Motuora Native Species Restoration Plan - Motuora Restoration ...

Motuora Native Species Restoration Plan - Motuora Restoration ...

Motuora Native Species Restoration Plan - Motuora Restoration ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

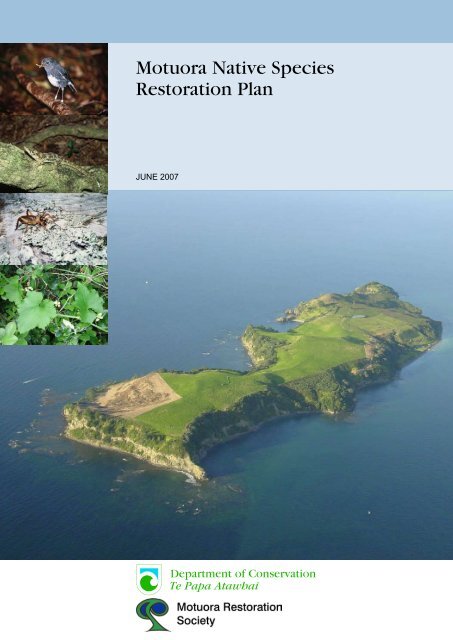

<strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Native</strong> <strong>Species</strong><br />

<strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

JUNE 2007

<strong>Motuora</strong><br />

<strong>Native</strong> <strong>Species</strong><br />

<strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong><br />

By Robin Gardner-Gee, Sharen Graham,<br />

Richard Griffiths, Melinda Habgood, Shelley<br />

Heiss Dunlop and Helen Lindsay

Foreward<br />

MOTUORA RESTORATION SOCIETY (INC)<br />

PO Box 100-132, NSMC, Auckland.<br />

Deciding to write a <strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> for <strong>Motuora</strong> was a huge undertaking for a voluntary<br />

group, especially since most of those whose help we needed already had busy lives.<br />

The project required surveys on the island to establish what plants and animals were already<br />

there, followed by much discussion and the writing of the various sections. These sections<br />

then had to be edited to make a unified whole.<br />

This document could not have been written without the enthusiasm, knowledge, and<br />

commitment of a group of keen environmentalists who put in long hours to produce the<br />

<strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>.<br />

The <strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Society thanks the many people and organizations who have<br />

provided information, advice and comment on this document.<br />

Particular thanks to:<br />

Robin Gardner-Gee for her invertebrate knowledge<br />

Sharen Graham for her bird knowledge<br />

Richard Griffiths for pulling the document together to present an overview of the whole<br />

island ecology<br />

Melinda Habgood for her reptile knowledge<br />

Shelley Heiss-Dunlop for her plant knowledge<br />

Helen Lindsay for her input into the plant section and for co-ordinating the project especially<br />

in the beginning<br />

Te Ngahere <strong>Native</strong> Forest Management for supporting this project<br />

Department of Conservation staff for support and encouragement.<br />

The <strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Society thanks you all for your generosity in sharing your learning<br />

and experience.<br />

Ray Lowe<br />

Chairman<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Society<br />

i

Executive Summary<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> is an 80 hectare island in the Hauraki Gulf to the south of Kawau Island. The island<br />

was farmed, but in 1990 the Mid-North Branch of the Royal Forest and Bird Protection<br />

Society initiated a plan to restore the island. <strong>Motuora</strong> is now jointly managed by the <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

<strong>Restoration</strong> Society (MRS) and DOC. The restoration goals are to re-establish a thriving<br />

indigenous ecosystem and to create a sanctuary for endangered fauna and flora.<br />

For the last fifteen years the restoration effort has been directed at re-afforesting the island’s<br />

pastures, a process due to be completed by 2010. It is now possible to plan for the<br />

introduction of fauna and flora that will contribute to the restoration goals. To establish a<br />

coherent introduction programme, MRS and DOC have commissioned this document: The<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Native</strong> <strong>Species</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>. This plan proposes a series of introductions to take<br />

place over the next decade (2007-2017) and it extends and updates the chapters of the<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Working <strong>Plan</strong> (Hawley & Buckton, 1997) that focus on the introduction<br />

of flora and fauna. The plan is intended to be a working document guiding restoration of the<br />

island’s biological communities and does not encompass other activities such as the<br />

management of cultural and historic resources.<br />

In contrast to some other restoration projects, on <strong>Motuora</strong> the initial focus is on establishing<br />

the foundations of a sustainable ecosystem which will then develop naturally. <strong>Species</strong><br />

proposed for introduction therefore include species typical of the area (e.g. locally common<br />

plants that are missing from <strong>Motuora</strong>), ecologically important species (e.g. seabird species that<br />

introduce marine nutrients into the island ecosystem), as well as threatened species (e.g. the<br />

Little Barrier Island giant weta). In order to preserve as much ecological integrity on <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

as possible, priority was given in the plan to species that are likely to have been on <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

prior to forest clearance and farming activity. Although there is little direct evidence of<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong>’s early flora and fauna, these species have been inferred from those present on other<br />

less modified local islands and the adjacent mainland. Particular attention has been given to<br />

flightless species (e.g. skinks) that are unlikely to re-colonise <strong>Motuora</strong> without human<br />

assistance. In addition, species under threat regionally or nationally have also been<br />

recommended for introduction if the emerging forest ecosystem on <strong>Motuora</strong> is able to<br />

provide suitable refuge for them. The plan identifies both the opportunities and the risks<br />

iii

inherent in translocating species – opportunities such as scope for public involvement,<br />

education and research, risks such as inadvertent introduction of weeds, parasites and diseases<br />

to the island.<br />

The plan systematically examines the four key groups that need to be considered in the island<br />

restoration: plants, invertebrates, reptiles and birds. For each group, the current situation on<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> is outlined and contrasted with the situation prior to disturbance. This is followed by<br />

a discussion of restoration options, with fully argued recommendations as to which species<br />

should be considered for introduction and when the introductions should take place. Habitat<br />

requirements, potential interactions with other species, and availability of source populations<br />

are outlined. <strong>Species</strong> considered unsuitable for introduction are also discussed. Finally the<br />

need for and nature of monitoring following the translocations is set out.<br />

For plants, the plan proposes that 76 locally common plants be introduced to <strong>Motuora</strong> to<br />

restore forest diversity. In addition, it is recommended that <strong>Motuora</strong> should provide refuge<br />

for 18 threatened and uncommon plants. These species are:<br />

Cook’s scurvy grass,<br />

Lepidium oleraceum<br />

Fireweed,<br />

Senecio scaberulus<br />

Green mistletoe,<br />

Tupeia antarctica<br />

Green mistletoe,<br />

Ileostylus micranthus<br />

Kakabeak,<br />

Clianthus puniceus<br />

Large-leaved milk tree,<br />

Streblus banksii<br />

Mawhai,<br />

Sicyos aff. australis<br />

<strong>Native</strong> geranium,<br />

Geranium solanderi “large petals”<br />

<strong>Native</strong> oxtongue,<br />

Picris burbidgeae<br />

NZ spinach,<br />

Tetragonia tetragonioides<br />

NZ watercress,<br />

Rorippa divaricata<br />

Sand tussock,<br />

Austrofestuca littoralis<br />

Small-flowered white bindweed,<br />

Calystegia marginata<br />

Shore spurge,<br />

Euphorbia glauca<br />

Parapara,<br />

Pisonia brunoniana<br />

Pimelia tomentosa<br />

Pingao,<br />

Desmoschoenus spiralis<br />

Wood rose,<br />

Dactylanthus taylorii<br />

iv

For invertebrates, the recommended species for translocation (3) are:<br />

Darkling beetle,<br />

Mimopeus opaculus<br />

Flax weevil,<br />

Anagotus fairburni<br />

Wetapunga,<br />

Deinacrida heteracantha<br />

For reptiles, the recommended species for translocation (8) are:<br />

Common gecko,<br />

Hoplodactylus maculatus<br />

Duvaucel’s gecko,<br />

Hoplodactylus duvaucelii<br />

Pacific gecko,<br />

Hoplodactylus pacificus<br />

Northern tuatara,<br />

Sphenodon punctatus punctatus<br />

Marbled skink,<br />

Cyclodina oliveri<br />

Robust skink,<br />

Cyclodina alani<br />

Whitaker’s skink,<br />

Cyclodina whitakeri<br />

Shore skink,<br />

Oligosoma smithii<br />

For birds, the recommended species for translocation (11) are:<br />

Seabirds<br />

Flesh footed shearwater,<br />

Puffinus carneipes<br />

Fluttering shearwater,<br />

Puffinus gavia<br />

Northern diving petrel,<br />

Pelecanoides urinatrix urinatrix<br />

Pycroft’s petrel,<br />

Pterodroma pycrofti<br />

White faced storm petrel,<br />

Pelagodroma marina<br />

Sooty shearwater,<br />

Puffinus griseus<br />

(after 2017)<br />

Forest birds<br />

Long tailed cuckoo,<br />

Eudynamys taitensis<br />

North Island robin,<br />

Petroica australis longipes<br />

Red crowned parakeet, Cyanoramphus<br />

novaezelandiae novaezelandiae<br />

Whitehead,<br />

Mohoua albicilla<br />

North Island saddleback,<br />

Philesturnus carunculatus rufusater<br />

(after 2017)<br />

Over time, these introductions have the potential to create a thriving native island ecosystem,<br />

