Yesterday Marla and I joined our friend Wendy for a two-tank dive trip with Kohala Divers. As usual, the KD staff was excellent and the dive sites were great. The only trouble was that there were too many passengers with cameras. Due to the virtual absence of tourists on the island these days there were only nine paying divers on the boat, but at least six of them, including Wendy and me, were toting cameras. With that many photographers in the water, sighting of an interesting fish can result in something resembling a rugby scrum—everyone muscling in for a good shot before the poor, terrified fish bolts. It seems like the people with the biggest, most expensive photo rigs are the worst. I guess they figure that we peons with smaller, less expensive setups will never be able to take a good photo anyway, so what the heck. Wendy and I, with our modest cameras, and our senses of civility, tended to hang back. (Marla is wise enough to not mar the experience of enjoying the fish by carrying a camera at all.)

Kohala Divers, like most West Hawaii operators, tries to mitigate this situation by sending divers down in small groups—in this case one group of four and one of five divers. This helps, but sometimes, especially if an unusually uncommon fish is sighted, the groups will converge.

That said, it was a great couple of dives, with lots of interesting fish at both dive sites. And don’t mind my kvetching—we all had a great time.

Almost immediately on our descent at the first site (Black Point) we spotted this Bandit Angelfish. This endemic species is uncommon to rare here on the Big Island, and neither Marla, Wendy, nor I had ever seen one before. By time I waited out the initial scrum the fish had had enough of us and started moving off. I got this parting shot.

We came across a handful of Ewa Fang Blennies—also endemic. Not particularly uncommon, but so pretty. This one is joined by one of the ubiquitous Gold-ring Surgeonfish.

We came across this Tiger Snake Moray on the second dive at a site called Black Point Caves. Marla and I had only seen this species once before—sans camera. John Hoover calls it secretive and nocturnal rather than particularly uncommon. He also informs us that the species preys primarily on other eels.

A Potter’s Angelfish popped its head out while I was trying to photograph the snake moray. We also saw, but did not photograph, a Flame Angel, and I briefly spotted a Fisher’s Angel. That makes all four of the angelfish species one has any likelihood of running into in the main Hawaiian Islands.

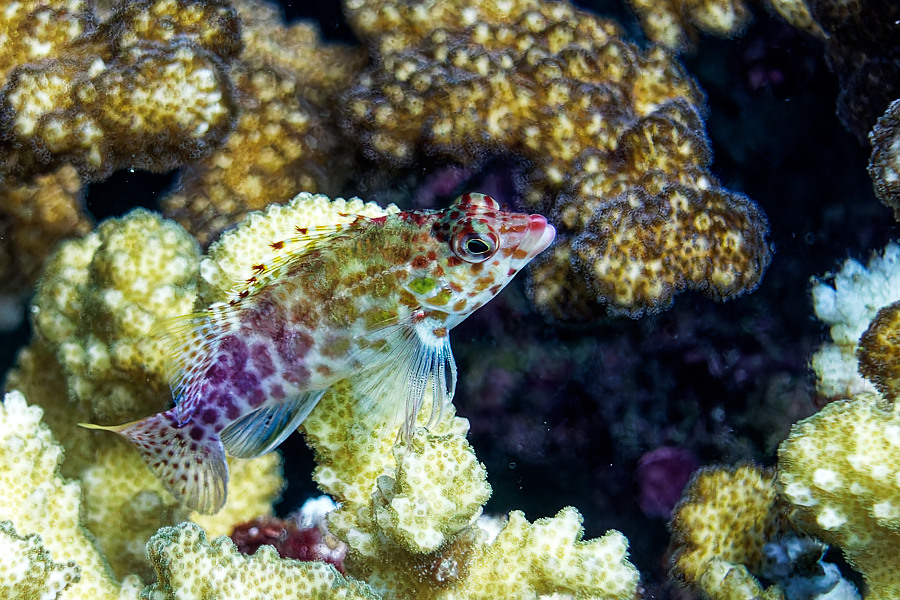

This one was a heartbreaker for me. I’d been wanting to see and photograph a Longnose Hawkfish—a fish that Hoover calls “an unusual find in the Islands”— for several years, but have never encountered one until yesterday’s dive. Once again I was late to the show—the fish bolted right after my arrival and this was the only shot I managed. Oh well, better luck next time. (Don’t you love that plaid pattern?)

So, yeah, a really great trip. I was buzzed for the rest of the day. Maybe I should be more like Marla and just enjoy the dive instead of getting so wrapped up in the goal of acquiring photos. Maybe one day, but for now it’s a fun (okay, a bit expensive, too) way to exercise my inner hunter-gatherer.