habitat.<br />

Urban areas generally have low native biodiversity values so the consequences of establishment would be minimal.<br />

E1.2 Human health-related impacts<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> does not sting or bite (Thompson 1990), and no reports were found of them spraying formic acid<br />

onto humans (unlike A. gracilipes). However, they could potentially vector pathogens in hospitals (Fowler et al. 1993) and<br />

commercial food outlets.<br />

E1.3 Social impacts<br />

In tropical areas, the frenetic behaviour of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is often considered irritating, and may deter people from sitting in<br />

areas where they are abundant. In <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, its presence within heated buildings such as hospitals and hotels would<br />

cause similar reactions and probably prompt pest control. Areas where abundant populations occur outdoors would<br />

probably be limited but where present they could be a nuisance.<br />

E1.4 Agricultural/horticultural losses<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> may be associated with honeydew-producing insects in large numbers (Wetterer et al. 1999). It<br />

is likely to reach large densities and be a pest only in glasshouse environments.<br />

A limited economic impact assessment in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> estimates potential treatment expenditure by affected sectors to<br />

be relatively small (up to $18 274 (Anon. 2004)).<br />

25

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

E1.5 Effect(s) on existing production practices<br />

There are likely to be no direct impacts on production practices from the establishment of this ant. However, if establishment<br />

occurs, the nursery trade may be a primary vector for the crazy ant’s spread around the country. If measures to stop<br />

spread were implemented within an area of incursion, freight companies and nurseries would be affected. Also people<br />

moving rubbish etc.<br />

E1.6 Control measures<br />

This section is largely based on the review of baiting by Stanley 2004.<br />

Crazy ants are difficult to control, with commercially available baits showing limited effectiveness (Hedges 1996a; Hedges<br />

1996b; Mampe 1997; Summerlin et al. 1998; Lee 2002; wwwnew51). The ant often nests some distance from its<br />

foraging area; nests can be in cracks in concrete often making them difficult to locate and control.<br />

Bait matrix (attractant + carrier): Experiments using food attractants found 80% of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> preferred honey over<br />

peanut butter (Lee 2002). Lee and Kooi (2004) report that baiting is seldom effective, particularly with paste and granular<br />

formulations, against P. <strong>longicornis</strong> in Singapore and Malaysia; however, they recommend sugar-based, liquid or gel<br />

formulations for control of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> (Lee 2002). Tuna (in oil) baits used in Biosphere 2 (in which P. <strong>longicornis</strong> was<br />

the dominant ant) were consistently more attractive to P. <strong>longicornis</strong> than the pecan cookie baits (carbohydrate) put out at<br />

the same time (Wetterer et al. 1999; J. Wetterer, pers. comm.). Few P. <strong>longicornis</strong> were attracted to oil baits in Hawaii<br />

(Cornelius et al. 1996), and in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>, foragers preferred sweet baits over protein baits during P. <strong>longicornis</strong> incursions<br />

(T. Ashcroft, pers. comm.).<br />

P. <strong>longicornis</strong> is attracted to sugar but does not have strong preferences for different sugars, unlike Pheidole megacephala<br />

(Cornelius et al. 1996). Sugar-based baits (1-cm cotton dental roll soaked in 20% sucrose-water) consistently attracted<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> spp. in a field trial in Arkansas (Zakharov & Thompson 1998). Peanut butter baits have been used in Hawaii<br />

to collect P. vaga and P. bourbonica (Gruner 2000). Sugar-based baits have controlled P. <strong>longicornis</strong> “pretty well” for<br />

homeowners in the San Antonio area, especially in the cooler winter months (wwwnew51).<br />

Toxicants and commercial baits: Hedges (1996b) reported P. <strong>longicornis</strong> would not feed for sufficient time on commercial<br />

baits to ensure effective control. Lee et al. (2003) found some evidence that Protect-B® (0.5% methoprene) baits and<br />

Combat Ant Killer® bait stations (1% hydramethylnon) are not effective against P. <strong>longicornis</strong>.<br />

Observations during incursions in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> showed that P. <strong>longicornis</strong> recruits well to Xstinguish (T. Ashcroft, pers.<br />

comm.). However, no formal testing of the attractiveness or the efficacy of this bait against P. <strong>longicornis</strong> has been<br />

undertaken. Exterm-An-Ant® (8% Boric acid + 5.6% sodium borate) has also been used against P. <strong>longicornis</strong> in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Zealand</strong> and although attractive to foragers (V. van Dyk, pers. comm.) its ability to kill queens within the nest is unknown.<br />