with a diverse forest and numerous seabirds together sustaining an abundance of<br />

invertebrates, land birds and reptiles. The proposed introductions would also establish new<br />

populations of 14 threatened species and 14 species that are sparse or that have suffered<br />

decline on the mainland.<br />

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1<br />

OVERVIEW.................................................................................................................................................... 1<br />

OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS .......................................................................................................................... 3<br />

SECTION TWO: RESTORATION OF MOTUORA’S PLANT COMMUNITY .......7<br />

CURRENT SITUATION.................................................................................................................................... 7<br />

THE ORIGINAL FLORA OF MOTUORA ......................................................................................................... 10<br />

RESTORATION OPTIONS ............................................................................................................................. 10<br />

Non-threatened species................................................................................................................................. 10<br />

Threatened species....................................................................................................................................... 17<br />

MONITORING REQUIREMENTS.................................................................................................................... 21<br />

SECTION THREE: RESTORATION OF MOTUORA’S INVERTEBRATE<br />

FAUNA ......................................................................................................................... 23<br />

CURRENT SITUATION.................................................................................................................................. 23<br />

THE ORIGINAL INVERTEBRATE FAUNA OF MOTUORA................................................................................ 24<br />

RESTORATION OPTIONS ............................................................................................................................. 24<br />

Large flightless species.................................................................................................................................. 25<br />

Ecologically significant species........................................................................................................................ 29<br />

Threatened species....................................................................................................................................... 33<br />

Invertebrate Pests........................................................................................................................................ 37<br />

MONITORING REQUIREMENTS.................................................................................................................... 37<br />

SECTION FOUR: RESTORATION OF MOTUORA’S REPTILE FAUNA ........... 38<br />

CURRENT SITUATION.................................................................................................................................. 38<br />

THE ORIGINAL REPTILE FAUNA OF MOTUORA........................................................................................... 38<br />

RESTORATION OPTIONS ............................................................................................................................. 39<br />

Habitat and food requirements ...................................................................................................................... 40<br />

Duvaucel's gecko ........................................................................................................................................ 41<br />

Shore skink .............................................................................................................................................. 42<br />

Common and Pacific gecko ........................................................................................................................... 43<br />

Marbled, Robust and Whitaker’s skink......................................................................................................... 43<br />

Ornate skink ............................................................................................................................................ 44<br />

Tuatara ................................................................................................................................................... 45<br />

Reptile species considered unsuitable for translocation to <strong>Motuora</strong>.......................................................................... 45<br />

MONITORING REQUIREMENTS.................................................................................................................... 49<br />

SECTION FIVE: RESTORATION OF MOTUORA’S AVIFAUNA......................... 50<br />

CURRENT SITUATION.................................................................................................................................. 50<br />

<strong>Species</strong> introductions to date.......................................................................................................................... 51<br />

THE ORIGINAL AVIFAUNA OF MOTUORA ................................................................................................... 52<br />

RESTORATION OPTIONS ............................................................................................................................. 52<br />

Seabirds ................................................................................................................................................... 52<br />

Forest birds............................................................................................................................................... 57<br />

MONITORING REQUIREMENTS.................................................................................................................... 59<br />

SCHEDULE OF BIRD, REPTILE AND INVERTEBRATE SPECIES AND<br />

THREATENED PLANT SPECIES RECOMMENDED FOR INTRODUCTION<br />

TO MOTUORA BETWEEN 2007 AND 2017 ............................................................. 61<br />

REFERENCES............................................................................................................. 62<br />

vii

APPENDIX 1. RESEARCH PRIORITIES FOR THE MOTUORA RESTORATION<br />

PROGRAMME ............................................................................................................. 70<br />

APPENDIX 2: KEY STAKEHOLDERS AND USEFUL CONTACTS FOR THE<br />

TRANSLOCATION PROGRAMME .......................................................................... 72<br />

APPENDIX 3: VASCULAR FLORA OF MOTUORA ISLAND ................................ 73<br />

APPENDIX 4: MOTUORA PLANTING INVENTORY 1990-2006 .......................... 80<br />

APPENDIX 5. MAP OF EXISTING PLANTED AREAS ON MOTUORA ............. 81<br />

APPENDIX 6. VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE INNER HAURAKI GULF............. 82<br />

APPENDIX 7. LARGE BODIED BEETLES ON MOTUORA................................. 86<br />

APPENDIX 8. STICK INSECT SPECIES IN THE HAURAKI GULF .................... 87<br />

APPENDIX 9. CONSERVATION REQUIREMENTS OF AUCKLAND<br />

THREATENED INVERTEBRATES......................................................................... 88<br />

APPENDIX 10. INVERTEBRATES RECORDED ON MOTUORA ....................... 93<br />

APPENDIX 11. BIRDS RECORDED ON OR NEAR MOTUORA .........................101<br />

viii

Section One: Introduction<br />

Overview<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> lies in the Hauraki Gulf near Kawau Island, approximately 3km from the Mahurangi<br />

Heads and 5km from Wenderholm Regional Park. The 80 ha island is long, narrow and<br />

relatively flat-topped with coastal cliffs, sandy beaches and an extensive inter-tidal shelf.<br />

Although its highest point is only 75m above sea level, when viewed from the mainland<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> is a significant landscape feature. The island is composed mostly of a thick bed of 20<br />

million year old Parnell Grit with associated Waitemata Sandstones similar to that of other<br />

inner Hauraki Gulf islands such as Tiritiri Matangi and Kawau (Ballance, 1977; Edbrooke,<br />

2001).<br />

Much of the original coastal forest and shrub land vegetation was cleared long ago by Maori<br />

and European occupants, leaving remnant pohutukawa and karo/mahoe scrub growing on<br />

the coastal cliffs. In 1990 the Mid-North Branch of the Royal Forest and Bird Protection<br />

Society initiated a plan to restore the island and the island is now jointly managed by the<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Society (MRS) and DOC. The predator-free status of the island<br />

provides a unique opportunity to allow restoration of representative flora and fauna of both<br />

the Inner Hauraki Gulf Islands and Rodney Ecological Districts (McEwen, 1987).<br />

The goals of the restoration programme are to restore <strong>Motuora</strong> to a fully functioning, selfsustaining<br />

forest ecosystem that is (a) typical of the least modified islands in the region, (b)<br />

able to provide a safe refuge for compatible threatened species, and (c) able to be enjoyed by<br />

the many people who visit <strong>Motuora</strong> for relaxation and recreation. These goals recognize the<br />

role humans play in shaping <strong>Motuora</strong> and acknowledge that it is not possible to fully recreate<br />

the ecosystem that would have existed prior to human disturbance. To date restoration has<br />

concentrated on planting thousands of pioneer tree and shrub species to convert the retired<br />

open kikuyu grass pasture to native forest. It is anticipated that this initial planting<br />

programme will be complete by 2010, after which time the focus will change to the<br />

introduction and re-introduction of flora and fauna that contribute to the restoration goals.<br />

This plan proposes a series of introductions to take place over the next decade and extends<br />

and updates the chapters of the <strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Working <strong>Plan</strong> (Hawley & Buckton,<br />

1997) that focus on the introduction of flora and fauna. The plan is intended to be a working<br />

1

document guiding restoration of the island’s biological communities and does not encompass<br />

other activities such as the management of cultural and historic resources.<br />

