I needed to be in the woods for a while so I chose Yale Forest in Swanzey. The forest is owned by Yale University and is where the students in the forestry program get some hands on experience.

The trail used to be one of the roads north into Keene and you can still see pavement here and there.

The beeches and oaks were still hanging on so there was some fall color to enjoy.

There was also still some snow left from the first snow storm that dropped about 4 inches. First snows almost always melt away because the ground hasn’t yet frozen.

Evergreen ferns don’t mind snow. In fact they’ll stay green even under feet of it. That’s an evergreen Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides) on the right and a spinulose wood fern (Dryopteris carthusiana) on the left.

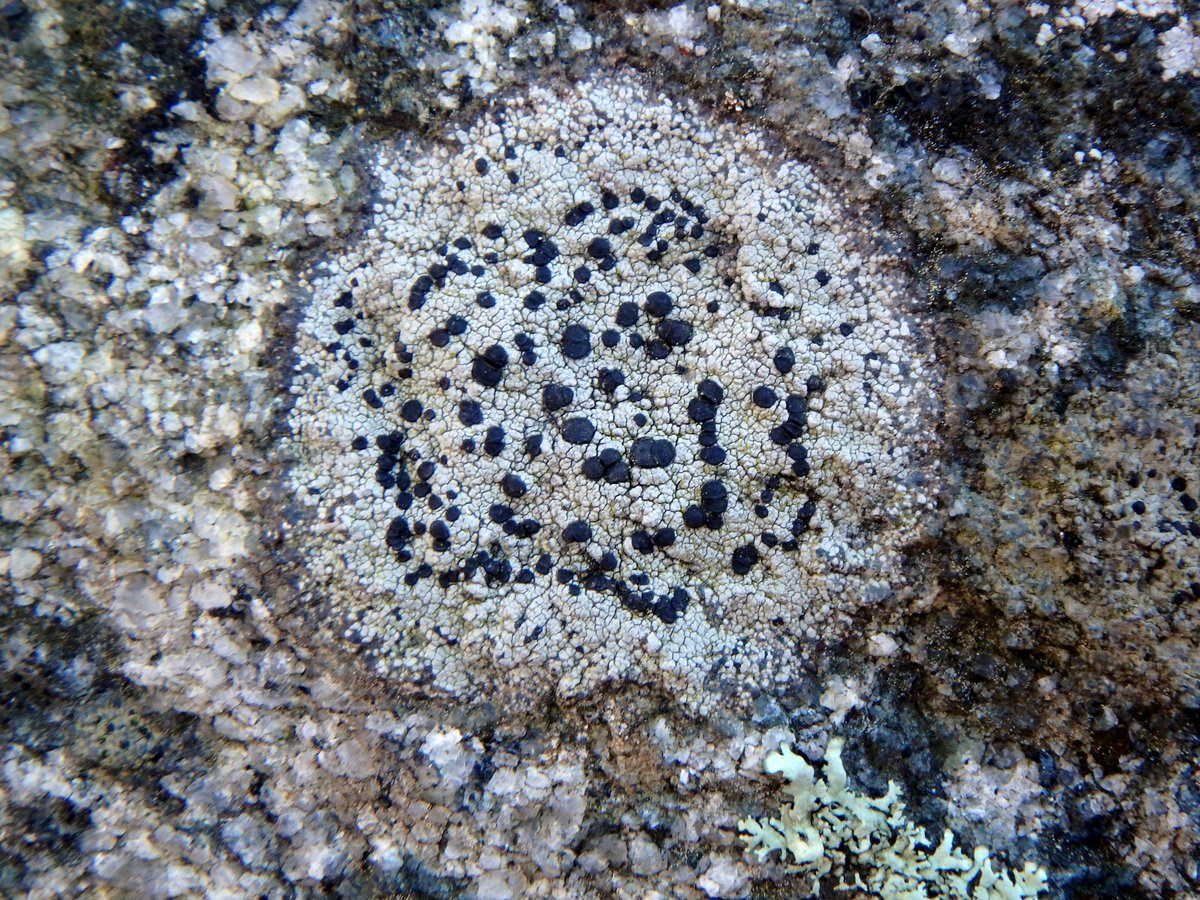

Unlike the spore producing sori on the marginal wood fern (Dryopteris marginalis) which appear on the leaf margins, the sori on spinulose wood ferns appear between the midrib and the margins. Spinulose wood fern cross breeds the with both the marginal wood fern and the Intermediate wood fern (Dryopteris intermedia) so it can get confusing. This one was producing spores and as usual it made me wonder why so many ferns, mosses, lichens and clubmosses produce spores in cold weather. There has to be some way it benefits the continuation of the species but so far I haven’t discovered what it is.