Trials to compare the attractiveness of Xstinguish, and Exterm-An-Ant® with other potential options for management of<br />

P. <strong>longicornis</strong> are being conducted in Queensland for MAF (M. Stanley, pers. comm.). <strong>Paratrechina</strong> spp. present in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Zealand</strong> (2 undescribed Australian species) do forage on Xstinguish (Harris et al. 2002a). Bait attractiveness trials on<br />

Palmyra Atoll showed P. bourbonica preferred sugar water, with Xstinguish next preferred (Krushelnycky & Lester 2003).<br />

P. bourbonica ignored Maxforce® granules (silkworm pupae matrix) and was not observed carrying away Amdro®<br />

granules (soybean oil on corn grit) (Krushelnycky & Lester 2003). Protein baits (fish meal; minced meat and eggs) are<br />

used in baits to control P. fulva in Colombia (Zenner-Polania 1990; Anon. 1996).<br />

Arkansas field trials on the non-target effects of Solenopsis invicta control using Logic® (fenoxycarb) and Amdro®<br />

(hydramethylnon) found that <strong>Paratrechina</strong> ants were one of the few genera not to decrease in Amdro®-treated plots, and<br />

their abundance more than doubled in the Logic®-treated plots (Zakharov & Thompson 1998). The authors concluded<br />

that <strong>Paratrechina</strong> is therefore not susceptible to Logic® or Amdro®. However, this study is difficult to interpret because<br />

observations of ants foraging on baits were not carried out and changes in abundance could have been a result of changes<br />

in the abundance of competitors.<br />

26

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

E2. Indirect effects<br />

E2.1 Effects on domestic and export markets<br />

No effects on domestic or export markets have been recorded. However, if P. <strong>longicornis</strong> became established in <strong>New</strong><br />

<strong>Zealand</strong> and transported to another country where they were absent, it could affect import health standards applied to<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> exports. However, with the very wide distribution of this ant most major international ports, particularly in<br />

tropical and subtropical zones, are likely to already have this ant established.<br />

E2.2 Environmental and other undesired effects of control measures<br />

There have been no documented cases of adverse non-target effects arising directly from the use of toxic baits to control P.<br />

<strong>longicornis</strong>. However, any bait used will likely be toxic to other invertebrates that eat it. Should Xstinguish baits be used<br />

for P. <strong>longicornis</strong>, extreme care will be needed near water as fipronil is highly toxic to fish and aquatic invertebrates<br />

(wwwnew81). There is no documented evidence of resistance of any ant to pesticides.<br />

27

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(F) LIKELIHOOD AND CONSEQUENCES ANALYSIS<br />

F1. Estimate of the likelihood<br />

F1.1 Entry<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> currently has a high risk of entry.<br />

This assessment is based on:<br />

• P. <strong>longicornis</strong> having been frequently intercepted at the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> border (16 times between 1997 and 2002,<br />

and 47 times between 2003 and March 2004 during a period of full reporting of interceptions).<br />

• this species having the potential to stowaway in a wide range of freight as it commonly nests in disturbed habitat<br />

and in close association with goods that are often transported.<br />

• dispersal being by budding. Colonies being polygyne and highly mobile if disturbed.<br />

• all these characteristics promote the chances of queens with workers being transported.The species being widespread<br />

globally relative to other tramp ant species.<br />

• its distribution includes much of the Pacific — a high risk pathway for ants entering <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>.<br />

Data deficiencies<br />

• not all ants intercepted at the <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> border are reported or identified and it is likely that current interception<br />

records underestimate entry of this species (as evident by the dramatic increase in interception reports in 2003). It is<br />

also not always clear from interception data if castes other than workers were intercepted.<br />

F1.2 Establishment<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> currently has a high risk of establishment.<br />

This assessment is based on:<br />

• there being suitable habitat for nesting close to sites of arrival or devanning (container unloading).<br />

• the ant having the capacity to establish nests in warm microclimates in urban areas in the northern part of the<br />

North Island and in close association with heated buildings elsewhere in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>.<br />

• the discovery of several persistent incursions of this species at Auckland and Mt Maunganui in 2003—2004,<br />

indicating the ability to establish beachhead populations.<br />

• the ant having a history of establishment within urban areas in countries with temperate climates, although in<br />

some cases, e.g., California, establishment is not thought to be permanent and there have been several<br />

reintroductions.<br />

• the low likelihood that the ant will encounter natural enemies, but a higher likelihood of competition from other<br />

adventive ants.<br />

• the presence of numerous pathways from <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>’s Pacific trading partners for budded colonies to arrive in<br />

<strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> in a fit reproductive state.<br />

• surveillance targeted at other invasive ants (particularly Solenopsis invicta) is likely to detect this species, because<br />

they will find baits rapidly but will probably be displaced by other species (such as L. humile, and S. invicta).<br />

28

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Data deficiencies<br />

• there is very little experimental data on climate tolerances of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. The climate assessment is based<br />

principally on consideration of climate from known sites of establishment of P. <strong>longicornis</strong>. Given the numerous<br />

interceptions, the frequency of recent incursions, and widespread distribution of this ant it is surprising that it is not<br />

already established. This may suggest that <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> conditions are not ideal. There is a lack of experimental data<br />

on survivorship and reproductive potential of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> at lower temperatures that mirror those of temperate<br />

climates.<br />

• there is need for a better data on the global distribution and associated localised environmental parameters of this<br />

ant. In particular follow-up on populations reported from temperate localities; are they still present, if so in habitats<br />

are they found, and what environmental conditions are they exposed to?<br />

• the ability of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> to establish at sites dominated by Linepithema humile is considered unlikely but is not<br />

experimentally proven.<br />

• there is no contingency plan for successful eradication of a large incursion of this species.<br />

F1.3 Spread<br />

<strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong> has a medium risk of spread from a site of establishment.<br />

This assessment is based on:<br />

• areas of <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> considered climatically suitable for the ant to colonise are available, although likely to be<br />

limited to urban areas.<br />

• suitable habitat occurs in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>. In temperate climates suitable habitat will primarily be urban, but some<br />

disturbed native habitat (costal dunes, intertidal areas, geothermal areas and perhaps coastal scrub), predominantly<br />

in the far north, could be colonised if climate predictions underestimate distribution.<br />

• the assumption that conditions enable colonies to grow large enough for budding to occur and that humanmediated<br />

dispersal would aid spread between urban centres.<br />

• colony development being relatively slow. Sub-optimal temperatures in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> will probably restrict foraging<br />

and colony development and extend the time taken for newly established colonies to reach sufficient size to produce<br />

reproductives and undergo budding.<br />

Data deficiencies<br />

• based on climate comparisons with the non-urban global distribution, northern <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong>’s climate is considered<br />

too cold for P. <strong>longicornis</strong> outside urban areas, but there is a lack of experimental data on developmental rates in<br />

relation to temperature to back up this assumption.<br />

• there is a lack of experimental data on the colony status (size and abiotic cues) that promotes budding in polygyne<br />

species.<br />

F1.4. Consequences<br />

The consequences of the presence of P. <strong>longicornis</strong> in <strong>New</strong> <strong>Zealand</strong> are considered low.<br />

This assessment is based on:<br />

• there being no medical consequences of establishment as the ant does not sting or spray formic acid.<br />

• the ant being only a minor nuisance pest both indoors and around domestic dwellings in limited locations, and<br />

29

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

probably an occasional pest in commercial premises through product contamination. Occasionally, in ideal conditions<br />

it may become a greater nuisance. Some pest control would probably be initiated where the ant was abundant but it is<br />

unclear if levels of control currently undertaken for other pests would increase significantly.<br />

• economic consequences being considered minor compared to those of L. humile, together with the probable<br />

overlap in suitable habitat for the two species in urban areas.<br />

• the low likelihood of environmental consequences even if the ant does establish in native habitats. In optimal<br />

climates this species is not ecologically dominant. Detrimental impacts have only been demonstrated in artificial<br />

(glasshouse) environments.<br />

Data deficiencies<br />

• there are no impact studies specifically focussing on this species in natural environments.<br />

• although predicted to establish, the extent of its likely distribution and its population densities in urban areas are<br />

unknown. There are no quantitative studies of its abundance and/or distribution in temperate cities, but also no<br />

reports of its being abundant or a significant pest in such environments.<br />

F2. Summary table<br />

Ant species: <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

Category Overall risk<br />

Likelihood of entry High Frequent interception. Medium - high<br />

Many potential pathways.<br />

Likelihood of establishment High Urban habitats suitable.<br />

Recent history of incursions.<br />

Likelihood of spread Medium Human assisted.<br />

Predominantly urban areas.<br />

Consequence Low Restricted distribution.<br />

Minor impacts.<br />

A detailed assessment of the Kermadec Islands is beyond the scope of this assessment.<br />

30

INVASIVE ANT RISK ASSESSMENT • <strong>Paratrechina</strong> <strong>longicornis</strong><br />

(G) References<br />

(NB: a copy of all web page references is held by Landcare Research (M. Stanley) should links change)<br />