Introduction

Tetanus is an acute and serious infection caused by toxin-producing bacteria named Clostridium tetani. It was first described in Egypt over 3000 years ago and is still prevalent in the developed world as a major health problem. When the bacterial spores enter deep into the body, they produce a toxin that results in painful spasms in the muscles. The first sign is spasms of the jaw muscles which is also called “lockjaw”. The muscles of the neck and jaw can tighten, making it difficult to swallow and requiring medical attention.

Incidence

- A worldwide study done during 2000–2018, revealed that the estimated number of Neonatal Tetanus (NT) deaths decreased by 85% (Njuguna, Yusuf, Raza, Ahmed, & Tohme, 2020).

- During 2000–2018, 45 countries achieved Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus (MNT) elimination, reported that NT cases decreased by 90%, and estimated deaths declined by b85%.

Causes of Tetanus

- Tetanus is a bacterial infection caused by anaerobic bacteria named C. tetani.

- The bacteria produce spores that are most commonly present in soil and dirt but can also be found in the dust and intestines of various animals in the surrounding environment.

- The spores are inactive when they are outside the living body but can remain infectious for more than 4 decades.

- The spores are immensely hard and are resistant to various antiseptics, and heat, and even viable after boiling for several minutes.

- If the spores of C. tetani enter the bloodstream of a mammal, they can become active again and start infecting the individual.

- Humans of all age groups can get tetanus but it is usually more common and serious in newborn babies and their mothers when the mother is not protected from tetanus by the vaccine.

Predisposing Factors

- Open skin (wound, small laceration, skin breaks, insect or dog bites, surgical procedures, fractures, gangrene)

- Immunosuppressed people

- Lack of tetanus immunization or partially immunized

- Risk factors for neonatal tetanus

- Home delivery

- Neonatal tetanus in a previous child

- Unvaccinated mother

- Infectious substances applied to the umbilical stump, e.g., mud, animal dung, etc.

- Septic cutting of the umbilical cord

Incubation Period

- The average incubation period of tetanus is 8 days in average, ranging from 3 to 21 days.

- However, depending on the type and severity of the wound, the incubation period can be as short as 1 day or as long as several months.

- Most cases tend to occur within 14 days.

Mode of Transmission

- Tetanus does not transmit from human to human.

- Spores of the C. tetani are found anywhere in the environment like dirt, manure, and dust.

- The spores enter the body through cuts, wounds, or any opening in the skin and develop into bacteria.

Forms and Signs and Symptoms of Tetanus

Based on the clinical features, there are the following forms of tetanus.

Generalized tetanus

It is the most common form. The presenting symptoms include

- Lockjaw (trismus: inability to suck),

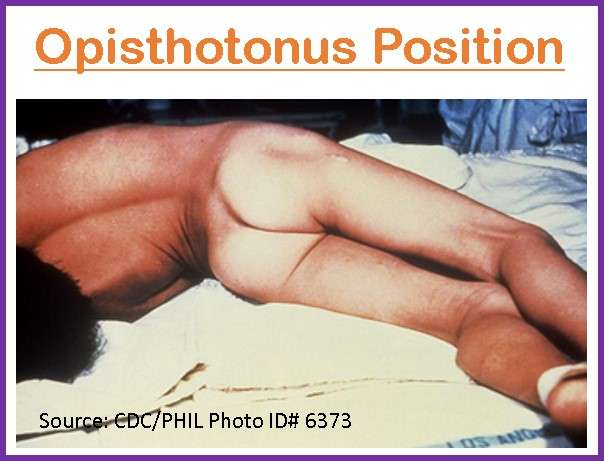

- Opisthotonus (abnormal posture where the back becomes extremely arched due to muscle spasms),

- Risus sardonicus (facial grimacing),

- Spasms,

- Muscle rigidity,

- Back and neck stiffness,

- Dysphagia, and restlessness.

- Reflex spasms are triggered by minor external stimuli such as light, noise, or touch.

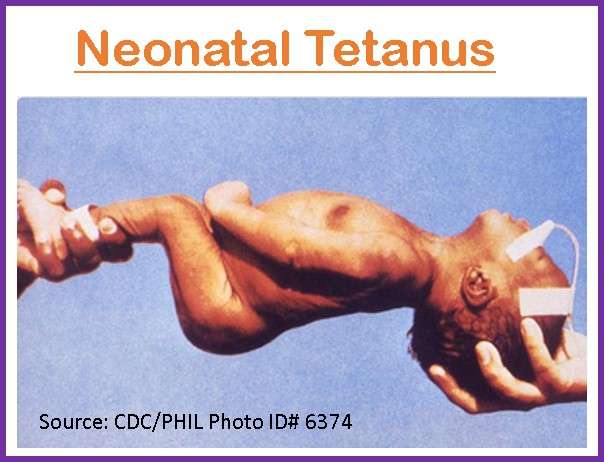

Tetanus neonatorum

It is a generalized form of tetanus seen in newborns that are previously well and feeding normally. The newborn presents with symptoms of

- Irritability,

- Inability to suck,

- Muscle rigidity,

- Opisthotonos,

- Risus sardonicus and

- Severe spasms triggered by sound, light, and sensory stimuli within the first 28 days of life.