A major focus of the plan is the establishment of a self-sustaining ecosystem and many of the<br />

species recommended for introduction are expected to contribute to the recovery of species<br />

already present on <strong>Motuora</strong> and the establishment of those species yet to be introduced. The<br />

introduction of seabirds, for example, is expected to benefit a number of the island’s<br />

invertebrate, reptile and plant species. Intensive ongoing species management is considered<br />

undesirable and the species recommended for introduction are expected to eventually form<br />

self-supporting populations. For this reason, the habitat requirements and presence of<br />

available habitat on <strong>Motuora</strong> were important factors in deciding when a species should be<br />

introduced. As a result of these considerations the plan focuses on terrestrial plants,<br />

invertebrates, reptiles and birds. Freshwater plants, fish, amphibians and bats were considered<br />

but discounted because no suitable habitat presently exists on <strong>Motuora</strong>. Habitat suitable for<br />

bats will not become available within the lifetime of this plan and <strong>Motuora</strong> is unlikely to ever<br />

provide sufficient habitat to support native freshwater fish and amphibian populations.<br />

Unlike many restoration projects that have focused on the introduction of threatened species<br />

with high public appeal, on <strong>Motuora</strong> the focus will be on ecosystem restoration. By reestablishing<br />

the foundations of a coastal forest community, natural succession will be able to<br />

run its course and the long term prospects for viability and sustainability of the island’s<br />

ecosystems will be more favourable. The first stage of this process has and continues to be<br />

the establishment of a range of habitat types and the necessary diversity to allow the assisted<br />

and self-establishment of ‘keystone’ species. Translocation has only been recommended for<br />

those species that are clearly unable to re-colonise by other means. For example, bellbird and<br />

kereru are important as pollinators and seed dispersers. However this plan does not propose<br />

to introduce these species as both are likely to arrive unassisted once suitable habitat is<br />

available on <strong>Motuora</strong>.<br />

<strong>Species</strong> that are likely to have been present on <strong>Motuora</strong> previously are considered the highest<br />

priority for introduction. Detailed reconstruction of <strong>Motuora</strong>’s original flora and fauna is not<br />

possible as paleological investigations have not been carried out on the island. Consequently,<br />

for the purposes of this plan, the historical presence of species on <strong>Motuora</strong> was inferred from<br />

comparisons with other less modified islands off the north east of the North Island,<br />

2

particularly those from within the Rodney and Inner Gulf Ecological Districts, and<br />

paleological information collected from the adjacent mainland. Close comparison with<br />

another unmodified island was impossible due to a lack of unmodified islands within the<br />

Inner Gulf Ecological District (Atkinson, 1986; McEwen, 1987).<br />

An ecological district reflects a local environment of interacting climatic, geological,<br />

topographical, biological features and processes all interrelated to produce a ‘characteristic<br />

landscape’ and range of biological communities (McEwen, 1987). The framework provides a<br />

sound approach for the restoration of natural plant and animal communities and a sensible<br />

platform for selecting suitable candidates for introduction. For restoration purposes native<br />

species can be sourced from other sites within the district or if this is not possible from an<br />

adjacent district (Simpson, 1992; WCC, 2001).<br />

<strong>Species</strong> that are unlikely to have been present but whose national or regional existence is<br />

threatened were considered for introduction to <strong>Motuora</strong> but were not recommended if their<br />

presence was considered likely to compromise the survival of other species or the long term<br />

ecological sustainability of the island. A detailed analysis of the suitability of species<br />

recommended for introduction to <strong>Motuora</strong> and the timing of their introduction is included.<br />

Both factors were considered critical to the success of the restoration programme and the<br />

ecological sustainability of the island. Other factors that were considered were the<br />

opportunities for education, advocacy and research.<br />

The plan also outlines the sequence of introductions, the likely source populations for the<br />

species and the timeframes translocations may take. Many species of plants and animals are<br />

referred to in the text by their common names. However, scientific names are provided in the<br />

tables that appear both in the document and in the appendices.<br />

Opportunities and Risks<br />

The species introductions outlined in this restoration plan are likely to create significant<br />

opportunities for both conservation and people. The absence of introduced mammalian<br />

browsers and predators on <strong>Motuora</strong> has created an ideal opportunity to restore a coastal<br />

forest ecosystem representative of the one present prior to human arrival. The island has and<br />

already is contributing to the recovery of regionally and nationally threatened species but its<br />

3

ability to do so will continue to increase over time. Establishing populations of threatened<br />

species on <strong>Motuora</strong> will not only provide greater security for those species but in time will<br />

also offer an additional source for establishing populations elsewhere.<br />

With the introduction of new species, particularly threatened species, the opportunities for<br />

advocacy are extensive. It is anticipated that the profile of <strong>Motuora</strong> will be raised and the<br />

restoration programme will receive more exposure. Securing funding and attracting<br />

sponsorship is likely to get easier and other opportunities for earning revenue may become<br />

available. Volunteer involvement in the restoration programme is likely to increase and the<br />

island’s appeal to volunteers already involved will be enhanced. Introductions of threatened<br />

species will generate greater public interest in the island as a destination and more visitors to<br />

the island are expected.<br />

Increased interest in the island offers significant opportunities for educating the public about<br />

conservation and restoration ecology. Introductions provide the ability to directly involve the<br />

public in the more exciting aspects of a restoration programme. Although translocations and<br />

the ongoing monitoring of establishing populations will require experienced people,<br />

opportunities for the involvement of volunteers and the public should not be overlooked.<br />

Interpretation and educational resources on the island have the ability to extend these<br />

learning opportunities.<br />

The translocation programme will generate numerous research opportunities and the<br />

opportunities for learning about ecosystem recovery and threatened species management are<br />

extensive. A list of some of the possible research topics that will be created is provided in<br />

Appendix 1. Relationships with research institutions should be developed and enhanced to<br />

fully capitalize on these opportunities.<br />

Alongside the opportunities created by the translocation programme come a number of risks<br />

that must be taken into account to ensure the success of each species introduction. <strong>Species</strong><br />

may fail to establish on <strong>Motuora</strong> for unforeseen reasons. To give species the best chance of<br />

establishing, translocation planning should be based on those techniques that have proven<br />

successful in the past. Best practice techniques for analogous species should be used for those<br />

species that have never been translocated before. It is essential that all translocations are fully<br />

documented not only to determine their success but also to develop and improve techniques<br />

4

for future transfers.<br />

Ecosystems are complex, and the introduction of some species may have unpredicted impacts<br />

on resident species or other introduced species. A common problem with translocations<br />

within New Zealand has been a lack of follow-up monitoring to ascertain the presence of<br />

competitive interactions. For the species introductions outlined in this plan, post-release<br />

monitoring is considered to be a key element that needs to be considered and resourced as<br />

part of translocation planning. The impact of a transfer on the source population also needs<br />

to taken into account.<br />

None of the species introductions are expected to require on-going intervention. However, it<br />

is possible that some species will require some short-lived management such as the provision<br />

of artificial refuges. The maintenance of suitable successional habitats is expected to occur<br />

through natural processes or as part of day to day island management (e.g. maintaining areas<br />

of open space for tracks and view points).<br />

As <strong>Motuora</strong>’s forest matures and canopy closure occurs, the ability of weed species to get a<br />

foot-hold on the island will diminish. However, the introduction of native and exotic plant<br />

species may increase in frequency as the island becomes more attractive to seed dispersers<br />

such as kereru and starlings (Heiss-Dunlop, 2004). Early detection and eradication of weeds is<br />

imperative to ensure negative impacts are minimized and an on-going weed control<br />

programme will be required.<br />

The introduction of new parasites and disease is a possibility that is ever present when<br />

moving a species from one place to another. A risk analysis will need to be completed on a<br />

case by case basis for each of the proposed species introductions and appropriate disease<br />

screening and quarantine provisions implemented. Veterinary advice will be required.<br />

Consultation with key stakeholders will be critical to ensuring the success of the translocation<br />

programme. Key stakeholders of <strong>Motuora</strong> and those concerned with source populations need<br />

to be involved at an early stage in translocation planning, to avoid wasting resources.<br />

