ANIMALS IN SEA HISTORY

Kiore Rat

By Richard King

Charles Darwin only spent nine days in New Zealand during his famous voyage aboard HMS Beagle. He learned firsthand that these islands had no native mammals. Large, flightless birds, such as the enormous moa and the turkey-sized, multi-colored takahe had, Darwin believed, “replaced” the roles of any native mammals.

On the day before Christmas 1834, feeling a little homesick, Darwin made a now-fascinating observation about the rodents he encountered ashore. Writing a short description that has a great deal of meaning today, Darwin wrote: “It is said that the common Norway rat, in the short space of two years, annihilated in this northern end of the island, the New Zealand species [of rat]. In many places I noticed several sorts of weeds, which, like the rats, I was forced to own as countrymen.”

Darwin understood that the Norway rat and the weeds he observed growing along the Bay of Islands in New

Zealand had been introduced by British ships. Rats—the Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus) and the Ship rat (Rattus rattus)—along with a variety of plants, had been unintentionally carried across the oceans by ships delivering missionaries and supplies to New Zealand, while harvesting flax and trees to bring home. American, British, and French whalers and sealers also surely accidentally introduced these species as well.

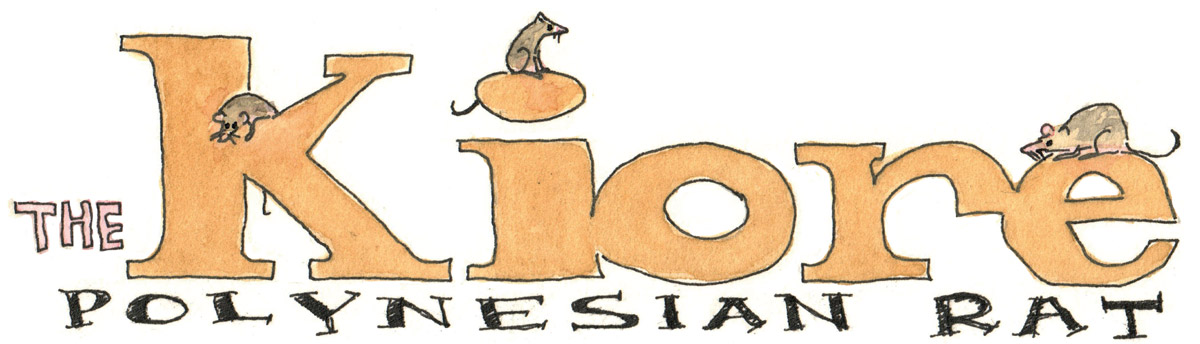

What Darwin did not learn during his short stay is that the “New Zealand species” of rat he noted was not indigenous to this part of the world at all. This type of rat, which is much smaller than the other two and with a lighter brown fur, was known to the Maori as kiore; today it is also known as the Polynesian or Pacific rat (Rattus exulans). More than 800 years ago, the kiore came to this part of the world aboard the double-hulled sailing canoes of the Polynesians, during their epic migrations across the Pacific. The Polynesians, who settled in New Zealand in various tribes called iwi, brought the rats with them as pets, but also as a food source; their tiny pelts were also sometimes stitched together to make cloaks for men and women of high standing. Sometimes kiore were fed with berries, grilled, and then preserved in fat and served as a delicacy. Recently, ecologists and archaeologists have used kiore bones and their DNA, including that taken from the rats’ fossilized poop, to help piece together the timing and locations of the historical migrations of Polynesian people to New Zealand and throughout the Pacific.

Long before Darwin’s visit, this Polynesian rat had been doing serious damage to some of the native birdlife. The populations of New Zealand’s large flightless birds—such as the now-extinct moa, the now-endangered flightless parrot called the kakapo, and the iconic kiwi—were not only diminished by human hunting, but also by the kiore, which feasted on the eggs and even the chicks of these ground-nesting birds, which had never evolved any defenses against these kinds of mammals—or against any mammals. Kiore also ate a range of other unique species in New Zealand, including lizards, flightless beetles, and the giant weta, a kind of insect. Then, as Darwin accurately observed, when the Norway and ship rats arrived in the late 1700s, they so outcompeted kiore that not long after Darwin’s visit to the region in the 1830s, the Polynesian rat was isolated to only a few locations in the South Island and on some of the coastal islands.

Long before Darwin’s visit, this Polynesian rat had been doing serious damage to some of the native birdlife. The populations of New Zealand’s large flightless birds—such as the now-extinct moa, the now-endangered flightless parrot called the kakapo, and the iconic kiwi—were not only diminished by human hunting, but also by the kiore, which feasted on the eggs and even the chicks of these ground-nesting birds, which had never evolved any defenses against these kinds of mammals—or against any mammals. Kiore also ate a range of other unique species in New Zealand, including lizards, flightless beetles, and the giant weta, a kind of insect. Then, as Darwin accurately observed, when the Norway and ship rats arrived in the late 1700s, they so outcompeted kiore that not long after Darwin’s visit to the region in the 1830s, the Polynesian rat was isolated to only a few locations in the South Island and on some of the coastal islands.

An illustration of the Polynesian Rat, published as part of a scientific paper titled, “On the New Zealand Rat,” by Walter Buller in 1870.

Today, the New Zealand government has set a goal known as “Predator-Free 2050,” in which it is attempting to remove all three species of rats and other invasive mammals, such as possums and stoats, to try to protect their native endangered birds. But due to the sacred connection that some Māori in the North Island have maintained with the kiore, considering them a taonga, or treasure, and an ancestral friend of the first voyagers, small populations of the kiore have been moved from areas where they have damaged specific bird populations to other islands where they will do less harm under the management of local iwi in the same way Māori had done hundreds, if not thousands, of years ago, managing their kiore in specially-monitored reserves.

A 19th-century Tawhiti makamaka, or portable rat trap. The Māori prized the kiore and established reserves for them to control how and when the animals were harvested. Hunting and trapping kiore occurred in highly organized events. The specially prepared meat was often reserved for important guests and tribal leaders.

Back in 1834, Darwin did not spend enough time there to learn how much these “New Zealand rats” had been revered—and he only had an inkling as to how much influence they had had on the ecology of New Zealand. Darwin visited during some of the most rapid and impactful decades of environmental change in New Zealand, an archipelago that is as unique in its isolation as those Galápagos Islands of his.

For more “Animals in Sea History” go to Sea History for Kids’ Animals section or educators.mysticseaport.org.

Did You Know?

Today, nearly 42,000 men and women serve on active duty in the US Coast Guard.

The United States Coast Guard is the nation’s oldest maritime service and is really a combination of five different agencies that were brought together to make them run more efficiently—the Revenue Cutter Service, the Lighthouse Service, the Life-Saving Service, the Bureau of Navigation, and the Steamboat Inspection Service.

What do members of the Coast Guard do every day?