Localized tetanus

- It is a rare presentation localized at the site of spore entry (injured site), with weakness of the involved extremity and intense, painful spasms in severe cases.

- It can progress to the more life-threatening generalized form.

Cephalic tetanus

- It is the result of inoculation of spores via head injury or middle ear infection and presents as motor cranial nerve palsies that commonly affect the facial nerve. It manifests with

- Dysphagia,

- Trismus

- Neck stiffness

- Retracted eyelids,

- Deviated gaze

- Risus sardonicus

Maternal tetanus

- It occurs during pregnancy or within 6 weeks of delivery which develops in unimmunized women having unsafe abortions or unclean deliveries.

Other symptoms

- Irritability,

- Excessive sweating,

- Fever,

- Drooling,

- Hand or foot spasms,

- Swallowing difficulty,

- Uncontrolled urination or defecation etc.

Pathophysiology of Tetanus

- The bacteria (Clostridium tetani) enter the human body through a contaminated wound or an umbilical stump (in neonatal tetanus) or by contact with contaminated medical instruments.

- The spores germinate in the wound because of their anaerobic character.

- Then toxins are produced and spread through the blood and lymphatic system.

- Two exotoxins are produced:

- Tetanolysin is a hemolysin but its pathology is unknown in tetanus.

- Tetanospasmin is a neurotoxin responsible for the spasticity associated with tetanus and is the most potent toxin known to humans.

- The toxin uses a retrograde path along the nerve axon to reach the spinal cord and the brainstem.

- The toxin then binds with the receptors and the process is irreversible.

- The toxin divides the membrane proteins (SNARE proteins) that are responsible for the expulsion of inhibitory neurotransmitters at the neuronal synapses.

- The disinhibiting of upper motor neurons affects the lower motor neurons that are responsible for carrying motor cortex excitatory impulses affecting the autonomic neurons and the anterior horn cells.

- The disinhibiting involving anterior horn cells leads to an unopposed contraction of the muscles, leading to excessive tone and muscle spasms that can be painful.

- Disinhibiting the autonomic nervous system can lead to seizures.

- Neonatal tetanus develops quickly (within hours) due to the shorter length of the axons.

Diagnosis of Tetanus

- Clinical evaluation: Diagnosis is done based on clinical features and does not require laboratory confirmation.

- Confirmed neonatal tetanus: It is an illness seen in an infant who has a normal sucking ability and a good cry in the first 2 days of life but loses these abilities between 3 and 28 days of life and has spasms followed by trismus and stiffness.

- Non-neonatal tetanus: It requires a sustained spasm of the facial muscles in which the person appears to be grinning (Risus sardonicus) or painful muscular contractions. Although a person usually has a history of injury, burn, or wound, it may also occur in those who do not give a history of a specific wound or injury.

- Can be differentiated from meningoencephalitis due to intact sensorium, normal cerebrospinal fluid, and muscle spasms in Tetanus.

- C. tetani can sometimes be cultured from the wound but is not very sensitive; only 30% of patients with tetanus have positive cultures. Also, false-positive cultures can be seen in patients without tetanus.

Treatment of Tetanus

Supportive Care

- Tetanus toxin cannot be removed from the nervous system once attached to neurons. Thus, supportive care is the mainstay of treatment.

- Prolonged immobility is common in patients with severe tetanus, admitted to the intensive care unit and on mechanical ventilation. Other complications like nosocomial infections, decubitus ulcers, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, thromboembolic disease, tracheal stenosis, etc. may also be seen.

- Early tracheostomy is indicated for prolonged mechanical ventilation, better tracheal suctioning, and pulmonary hygiene.

- Early nutritional support is mandatory for extremely high energy demands. Enteral feeding is preferred. Prophylactic treatment is given to prevent gastro-esophageal hemorrhage from stress ulceration.

- Unfractionated Heparin, low molecular weight heparin, or other anticoagulants are given early for prophylaxis of thromboembolism.

- Since patients often have a disability from prolonged muscle wasting and contractures Physical therapy should be started as soon as spasms have ceased.

- In the absence of an ICU, a separate ward or room should be provided for the patients and sensory stimuli (loud noises, physical contact, and light) should be kept to a minimum since they can trigger tetanic spasms. Eye shades and ear plugs also help to reduce stimuli.

