🌱 Quill 🌱 he/him 🌱 hi plants are my life and i like shitposting. they say to follow ur dreams so here i am, a combination of everything i love 🌱 Iowa corn hell pride 🌱 https://youtu.be/cjV7Fbz4yq8

🌱 Quill 🌱 he/him 🌱 hi plants are my life and i like shitposting. they say to follow ur dreams so here i am, a combination of everything i love 🌱 Iowa corn hell pride 🌱 https://youtu.be/cjV7Fbz4yq8

(okay so this is gonna be a long post bc i took and then TAed a class partially about mosses so anybody who doesnt want a moss crash course should start scrolling now)

formally mosses are the only things in the taxonomic division Bryophyta. informally you’ll hear people refer to mosses as well as liverworts (Marchantiophyta) and hornworts (Anthocerotophyta) as ‘bryophytes’, because for a long time the three were all lumped into that division together, and people got used to using the term ‘bryophyte’ interchangeably with ‘nonvascular plant’.

that term, ‘nonvascular’, is the big distinguisher for these three. basically these plants are very, very ancient lineages, as in liverworts are suspected to be the first plants to crawl out of the primordial ooze, and they don’t have proper, distinguishable vascular tissues (xylem and phloem are the main ones in all vascular ‘higher’ plants that forms the other 99% of the plant kingdom). they have primitive vascular tissues, but they’re not hefty enough to do much in terms of moving water through the plant. their ancestors weren’t able to get very far from the shore of the sea/away from a water source, because they needed to stay wet and depended on water for reproduction. while the latter is still true, modern mosses can be very well adapted to dry areas, and some are able to completely desiccate themselves and go dormant for long periods of time before being revived with the next rain.

out of this triad of Old Lads, mosses and (leafy) liverworts look the most similar and get mixed up the most (there are ‘leafy’ liverworts and ‘thalloid’ liverworts. thalloid liverworts are wack and do not look like mosses at all). the differences between them are incredibly minute, but (leafy!!) liverworts, to be crude about it, are kind of proto-mosses with simpler physiologies. a common signifier is that leafy liverworts almost never have a costa (a single vein running down the middle of each leaf) and instead have completely smooth leaves, whereas costas are common in mosses. other differences are infuriatingly consequential (’oh, but see this liverwort has a costa but it’s still a liverwort, don’t ask questions’) and honestly i have no idea who decided which plants were leafy liverworts and which plants were mosses, but that’s just me.

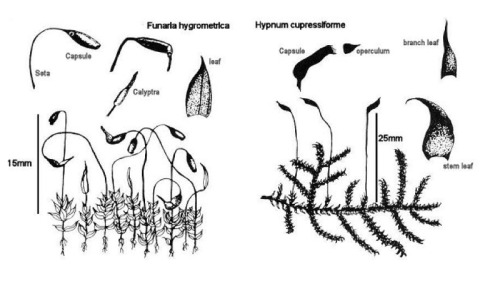

i should mention also that mosses, like liverworts, are split into two major groups based on their growth forms: ‘acrocarpous’ mosses are mosses who’s stalks stand straight up, and ‘pleurocarpous’ mosses are mosses who’s stalks crawl along the ground. acrocarpous mosses won’t have branching stalks, whereas pleurocarpous mosses can. an example of an acrocarpous moss is on the left, an example of a pleurocarpous moss is on the right:

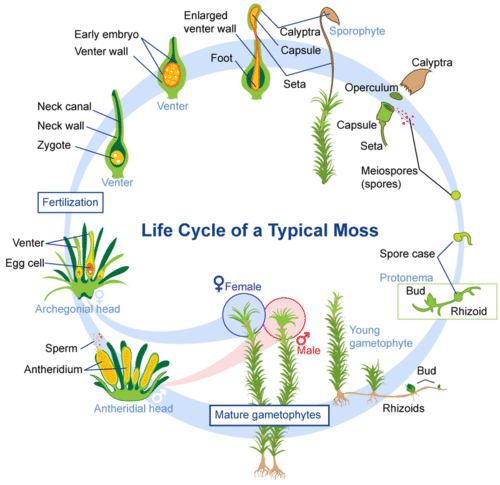

mosses do not flower. they reproduce by spores. liverworts and hornworts also reproduce by spores, not flowers. it’s easy to forget that ferns, which are like, THE original Old Lads, are actually younger than these lineages and are considered vascular plants for having more advanced xylems and phloems, and flowers didn’t come for several hundred million years after them. mosses reproduce by producing male and female reproductive organs on the parent plant, with sperm and eggs being produced in each, respectively. the sperm can swim, and fertilize the female eggs, which then sprout while still on the plant into stalks (seta) with capsules on the end. these capsules are full of spores, and when the plant is ready the tip falls off and lets the spores catch the breeze, and hopefully a few will find suitable conditions to sprout into new mosses. the entire cycle looks like this:

okay. habitats. mosses live on such a small scale that it’s best to think of how they live in terms of microhabitats instead of habitats, meaning that like, if you look at a forest from the road, that’s one habitat, but the mosses in that forest are experiencing a ton of microhabitats within that habitat. a moss that grows on the side of the tree will dry out really fast after it rains, so a species that might be more susceptible to overwatering may survive better on a tree trunk than at the base of the tree; both places, although at the same physical location, provide way different conditions and will be favored by different species.