Consulting widely and extensively will not only ensure that translocations are possible but<br />

may open up other opportunities in the future.<br />

5

While increased visitation to the island has a number of benefits it also carries many<br />

associated risks. The greatest threats that visitors bring to the island are fire and the<br />

introduction of pest animals and plants. There are many examples of seeds of weed species<br />

being carried in boots and jacket pockets and rodents and invertebrates arriving on islands off<br />

boats and in personal equipment. The consequences of inadvertent pest introduction can not<br />

be underestimated and some species have the potential to seriously compromise the<br />

restoration programme.<br />

Since the island is an open sanctuary, advocacy and education will be the two most important<br />

tools in minimising the risks of fire and pest invasion, and the island ranger has a crucial role<br />

to play in this regard. Highlighting the risks and informing visitors of the simple precautions<br />

that need to be taken prior to their arrival should be part of day-to-day island management.<br />

Educational and interpretive material on and off the island can be used to reinforce these<br />

messages. Setting a good example is everyone’s responsibility. The central tenet behind the<br />

management of these risks is the principle that prevention is better than cure.<br />

Tracks and visitor facilities will need to be upgraded over time to handle the growing number<br />

of visitors. Poaching of threatened plants and animals is considered unlikely but should be<br />

monitored.<br />

6

Section Two: <strong>Restoration</strong> of <strong>Motuora</strong>’s <strong>Plan</strong>t Community<br />

Current Situation<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong>’s long history of human occupation, cultivation and in particular pastoral farming<br />

removed most of the island’s original forest and left a vegetation cover dominated by exotics<br />

(Hawley & Buckton, 1997). In 1990 the focus for the island changed and a volunteer-led<br />

restoration programme began. <strong>Restoration</strong> efforts gained momentum in 1995 with the<br />

formation of the <strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Society. By 2040 it is expected that the 80 ha island<br />

will be fully replanted and support around 75 ha of regenerating coastal broadleaf forest (see<br />

Table 1). Five hectares of the island is to be left in grassland and managed as open space.<br />

The oldest forests on <strong>Motuora</strong> total approximately 20 ha and are scattered along the<br />

perimeter of the island. The east-facing Pohutukawa Bay forest remnant provides the best<br />

representation of naturally-regenerating coastal forest on the island. Typical coastal species<br />

dominate, including pohutukawa, karo, houpara, coastal karamu, kawakawa, coastal astelia,<br />

and rengarenga (see Appendix 3 for botanical names of plants on <strong>Motuora</strong>). By 2006<br />

approximately 35 of the 60 ha of retired pasture had been planted in early successional species<br />

and it is anticipated that a further 20 ha will be planted by 2010 (see Table 1). A planting<br />

inventory is provided in Appendix 4 in conjunction with a map outlining the areas planted<br />

(Appendix 5) with species numbers planted between 1999 and 2006.<br />

At the outset of planting in 1990, seed was sourced from the island where sufficient diversity<br />

remained. Local seed sources included mahoe, pohutukawa, karo, karamu, hangehange,<br />

houpara, whau, ngaio, broom, mahoe, akeake, taupata, and puriri. There were few manuka,<br />

akeake, and flax remaining on the island, with a single kowhai and karaka. Some seed was<br />

collected from these species; however additional seed came from Tiritiri Matangi. <strong>Species</strong><br />

either non-existent on <strong>Motuora</strong> or providing insufficient seed included kohekohe, kanuka,<br />

koromiko, kowhai, cabbage tree, wharangi, and five-finger. These species were also sourced<br />

from Tiritiri Matangi. Cuttings were taken from a single remaining totara tree as it did not<br />

produce seed and it is recommended that totara seed be sourced from other nearby<br />

populations. More recently taraire seed has been sourced from Mahurangi West (H. Lindsay,<br />

pers. comm.).<br />

7

By late 2006 over 205,000 plants had been planted since the revegetation programme began<br />

in 1990 (Appendix 4). During the period from 1990 to1998 nearly 44,000 pioneering plant<br />

species were planted, and from 1999 to late 2006 a further 162,000 plants were planted. More<br />

comprehensive planting records have been kept since 1999 (Appendix 4) detailing species and<br />

their numbers. Between 1999 and 2006 late successional species have been planted including<br />

kohekohe (531), karaka (1094), puriri (248), and taraire (80).<br />

A vascular flora survey completed on <strong>Motuora</strong> in 1987 found 14 ferns and more than 125<br />

higher plants but plants growing around the houses at Home Bay that were either deliberately<br />

planted or have escaped were not recorded (Dowding 1988). A further investigation of the<br />

island’s vascular flora completed in 2006 resulted in a significant increase in the number of<br />

species recorded on the island, adding a further 138 species (Appendix 3).<br />

A total of 288 taxa have been recorded on <strong>Motuora</strong> of which 123 (43%) species are native,<br />

and 165 (57%) are naturalised exotics including garden relicts and escapes (Appendix 3).<br />

During the 2006 survey, 22 taxa recorded by Dowding (1988) and Hawley and Buxton (1997)<br />

were not located. Of these, eleven were native species including a coprosma hybrid, Geranium<br />

solanderi “large petals”, hebe, native fireweed, nertera and true maidenhair. More time spent<br />

searching may yet reveal their location. The remaining five native species (dwarf cabbage tree,<br />

Glen Murray tussock, pigweed, tawapou and thin-leaved coprosma) are most likely to be<br />

extinct on <strong>Motuora</strong> and should be considered for future re-introduction.<br />

Ten introduced species noted in previous listings (Dowding, 1988, Hawley & Buckton, 1997)<br />

can also be considered extinct from <strong>Motuora</strong>. These include juniper, cotoneaster, California<br />

privet, false acacia, hemlock, ivy, lemon scented jasmine, purple nut sedge and tamarisk. Two<br />

new exotic species have recently self-introduced to the island. These species were the invasive<br />

holly fern and Chinese privet and both have been controlled (Lindsay, 2006).<br />

Based on the 2006 botanical survey it appears that few native higher plants have selfintroduced<br />

to the island. A well-established lancewood hybrid (Pseudopanax crassifolius x P.<br />

lessonii) was found above Still Bay. There are no known lancewoods present on the island,<br />

although there is a possibility a population exists in an inaccessible location unaccounted for.<br />

Sixteen new ferns were identified in the recent survey. However it is difficult to positively<br />

confirm their arrival status. There have been few natural introductions of woody plant species<br />

8

(native or exotic) since the outset of the project suggesting there is very little bird movement<br />

between <strong>Motuora</strong>, the mainland and surrounding islands. In order to attract more native seed<br />

dispersers such as kereru and tui it may be necessary to establish increased species diversity so<br />

that seasonal food resources become more attractive.<br />

Intensive weed control has been an integral component of the restoration programme on<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> since 1998, resulting in a significant reduction of weed numbers (Lindsay, 2006). An<br />

on-going weed control programme has ensured weed species are kept to a minimum and are<br />

not a threat to existing or future restoration plantings. Concerted efforts have largely reduced<br />

the boneseed infestation to the northern and north-western cliffs of the island, and boxthorn<br />

populations are now limited to a few isolated infestations (Lindsay, 2006). A mature stand of<br />

macrocarpa remains, reminiscent of European farming practices, but most of the pine has<br />

now been removed. Other exotic species such as madeira vine, climbing asparagus and<br />

pampas are also targeted and continued vigilance to prevent new introductions is necessary.<br />

Table 1: The Current And Predicted Area (In Hectares) Of Potential Vegetation Cover<br />

From 2005 To 2040 On <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

Vegetation type<br />

Present<br />

2005<br />

Predicted<br />

2010<br />

Predicted<br />

2020<br />

Predicted<br />

2030<br />

Predicted<br />

2040<br />

Naturally regenerating coastal forest<br />

(pohutukawa/broadleaf canopy)<br />

20 ha 20 ha 20 ha 20 ha 20 ha<br />

Grass (retired pasture) 25 ha 5 ha 5 ha 5 ha 5 ha<br />

New plantings<br />

(open canopy; rank grass/herbs/young<br />

natives;

The Original Flora of <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

There are few records of the past vegetation of <strong>Motuora</strong>. The Inner Gulf islands including<br />

Tiritiri Matangi (220 ha), Kawau Island (2058 ha), Moturekareka (19 ha), Motuihe Island (179<br />

ha), Noises Islands group (24.5 ha), and the adjacent forest remnants of Mahurangi (East and<br />