- Paralytic agents such as vecuronium, pancuronium, etc. are used with ventilator support.

- To avoid respiratory depression, benzodiazepines and baclofen can be administered in nonventilated cases if doses are carefully titrated.

- Magnesium sulfate is given to control rigidity and mild spasms as well as to manage autonomic dysfunction.

Wound Debridement

- Wound debridement is done in all patients with tetanus to eradicate spores and necrotic tissue, which could lead to a favorable environment for germination.

Tetanus Antitoxin

- The use of antitoxin (passive immunization) to neutralize unbound toxins is associated with improved survival and standard of care.

- Intramuscular antitoxin: Human tetanus immune globulin (HTIG) is the antitoxin of choice to neutralize the unbound toxin and is given in a single dose of 500 units. HTIG should be given as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, with part of the dose infiltrated around the wound. But it is given at different sites than tetanus toxoid.

- If HTIG is not available intramuscular or intravenous equine antitoxin is a reasonable alternative.

- If HTIG or equine antitoxin is not available, intravenous immune globulin may be administered.

- Active immunization: Since tetanus does not provide immunity following recovery from acute illness, all patients with this disease should receive active immunization in a full series.

Control of Muscle Spasms

- Generalized muscle spasms are life-threatening because they can lead to respiratory failure, aspiration, and generalized exhaustion in the patient.

- Several drugs are used to control the spasms.

- Benzodiazepines (Diazepam, Midazolam)

- Sedatives

- Care is provided to the placement of the patient and control of light or noise in the room to avoid provoking muscle spasms.

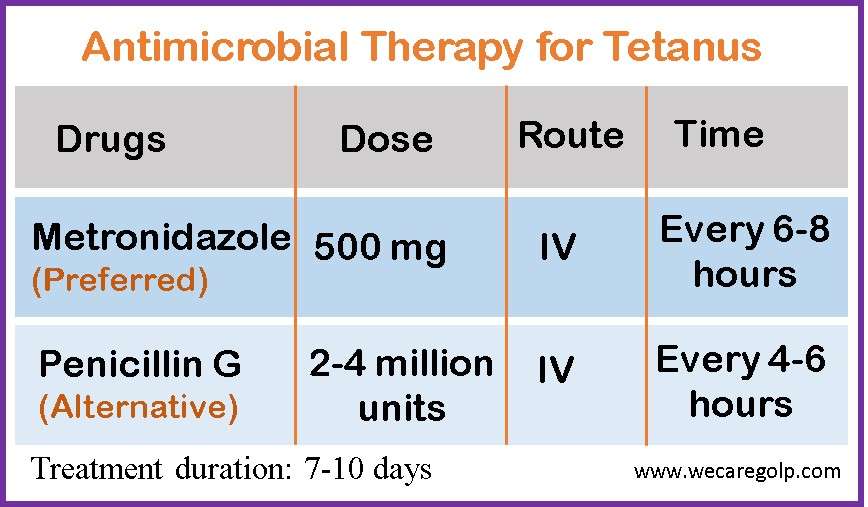

Antimicrobial Therapy

Appropriate antimicrobial therapy may fail to eradicate the bacteria unless wound debridement is done.

Management of Autonomic Dysfunction

- Magnesium helps in reducing muscle spasms.

- Labetalol is given because of its dual alpha- and beta-blocking properties.

- Morphine sulfate 0.5 to 1 mg/kg per hour by continuous IV (intravenous) infusion

- Other drugs used for the treatment of various autonomic events are

- Dexmedetomidine

- Atropine

- Clonidine

- Epidural bupivacaine.

Complications

- Airway obstruction /Laryngospasm

- Respiratory arrest

- Pulmonary embolism

- Heart failure

- Aspiration Pneumonia

- Damage to muscles

- Fractures

- Brain damage as a result of oxygen deprivation during spasms

Prevention of Tetanus

Vaccination

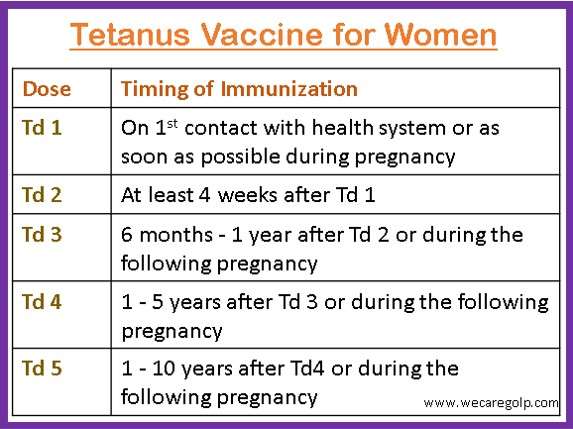

Tetanus-toxoid-containing vaccines (TTCV) are included in routine immunization programs all over the world for the prevention.