a moss that grows in a crack on the pavement will probably be absolutely swimming in water when it rains, so it’s probably a species that’s either fine with being submerged (and regularly trampled) or otherwise tolerant of it. a moss growing under a decaying log will have more shelter than others, and will have less airflow and higher humidity. if you’re a moss living on the bark on the side of a stump, and that bark rots enough to one day peel away and fall off, that might be absolutely devastating to you despite only losing like one inch of area, but the newly-exposed rotting hardwood creates a new microhabitat that might be favored by other species. it’s one of those things that you really start to notice once you start thinking about it.

now. i want to end this post with the world’s tallest self-supporting moss. my lichen and bryophyte professor has seen this moss in person and has confirmed it is really just Like That. the moss is the acrocarpus Dawsonia superba, and it’s native to Oceana. the tallest ever found was in Borneo, and was a meter tall. here’s a picture of it by gailtv on iNatrualist, observed december 17th, 2015 in New Zealand:

Chonkers™. now, the largest moss that doesn’t support itself is a pleurocarpous moss-vine, Spiridens reinwardtii, also native to Oceania, which crawls up tree trunks and can grow to a length of 3 meters. here’s one spotted by dantn, also on iNaturalist, observed august 23rd 2006 in northern Indonesia (it’s the one that looks like artificial christmas tree branches. that’s one single moss):

end note: i think i’ve recced this book on here before but a really good book to learn more about mosses is Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses by Robin Wall Kimmerer, which is a required book for the course i learned all this in and helped teach later. it’s not a field guide (for that I would recommend finding a moss and liverwort ID guide for your region), but it’s just about mosses in general and essays about how great and wild they are. VERY much worth it

catsrcoolyeet reblogged this from botanyshitposts

catsrcoolyeet reblogged this from botanyshitposts  catsrcoolyeet liked this

catsrcoolyeet liked this  sandwlch liked this

sandwlch liked this  streamlass reblogged this from a-bed-of-moss

streamlass reblogged this from a-bed-of-moss  a-bed-of-moss reblogged this from botanyshitposts

a-bed-of-moss reblogged this from botanyshitposts  a-bed-of-moss liked this

a-bed-of-moss liked this  wildappalachia reblogged this from botanyshitposts

wildappalachia reblogged this from botanyshitposts  stuckwith-harry liked this

stuckwith-harry liked this  weekendafternoon reblogged this from botanyshitposts

weekendafternoon reblogged this from botanyshitposts  pleb119 liked this

pleb119 liked this  you-just-got-feldsparred liked this

you-just-got-feldsparred liked this  dexofone reblogged this from botanyshitposts

dexofone reblogged this from botanyshitposts  laberrant liked this

laberrant liked this  lucinata reblogged this from brightsuzaku

lucinata reblogged this from brightsuzaku  lucinata liked this

lucinata liked this  brightsuzaku reblogged this from botanyshitposts

brightsuzaku reblogged this from botanyshitposts  girlbossfailure liked this

girlbossfailure liked this  girlbossfailure said:

OMG I NEED THIS

girlbossfailure said:

OMG I NEED THIS  carobnjakstapic liked this

carobnjakstapic liked this  aghostwriting liked this

aghostwriting liked this  ghoulfrnd-mtrl reblogged this from hes-a-plant

ghoulfrnd-mtrl reblogged this from hes-a-plant  ghoulfrnd-mtrl liked this

ghoulfrnd-mtrl liked this  hes-a-plant reblogged this from botanyshitposts

hes-a-plant reblogged this from botanyshitposts  avarice-keeps-me-alive reblogged this from botanyshitposts

avarice-keeps-me-alive reblogged this from botanyshitposts  avarice-keeps-me-alive liked this

avarice-keeps-me-alive liked this  frenzis-little-cottage liked this

frenzis-little-cottage liked this  gloupysoupy liked this

gloupysoupy liked this  sundaysclown liked this

sundaysclown liked this  yelenasvestpockets liked this

yelenasvestpockets liked this  whatssoaweful liked this

whatssoaweful liked this  garbungled liked this

garbungled liked this  botanyshitposts posted this

botanyshitposts posted this