West) and Wenderholm offer suitable modern day analogues to <strong>Motuora</strong> due to their similar<br />

ecological characteristics and geological makeup (Atkinson, 1960a; Ballance, 1977; Ballance<br />

and Smith, 1982; Grant-Mackie, 1960). However, their current vegetation composition<br />

requires further interpretation to remove the sources of human induced influences (Wright,<br />

1988). An understanding of remnant vegetation composition in conjunction with<br />

palynological investigations (Elliot, 1995; Heiss-Dunlop, Deng, Craig & Nichol, in press) of<br />

ecologically similar islands is the key to identifying general species assemblages appropriate<br />

for restoration purposes.<br />

Based on historical information and literature, the island’s bioclimatic profile, and existing<br />

intact forest remnants within the same ecological district (and the adjacent mainland), it can<br />

be assumed that <strong>Motuora</strong> was most likely covered in a coastal broadleaf forest (with a minor<br />

component of mixed conifer forest species) similar to that of comparable Inner Gulf islands<br />

and the adjacent mainland with similar palaeoenvironmental histories.<br />

<strong>Restoration</strong> Options<br />

The past restoration efforts on <strong>Motuora</strong> have created suitable habitat to introduce plants that<br />

were known to have been present in the past (e.g. Coprosma areolata, Cordyline pumilio, Einadia<br />

triandra, Geranium solanderi “large petals”, Nertera and Pouteria costata), and the introduction of<br />

species we can assume would have grown there based on historical literature (Buchanan,<br />

1876,:Kirk, 1868; Kirk, 1878), pollen records from islands within the Inner Hauraki Gulf<br />

Ecological District (Elliot, 1995; Heiss-Dunlop et al., in press), from contemporary Inner<br />

Gulf island models (Cameron and Taylor, 1992; de Lange & Crowcroft, 1996; de Lange &<br />

Crowcroft, 1999; Esler, 1978; Esler, 1980; Tennyson, Cameron & Taylor, 1997) and examples<br />

of remnant coastal broadleaf forest on the adjacent mainland (Young, 2005; Young, in press).<br />

Non-threatened species<br />

Appendix 6 provides a typical range of plants occurring either currently or historically on a<br />

number of islands similar to <strong>Motuora</strong> (within the Inner Hauraki Gulf Islands Ecological<br />

District and the Rodney Ecological District). It highlights the current species on <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

10

(including planted species) and identifies species suitable for re-introduction and where there<br />

are known populations. This information forms the basis of species selection for reintroduction<br />

to <strong>Motuora</strong>, listed in Table 2. It is recommended that Mahurangi East,<br />

Mahurangi West, Wenderholm, Tiritiri Matangi, and Kawau Island be the main seed sourcing<br />

sites due to their ecological similarities with <strong>Motuora</strong> and accessibility. In particular,<br />

Mahurangi East (80 ha), Mahurangi West (100 ha), and Wenderholm (75 ha) provide a<br />

representative range of species that most likely existed on <strong>Motuora</strong>, due to the wide variety of<br />

habitat types they support. Suitable habitat is currently available on <strong>Motuora</strong> to introduce any<br />

of the species recommended in Table 2 and seed sources are readily available for common<br />

species. Limiting factors will be locating seeding trees of the less common species and<br />

propagation success. The Auckland Botanical Society may be able to assist in identifying<br />

suitable trees as seed sources from Mahurangi (East and West) and Wenderholm. Tiritiri<br />

Matangi may also be able to provide seed when required.<br />

Management of the ecological processes on <strong>Motuora</strong> is essential to ensure a fully functioning<br />

ecosystem develops. Without intervention it is likely the forest would become dominated by<br />

karo and pohutukawa. It is envisaged to recreate a coastal broadleaf forest, including a minor<br />

component of mixed conifers. The canopy of a typical coastal broadleaf forest comprises<br />

taraire, tawa, kohekohe, pohutukawa and puriri. Also present but in fewer numbers would be<br />

titoki, tawapou, rewarewa, kowhai, mangeao and milk tree species (Streblus banksii and Streblus<br />

heterophyllus). Emergent trees would include kahikatea and northern rata. Typical understorey<br />

species would include nikau, rangiora, hangehange, mahoe, lacebark, coprosma species (e.g.<br />

Coprosma arborea, C. areolata, C. grandifolia and C. rhamnoides), putaputaweta, and silver fern.<br />

Common lianes include rata vines (Metrosideros diffusa, M. fulgens and M. perforata) and<br />

supplejack, with the epiphyte Collospermum hastatum abundant in mature canopy trees. The<br />

ground cover would typically consist of fern species (e.g. Adiantum spp., Asplenium spp., and<br />

Polystichum neozelandicum subsp. neozelandicum), sedges (e.g. Carex flagellifera), cutty grass (Gahnia<br />

lacera), and hook grass (Uncinia uncinata).<br />

It is recommended a mix of conifers is established (e.g. kauri and podocarp species including<br />

kahikatea, miro, rimu, tanekaha and totara) to provide greater species diversity, increase<br />

seasonal food sources, and additional interest on the island. However, it is envisaged they will<br />

be planted in low numbers with the main purpose of establishing a seed source on the island.<br />

Kauri forests are not exclusive forests but are mixed-type forests in which kauri may occur as<br />

11

isolated specimens or in groves. Often kauri forests consist of kauri in association with trees<br />

such as taraire, tawaroa and northern rata with numerous other species of shrubs, epiphytes<br />

and ferns. Taraire found in association with kauri appear to take their place and may form the<br />

final climax community of the manuka-kauri-taraire sequence (Salmon, 1978). It is envisaged<br />

to plant a small kauri grove with tanekaha on a drier ridge line (e.g. areas I or F; see map in<br />

Appendix 5). Miro can be scattered throughout the forest in low numbers, and totara should<br />

be planted in drier areas. Taraire prefer moister situations and could be planted on the slopes<br />

in areas K and J for example.<br />

In addition to pioneer species and late successional woody plants, other species are required<br />

to restore wetland seepage areas. It is recommended to monitor existing habitats for selfintroductions<br />

and continue supplement plantings of sedges (e.g. Carex secta) around dams.<br />

Hook grass and the sedge (Carex flagellifera) were not found in the 2006 survey although they<br />

are a typical species of coastal forests. It is recommended they be planted in low numbers<br />

throughout existing forest remnants to establish permanent populations.<br />

Once the wet areas such as Coromandel Gully and the valley above Pohutukawa Bay have an<br />

established cover they will be suitable for future plantings of nikau (Rhopalostylis sapida),<br />

kahikatea, kiekie and pukatea in low numbers. Nikau could be planted immediately into<br />

existing moist areas alongside streams in Pohutukawa Bay, Coromandel Gully and<br />

Macrocarpa Bay. Since nikau take many years before they reach fruiting maturity it is<br />

recommended seed is sourced (e.g. from Mahurangi East) as early as possible.<br />

Open areas adjacent to tracks should be planted in Muehlenbeckia complexa and M. australis to<br />

improve reptile habitat, enhance reptile viewing opportunities, and to suppress weeds.<br />

Additional areas should be planted in low-growing non-woody species such as flax, shrubby<br />

haloragis and coastal toetoe, and areas of bracken should be left to naturally regenerate.<br />

<strong>Native</strong> ground covers should also be used in managed view spaces and recreational areas.<br />

The numbers of specific pioneer species planted should be increased to support future fauna<br />

introductions. These include coprosma species (Coprosma areolata, C. arborea, C. grandifolia and<br />

C. rhamnoides), five-finger, hangehange, kowhai, mahoe (both Melicytus novae-zelandiae and M.<br />

ramiflorus), mingimingi, and ngaio.<br />

12

Based on past planting numbers approximately 25,000-30,000 plants are planted each year<br />

covering an area of 5-6 ha (Appendix 4). Over the next ten years it is envisaged a greater<br />

percentage of the plants will comprise late successional species (in-fill planting in well-<br />

established revegetated areas) and a range of mid-canopy forest species will be introduced.<br />

The coastal species recommended for introduction (listed in Table 2) are to be planted in low<br />

numbers at a number of suitable coastal locations in order to establish self-sustaining<br />

populations.<br />

13

Table 2: <strong>Species</strong> Recommended For Introduction To <strong>Motuora</strong> (2007-2017) Including<br />