Partridgeberry (Mitchella repens) is a common evergreen groundcover that grows along the trail. Small, heart shaped leaves on creeping stems grow at ground level. In spring it has white trumpet shaped flowers that grow in pairs and in the fall it has bright red berries which are edible but close to tasteless. I leave them for the turkeys, which seem to love them. My favorite parts of this plant are the greenish yellow leaf veins on leaves that look as if they were cut from hammered metal. I have several large patches of it growing in my yard.

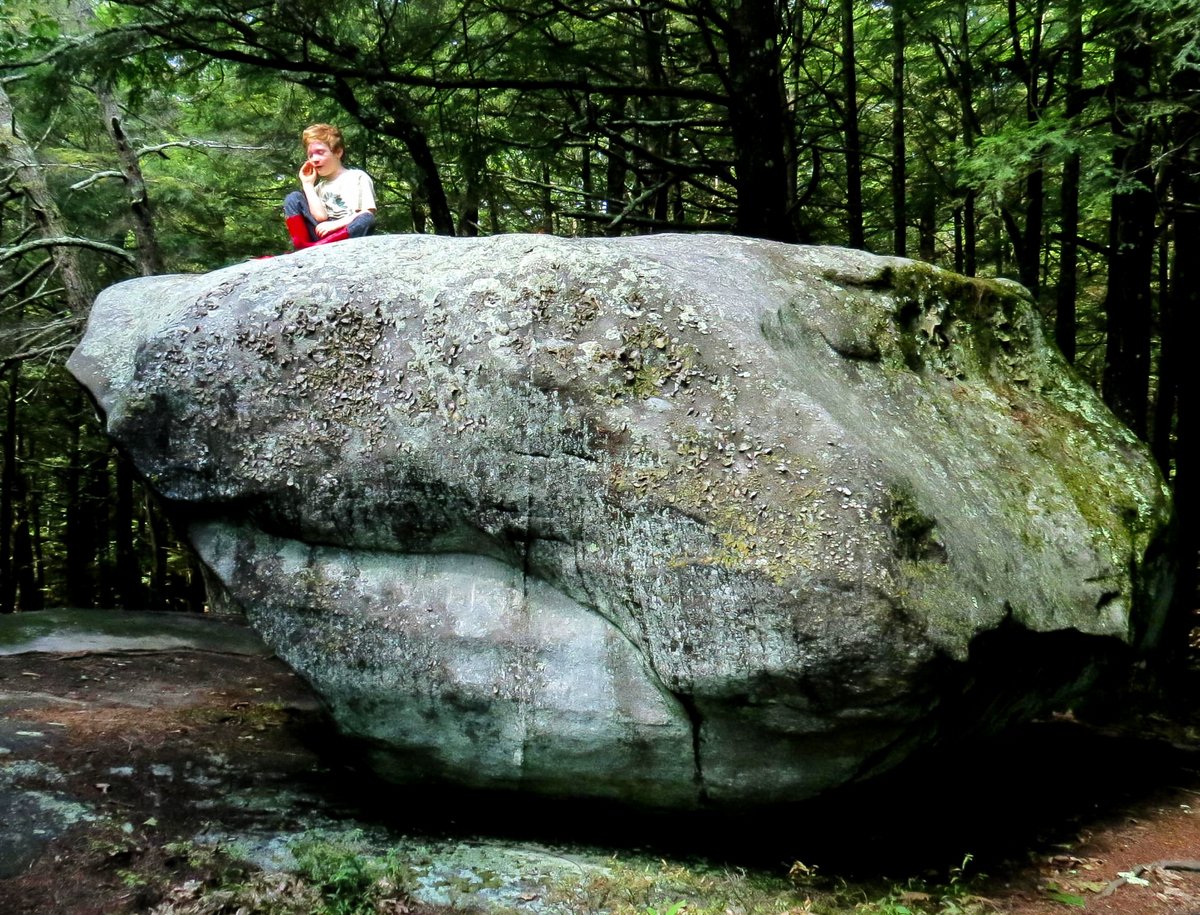

Here was a downed tree; the first of many, I guessed. There have been lots of trees falling across the road this year and in some cases they are almost impossible to bypass.