- The vaccines are given during antenatal care.

- Neonatal tetanus can be prevented by providing TTCV to women of reproductive age.

- Women should receive at least 2 doses of TTCV during pregnancy and can continue further doses after pregnancy or in subsequent pregnancies.

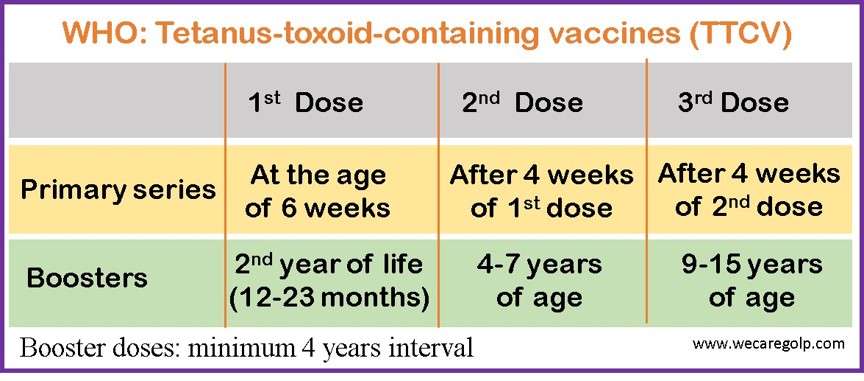

World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that a person should receive 6 doses (3 primary and 3 booster doses) of TTCV for lifelong protection.

There are many kinds of vaccines used to protect against tetanus, combined with vaccines for other diseases.

- Diphtheria and tetanus (DT) vaccines

- Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (whooping cough) (DTaP) vaccines

- Tetanus and diphtheria (Td) vaccines

- Tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccines

Medical practices can also prevent tetanus disease including clean delivery and cord care during childbirth, and proper wound care for injuries, burn, and surgical and dental procedures.

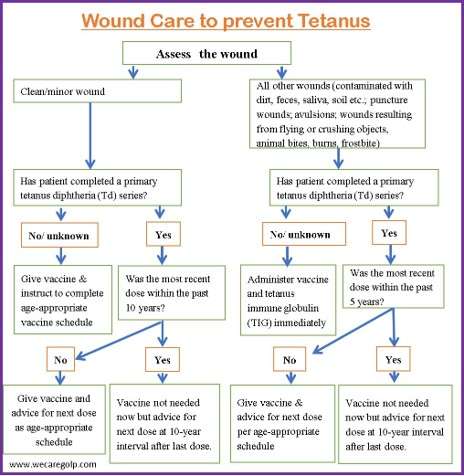

Wound Care and Tetanus Prophylaxis

Prognosis

- Tetanus may be a fatal disease, and its mortality rate has been reported to be around 35%, with a higher fatality rate in hospitals that do not have proper intensive care facilities.

- Generally shorter intervals indicate more severe tetanus with a poorer prognosis.

- Patients who survive tetanus may return to their previous state of health but the recovery is slow and usually occurs over 2-4 months.

- Some patients may also have complications.

Summary

- Tetanus is a severe acute bacterial infection caused by C. tetani which are found in dirt, soil, and excreta of human and animals.

- There is no human-to-human transmission of the infection.

- The bacilli enter the body through a wound and produce toxins.

- The symptoms are seen when the toxins act on the central nervous system.

- Diagnosis is based on the signs and symptoms of the disease.

- The vaccine can completely prevent the disease.

- A high fatality rate is seen in health centers having improper Intensive care facilities.

References

- Njuguna, H. N., Yusuf, N., Raza, A. A., Ahmed, B., & Tohme, R. A. (2020, May 1). Progress Toward Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination – Worldwide, 2000-2018. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 69(17), 515-520. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6917a2

- Thwaites, C. L., Beeching, N. J., & Newton, C. R. (2015, Jan 24). Maternal and neonatal tetanus. Lancet (London, England), 385(9965), 362-375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60236-1

- Farrar, J. J., Yen, L.M., Cook, T., Fairweather, N., Binh, N., Parry, J., Parry, C. M. (2000, Sep). Tetanus. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 69(3)292-301. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp.69.3.292

- Holm, G. (2018, Sep 29). Tetanus (Lockjaw). Healthline. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 6 from https://www.healthline.com/health/tetanus

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Division of Bacterial Diseases (2022, Aug 22). Tetanus. CDC. Retrieved on 2023, Feb 5 from https://www.cdc.gov/tetanus/