Suggested <strong>Plan</strong>ting Numbers.<br />

Key:<br />

Low numbers = 10-100<br />

Medium = 100-1000<br />

High = 1000-5000<br />

+ = insufficient numbers on <strong>Motuora</strong>, additional<br />

seed sources required<br />

C = Casnell Island (Maunganui)<br />

K = Kawau Island<br />

KH = Kohatutara Island<br />

ME = Mahurangi East Regional Park<br />

MR = Moturekareka Island<br />

MT = Motutara Island<br />

MW = Mahurangi West Regional Park<br />

NG = Noises Islands group<br />

TM = Tiritiri Matangi<br />

W = Wenderholm<br />

Forest and Coastal Shrub <strong>Species</strong><br />

Botanical name Common name Potential source<br />

populations<br />

Numbers to be planted<br />

Agathis australis kauri MW, W, K Low<br />

Alectryon excelsus titoki MW, ME, W Medium<br />

Alseuosmia macrophylla toropapa W, K Low<br />

Aristotelia serrata wineberry K Low<br />

Astelia solandri perching lily W, K Low<br />

Beilschmiedia tarairi taraire MW, ME, W, TM, K Medium<br />

Beilschmiedia tawaroa tawaroa ME, MW, W, K, TM Medium<br />

Carpodetus serratus putaputaweta W, K Low<br />

Ozothamnus leptophyllus tauhinu TM, K Low<br />

Clematis paniculata + clematis MW, MR, W, TM Low<br />

Coprosma arborea tree coprosma MW, W, TM, K Medium<br />

Coprosma areolata thin-leaved coprosma MW, ME, W, TM Medium<br />

Coprosma grandiflora large-leaved coprosma ME, W, TM, K Medium<br />

Coprosma lucida shining karamu TM, K Medium<br />

Coprosma propinqua mingimingi W, TM Low<br />

Coprosma spathulata W Low<br />

Cordyline pumilio dwarf cabbage tree MW, TM, K Low<br />

Corynocarpus laevigatus karaka MW, ME, W Medium<br />

Cyathodes juniperina prickly mingimingi TM, NG Low<br />

Dacrycarpus dacrydioides kahikatea MW, ME, W Low<br />

14

Dacrydium cupressinum rimu MW, W Low<br />

Dicksonia squarrosa wheki, rough tree fern MW, ME Low<br />

Dysoxylum spectabile kohekohe MW, ME, W, TM Medium<br />

Freycinetia banksii kiekie MW, ME, W Low<br />

Fuchsia excorticate tree fuchsia W, TM Medium<br />

Gahnia setifolia MW, W Low<br />

Griselinia lucida puka W Low<br />

Hedycarya arborea pigeonwood MW, ME, W, TM Medium<br />

Knightia excelsa rewarewa MW, ME, W, TM Medium<br />

Laurelia novae-zelandiae pukatea W Low<br />

Leucopogon fasciculatus + mingimingi MW, MR, W Medium<br />

Litsea calicaris mangeao ME, W, TM Low<br />

Melicytus novae-zelandiae + coastal mahoe MT, TM, NG Medium<br />

Melicytus ramiflorus mahoe MW, ME, W Medium<br />

Metrosideros diffusa white climbing rata Low<br />

Metrosideros fulgens orange rata vine K Low<br />

Metrosideros perforate small-leaved rata ME, MW, W, K Low<br />

Muehlenbeckia australis MW, T Low<br />

Nestegis apetala coastal maire Mokohinau Low<br />

Nestegis lanceolata white maire MW, W, K Low<br />

Olearia rani heketara W, K Low<br />

Parsonsia heterophylla NZ jasmine MW, ME, W, TM Low<br />

Passiflora tetrandra native passion vine W Low<br />

Peperomia urvilleana MW, ME, MR, MT Low<br />

Phyllocladus trichomanoides tanekaha MW, W Low<br />

Pittosporum cornifolium perching pittosporum W Low<br />

Pittosporum tenuifolium kohuhu K Low<br />

Pouteria costata tawapou W, ME, TM Medium<br />

Podocarpus totara + totara ME, MW Low<br />

Pomaderris kumeraho kumaraho T Low<br />

Prumnopitys ferruginea miro MW, W Low<br />

Prumnopitys taxifolia matai MW, W Low<br />

Pseudopanax arboreus + five-finger MW, W, TM, K Medium<br />

Pseudopanax crassifolius lancewood MW, W, K Low<br />

Rhabdothamnus solandri NZ gloxinia MW, W, TM, K Medium<br />

Rhopalostylis sapida nikau ME, MW, W, TM Medium<br />

Ripogonum scandens supplejack ME, MW, W, TM Low<br />

Rubus cissoids bush lawyer MW, W Low<br />

15

Schefflera digitata seven-finger, pate W, TM Low<br />

Solanum aviculare poroporo MW, TM Low<br />

Sophora chathamica coastal kowhai ME, W Medium<br />

Streblus banksii large-leaved milk tree MW, N (ME & W?) Low<br />

Streblus heterophyllus small-leaved milk tree MW, ME, W, TM Low<br />

Vitex lucens + puriri MW, ME, W, TM, K Medium<br />

Forest and Coastal Shrub <strong>Species</strong><br />

Botanical name Common name Potential source<br />

populations<br />

Location to be planted<br />

Einadia triandra pigweed MR Splash zone.<br />

Einadia trigonos subsp.<br />

Trigonos<br />

pigweed MR, KH Splash zone.<br />

Linum monogynum NZ linen flax, rauhuia NG, Motuhoropapa,<br />

Coastal cliffs, rocky areas and sand<br />

(Cameron, 1998;<br />

Mason, Knowlton &<br />

Atkinson, 1960)<br />

dunes.<br />

Selliera radicans selliera ME, TM (bay east of Coastal sands and rocky places,<br />

Fishermans Bay), stream margins.<br />

Tetragonia trigyna<br />

beach spinach, NZ TM, NG Coastal sands, dunes and rocky<br />

(syn. Tetragonia<br />

climbing spinach<br />

places, hangs where support<br />

implexicoma)<br />

available.<br />

Tetragonia tetragonioides NZ spinach C Shaded sea cliffs, coastal sands,<br />

dunes and stony beaches.<br />

Sedges, tussocks and grasses<br />

Austrostipa stipoides coastal needle tussock, MR, ME, MW, T Coastal rocks, cliffs, mud flats salt<br />

coastal immortality<br />

grass<br />

marsh fringes.<br />

Carex flagellifera MR, MT, ME, MW,<br />

TM<br />

Damp areas, open or forest margin.<br />

Carex lambertiana MR, W, TM Coastal forest, scrub and swamp.<br />

Cortaderia splendens + coastal toetoe TM, NG, ME? Coastal cliff faces and associated<br />

shrubland.<br />

Elymus multiflora blue wheat grass C, NG Coastal cliffs.<br />

Confirm if already present first.<br />

Uncinia uncinata hook grass MW, ME, W, MR,<br />

MT, TM<br />

Forest and scrub, swamp margins.<br />

16

Threatened species<br />

The Auckland region has at least 170 threatened plants, of which 70 species are recognised<br />

as a national conservation concern (Stanley, 1998). The decline in plant populations may be<br />

due to a combination of factors including animal browse, habitat loss, weed invasion, and<br />

the loss of native species which act as pollinators and seed-dispersers impairing regeneration.<br />

For many threatened plant species active management on pest-free islands is essential to<br />

increase the number of wild populations to ensure their long-term survival.<br />

Threatened plants most at risk from weeds are found in coastal habitats (foreshore and dune<br />

systems), damp habitats (wetlands and lakes), and seral plant habitats (disturbed and coastal<br />

areas) (Reid, 1998). These habitat types are particularly vulnerable to the invasion of weed<br />

species on the mainland, inhibiting germination and the establishment of native plant<br />

species. <strong>Motuora</strong> supports a range of representative habitats (coastal, damp and seral)<br />

suitable for the establishment of a range of endangered plants local to the Auckland Region.<br />

However these habitats are not weed free on <strong>Motuora</strong>, and weed management will be<br />

necessary in areas.<br />

In addition, there are a number of recognised risks associated with establishing some<br />

threatened plants in a modified environment not completely free of introduced pests. For<br />

example, coastal cresses (Lepidium oleraceum and Rorippa divaricata) are prone to attack by<br />

garden and crop Brassicaceae pests, being particularly affected by white rust. Other potential<br />

pests include cabbage white butterfly (Pieris repae), cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae),<br />

diamond-backed moth (Plutella xylostella), snails, slugs and various leaf miners (Norton & de<br />