I always stop to look at the branches of newly fallen trees to see what lichens lived on them. This one had a lichen garden in its crown. Mostly foliose (leafy) lichens, which were in fine form due to the recent wet weather. Lichens don’t like dry weather so I haven’t bothered them much this summer.

The big light colored lichen you saw in the previous shot was I believe a hammered shield lichen (Parmelia sulcata), so named because it looks like it was hammered out of a piece of metal. These lichens are on the rare side here but I see them occasionally, always on trees. Hammered shield lichen is said to have a large variety of named varieties and forms, so it can be tough to pin down. Fruiting bodies are said to be rare and I’ve never seen them. It is also said to have powdery, whitish soredia but I’ve never seen them either. Soredia are tiny packages of both fungus and alga that break off the lichen and they are simply another means of reproduction.

NOTE: A lichenologist helper has written in to tell me that this lichen is actually a crumpled rag lichen (Platismatia tuckermanii) which I’ve been searching for for years. I hope my misidentification hasn’t caused any confusion. I know there are lots of lichen lovers out there.

Though in photos the road looks very long in reality it’s probably only a couple of miles out and back. But it was a nice warm day and there is usually lots to see, so I wouldn’t mind if it was longer.

And here was a huge downed pine that had taken a few maples down with it when it fell. Its root ball was also huge.

Orange crust fungus (Stereum complicatum) is so bright it’s like a beacon in the woods and it can be seen from quite far away on fallen branches. The complicatum part of its scientific name means “folded back on itself” and as can be seen in this photo, that is often just what it does.

I saw some mushrooms squeezing out between the bark and wood of a stump.

I’m not sure what they were; possibly one of the wax cap Hygrocybe clan. In any event they were little and brownish and life is too short to try and identify little brown mushrooms. Even mycologists are too busy for them and toss them into a too hard basket labeled LBMs.

These larger examples on a different stump might have been late fall oyster mushrooms (Panellus serotinus) but I didn’t look at their undersides so I’m not sure. My color finding software sees salmon and coral pink, while I see orange. An orange mushroom in clusters on wood at this time of year often means the Jack O’ Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus illudens), which is toxic. That’s why you should always look at their undersides and other features if you want to eat them.

And the mosses were so beautifully green!

Finally you come to the small stream you have to cross if you are to go on. I made it without falling once again, but I always wonder if this will be the time. Some of those stones are tippy.

Once I crossed the stream I saw that a new beaver dam had appeared since the last time I was here.

Recently chewed alders told me the beavers were very active. On small trees like these they leave a sharp cut that looks like someone has cut the tree with loppers. Their teeth are very sharp.

The beaver pond had grown deeper and wider.

You can tell the beaver pond wasn’t here when this land was farmed, probably in the 1800s. You don’t build stone walls under water.

The pond banks had breached in several places and if left to their own devices the beavers will flood this entire area.

I don’t worry about what beavers are doing because they do a huge amount of good for the ecosystem, but since all of this is very near a highway the highway department will eventually destroy the beaver dam so the highway isn’t flooded. I didn’t worry about that either; it has become part of the cycle. Instead I admired the beautiful red of the winterberries (Ilex verticillata). They are a native holly that love wet feet and the beavers are making sure that they get what they love. By doing so you can see that the beavers, in a round about way, are providing food for the birds. They also create and provide habitat for a long list of animals, amphibians and birds. This area would be very different without them.

It’s amazing how quickly nature consumes human places after we turn our backs on them. Life is a hungry thing. ~Scott Westerfeld

Thanks for stopping in.