Lange, 1999). Mawhai (Sicyos aff. australis) is susceptible to cucumber and zucchini mosaic<br />

virus. Risks associated with establishment of the threatened plants can be minimised through<br />

appropriate management as documented in the Department of Conservation individual<br />

species recovery plans (e.g. coastal cresses and pikao), and by liaising with specialist recovery<br />

groups including the Department of Conservation.<br />

Some of the threatened plants listed for introduction are reliant on disturbance events to<br />

maintain suitable stages of seral vegetation (e.g. shifting sand dunes, storm damage, and<br />

petrel burrowing disturbance) (Cameron, 2003). For example Pimelea tomentosa will require<br />

17

active management to maintain open sites with seral vegetation free of invasive species such<br />

as kikuyu grass (Pennisetum clandestinum) in order to establish self-sustaining populations. In<br />

contrast, New Zealand spinach (Tetragonia tetragonioides) is threatened by disturbance of<br />

coastal sands and stony beaches, requiring a more stable environment (NZPCN, 2003).<br />

Other potential risk factors include competition from invasive plants, loss of associated<br />

animals (e.g. seabirds), and substrate nutrient levels.<br />

On <strong>Motuora</strong> the aim will be to establish wild self-sustaining populations of threatened plants<br />

listed in Table 3. It is recognized that plant translocations are fraught with uncertainty and<br />

difficulties. An experimental approach will be used but even so it is possible that some of the<br />

species will not be established within the timeframe of this plan. The plants proposed for<br />

introduction have been recommended based on their vulnerability status (de Lange et al.,<br />

2004), habitat suitability and availability, their ecological, conservation and educational value,<br />

research potential, and management requirements (minimal with most species). It is<br />

recommended that the introductions are guided by individual species specific recovery plans<br />

developed by the Department of Conservation (Stanley, 1998).<br />

18

Table 3: Recommended Threatened And Uncommon Vascular <strong>Plan</strong>ts Suitable For<br />

Introduction Or Re-Introduction To The Following Habitats On <strong>Motuora</strong>.<br />

Key to species status (de Lange et al., 2004; Stanley, de Lange & Cameron, 2005):<br />

nc = Nationally critical (≤ 250 mature individuals) (47 spp.)<br />

ne = Nationally endangered (250-1000 mature individuals) (54 spp.)<br />

nv = Nationally vulnerable (1000-5000 mature individuals) (21 spp.)<br />

sd = Chronically threatened - serious decline (26 spp.)<br />

gd = Chronically threatened - gradual decline (70 spp.)<br />

sp = At risk - sparse (126 spp.)<br />

rr = At risk - range restricted (373 spp.)<br />

dd = Data deficient<br />

nt = Not threatened<br />

Botanical Common Status Potential source populations Habitat requirements and<br />

name name<br />

suitable planting sites<br />

Austrofestuca<br />

littoralis<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong><br />

(Bergin, 2000)<br />

Calystegia<br />

marginata<br />

Clianthus<br />

puniceus<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong><br />

(Shaw, 1993)<br />

Dactylanthus<br />

taylorii<br />

Reovery <strong>Plan</strong><br />

(DoC, 2005)<br />

Desmoschoenus<br />

spiralis<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong><br />

(Bergin &<br />

Herbert, 1998)<br />

Euphorbia<br />

glauca<br />

sand<br />

tussock,<br />

beach<br />

fescue,<br />

hinarepe<br />

smallflowered<br />

white<br />

bindweed<br />

kowhai<br />

ngutukak,<br />

kakabeak<br />

pua<br />

reinga,<br />

wood<br />

rose<br />

pikao,<br />

pingao,<br />

golden<br />

sand<br />

sedge<br />

shore<br />

spurge,<br />

waiuatua<br />

gd Pakiri Beach (Stanley, 2001)<br />

(Contact Christine Baines for<br />

permission to collect seed),<br />

Palmers Beach, Great Barrier<br />

Island (Cameron, 1999b)<br />

sp Ti Point (contact Maureen Young<br />

for site location) (grows easily from<br />

seed)<br />

nc Moturemu, Kaipara Harbour,<br />

Tiritiri Matangi<br />

Stable sand dunes under<br />

pohutukawa amongst Calystegia<br />

soldanella and Spinifex sericeus.<br />

Still Bay and Home Bay<br />

Open shrublands, coastal<br />

headlands, rough pasture and<br />

adjacent track margins.<br />

Scrambler<br />

Bluffs, coastal cliffs, lake<br />

margins and successional<br />

habitats. Short coastal scrub,<br />

open or partially open. Twin<br />

dams and coastal cliffs.<br />

sd Little Barrier Root parasite of mahoe, fivefinger,<br />

kapuka, karamu,<br />

mapou, hangehange and<br />

putaputaweta<br />

gd Mahurangi West, historically<br />

present Kawau Is (Buchanan,<br />

1876)<br />

sd Browns Island (Gardner, 1996),<br />

Little Barrier Island,<br />

Motuhoropapa, Noises Island<br />

group (Atkinson, 1960b)<br />

Coastal sand dunes, sloping<br />

unstable surfaces, Home Bay<br />

Coastal cliffs, rocky bluffs,<br />

mudstone slopes and sand<br />

dunes, Still Bay<br />

19

Geranium<br />

solanderi “large<br />

petals”<br />

Ileostylus<br />

micranthus<br />

National<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong><br />

(Cameron,<br />

2000)<br />

Lepidium<br />

flexicaule<br />

Lepidium<br />

oleraceum<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong><br />

(Norton & de<br />

Lange, 1999)<br />

Historically<br />

present on<br />

Kawau,<br />

Rangitoto<br />

Island<br />

native<br />

geranium,<br />

turniprooted<br />

geranium<br />

green<br />

mistletoe<br />

coastal<br />

cress<br />

Cooks’s<br />

scurvy<br />

grass<br />

Picris burbidgeae native<br />

oxtongue<br />

Pimelia<br />

tomentosa<br />

Pisonia<br />

brunoniana<br />

Rorippa<br />

divaricata<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong><br />

(Norton & de<br />

Lange, 1999)<br />

status? Casnell Island (de Lange &<br />

Crowcroft, 1996), Tiritiri Matangi<br />

(Cameron & West, 1985-86) ,<br />

Pudding Island (Cameron &<br />

Taylor, 1992), Motuihe Island (de<br />

Lange & Crowcroft, 1999), Noises<br />

Islands group (Cameron, 1998)<br />

nt Mahurangi West roadside,<br />

proposed bypass, Warkworth<br />

nv South Taranaki coast (2003),<br />

historical records Auckland,<br />

Recovery <strong>Plan</strong> (Norton & de<br />

Lange, 1999)<br />

ne Little Barrier, Great Barrier islets,<br />

Mahuki Is GB (contact Hilary<br />

McGregor DoC and Steve Benham<br />

ARC), northern offshore islands,<br />

(grows easily from seed and semihardwood<br />

cuttings)<br />

ne Casnell (Maunganui) Island (de<br />

Lange & Crowcroft, 1996),<br />

Mokohinau and Hen & Chicken<br />

Islands, Great Barrier (western<br />

side), (seed available from Oratia<br />

<strong>Native</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>t Nursery)<br />

sd Goat Island, Waiheke, Great<br />

Barrier (Cameron, 2003), Woodhill<br />

forest<br />

parapara sp Mangawhai (Stanley & de Lange,<br />

2005) (grows easily from seed)<br />

NZ<br />

watercress<br />

ne Fanal Island, Mokohinau group,<br />

seed available from Oratia <strong>Native</strong><br />

<strong>Plan</strong>t Nursery<br />

Dry open lowland<br />

Coastal and lowland forest<br />

Hosts totara, kanuka, Coprosma<br />

propinqua, manuka, mapou<br />

Coastal turfs, rock stacks,<br />

outcrops, headlands, cliff faces<br />

and boulders<br />

Seabird roosts and nesting<br />

sites, fertile soils on coastal<br />

slopes, rocky shorelines and<br />

gravel beaches. Between Rocky<br />

Bay and Still Bay around petrel<br />

burrows. Home Bay and<br />

Macrocarpa Bay (non-sea birds<br />

sites).<br />

Scrub and cliff margins.<br />

Eastern cliffs of the island.<br />

Coastal and semi-coastal<br />

forest. Open grassy cliff tops,<br />

in scrub and seral habitats. On<br />

the slopes around the Kiwi<br />

track.<br />

Sheltered understorey of<br />

mixed-broadleaf forest.<br />

Tolerant of exposed sunny<br />

conditions.<br />

A coloniser of disturbed<br />

ground, petrel burrows, recent<br />

slips, track margins. <strong>Plan</strong>ts<br />

often grow around burrow<br />

entrances. Grows best in<br />

dappled light, and is often<br />

found in forested habitats<br />

20

Senecio<br />

scaberulus<br />

Sicyos aff.<br />

australis<br />

Streblus<br />

banksii<br />

Tetragonia<br />

tetragonioides<br />

Tupeia<br />

antarctica<br />

fireweed ne Goat Island (DoC),<br />

Noises Islands group (Cameron,<br />

1998)<br />

native<br />

cucumber,<br />

mawhai<br />

large-leaved<br />

milk tree<br />

NZ spinach<br />

kokihi<br />

green<br />

mistletoe<br />

taapia<br />

dd Great Barrier islets, Motuhaku<br />

Wellington Head, Historically<br />

present Kawau Is (Buchanan,<br />

1876), Moutihe Is (Kirk, 1878),<br />

Noises Islands group (Cameron,<br />

1998, Mason & Trevarthen,<br />

1950)<br />

sp Mahurangi East and<br />

Wenderholm? Tawharanui,<br />

Waiwera, Great Barrier Island<br />

sp Casnell Island, Mahurangi<br />

Harbour (de Lange & Crowcroft,<br />

1996). Recommended to collect<br />

seed from adjacent mainland (B.<br />

Stanley, pers. comm.)<br />

gd Fanal Island, Mokohinau Islands<br />

(Stanley, 2004), Kawau Is<br />

(Buchanan, 1876)<br />

Cliffs, coastal scrub, forest margins<br />

and clearings. Shaded sites amongst<br />

short grasses under coastal<br />

pohutukawa forest or short scrub,<br />

cliffs and banks near the sea, rocky<br />

outcrops and inland in canopy gaps.<br />

Pohutukawa Bay.<br />

Coastal and lowland forest, scrub and<br />

amongst bracken fern in shade.<br />

Coastal forest. Requires male and<br />

female<br />

Open coastal sites, sand dunes and<br />

stony beaches.<br />

High light, regenerating shrubland,<br />

forest edges and roadsides. Hosts<br />

include Pittosporum species,<br />

putaputaweta (Carpodetus serrata),<br />

Coprosma species, five-finger<br />

(Pseudopanax arboreus), white maire<br />

(Nestegis lanceolata) and coastal maire<br />

(Nestegis apetala)<br />

Monitoring Requirements<br />

It is recommended that long-term monitoring plots representative of each area planted<br />

annually are set up to measure successional changes in the composition and abundance of<br />

plants and the recruitment of invertebrates and lizards. Indicator species could be used to<br />

measure change wherever possible. Additional photo points for new plantings should be<br />

identified. A flora survey should be conducted in 2017 to identify species abundance,<br />

distribution and recruitment. Specialist interest groups that could facilitate monitoring<br />

programmes in conjunction with the <strong>Motuora</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Society include threatened plant<br />

recovery groups, Auckland Botanical Society, Auckland Botanical Gardens, Department of<br />

Conservation, universities and Forest and Bird.<br />

21

The establishment of threatened plant populations should be monitored. Monitoring plans<br />

for threatened species are outlined in individual species Recovery <strong>Plan</strong>s. It is also<br />

recommended that support is sought from the Department of Conservation’s threatened<br />

plant specialist to develop site specific monitoring plans for each species.<br />

22

Section Three: <strong>Restoration</strong> of <strong>Motuora</strong>’s Invertebrate Fauna<br />

Current Situation<br />

Most information available on the <strong>Motuora</strong> invertebrate fauna comes from a survey carried<br />

out during the summer of 2003/4 (see Appendix 10 for details). In numerical terms, the<br />

survey sample was dominated by two orders: mites (Class Arachnida; Order Acarina) and<br />

springtails (Class Insecta; Order Collembola). However as mites and springtails are all very<br />

small they contributed little in terms of biomass. The dominant orders in terms of biomass<br />

were landhoppers (Class Malacostraca; Order Amphipoda), slaters (Class Malacostraca;<br />

Order Isopoda), and three insect orders; beetles (Order Coleoptera), bees/ants/wasps<br />

(Order Hymenoptera) and weta/crickets (Order Orthoptera). The orders recorded were<br />

typical for the type of trapping utilized and no major orders were absent from <strong>Motuora</strong>.<br />

The survey results suggested that invertebrate abundance in naturally regenerating forest was<br />

higher on <strong>Motuora</strong> than on other modified offshore islands, due mainly to the high number<br />

of beetles recorded on <strong>Motuora</strong> (R.Gardner-Gee, unpub. data, Moeed & Meads 1984; 1987).<br />

There are several possible explanations for the differences between <strong>Motuora</strong> and the other<br />

offshore islands. Reduced predation on <strong>Motuora</strong> (due to the lack of mammalian predators<br />

and reduced diversity and abundance of native predators such as reptiles) may result in<br />

increased numbers of invertebrates, and especially increased numbers of larger bodied<br />

invertebrates such as ground weta and carabid beetles (Hutcheson, 2000; Ramsay, 1978).<br />

Alternatively, differences may be due to other factors, such as climate variation, variation in<br />

seabird abundances between islands (areas with nesting seabirds often have high invertebrate<br />

abundances) or variation in disturbance histories between islands.<br />

The survey also indicated that invertebrate abundance and composition varied between<br />

vegetation types within <strong>Motuora</strong>. The invertebrate fauna in planted areas on <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

differed markedly from the invertebrate fauna in older areas of naturally regenerating forest<br />

on the island and also differed from the invertebrate fauna in pasture. Most of the difference<br />

is due to the high numbers of landhoppers and slaters in the planted areas. It is likely that<br />

these differences are due to the disturbance associated with planting and the young age of<br />

the planted forest (D. Ward unpub. data; Jansen, 1997).<br />

23

Beetles deserve special mention because on <strong>Motuora</strong> they have been studied in more detail<br />

than any other group. The 2003/4 survey collected a total of 153 beetle species. Of these, 96<br />

species (63%) are native to New Zealand, 45 species (29%) are introduced and 12 species<br />

(8%) are of unknown origin (Gardner-Gee, 2004). Many of the beetle species that occur on<br />

<strong>Motuora</strong> also occur at other modified coastal forest sites (Clarke, 2003; Kuschel, 1990) and<br />

none of the <strong>Motuora</strong> species are endemic to the island or listed as endangered (McGuinness,<br />

2001). The naturally regenerating forest areas on <strong>Motuora</strong> have a reasonably diverse beetle<br />

fauna with a high proportion of native beetle species and some flightless and specialist<br />

species (Gardner-Gee, 2004). A mobile, generalist subset of this forest fauna has established<br />

in the planted areas, creating an early succession beetle assemblage (Gardner-Gee, 2004).<br />

The Original Invertebrate Fauna of <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

Detailed reconstruction of the original <strong>Motuora</strong> invertebrate fauna is not possible due to a<br />

lack of both paleological information and suitable benchmark islands. <strong>Motuora</strong> has<br />

experienced considerable human disturbance and it is likely that some invertebrate species<br />

have been lost from the island. The absence of introduced mammalian predators may<br />

however have enabled at least some of the original invertebrate fauna to survive the forest<br />

clearance. For example, two beetle species Ctenognathus novaevelandiae (Carabidae) and<br />

Mimopeus elongatus (Tenebrionidae) are vulnerable to rat predation and have been lost from<br />

many rat-infested northern offshore islands (Watt, 1986). Both species persist on <strong>Motuora</strong><br />

(Gardner-Gee, 2004). Velvet worms (Phylum Onychophora) also still survive on <strong>Motuora</strong>:<br />

an undescribed species of Ooperipatellus was collected on the island in 2005 (R. Gardner-Gee,<br />