Nymphicus hollandicus

By Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Etymology: Nymph Birds

First Described By: Wagler, 1832

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Psittaciformes, Cacatuoidea, Nymphicinae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

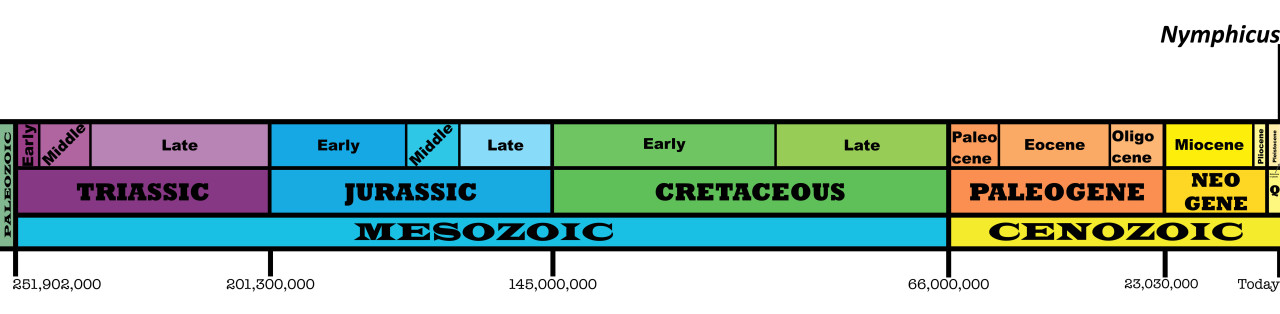

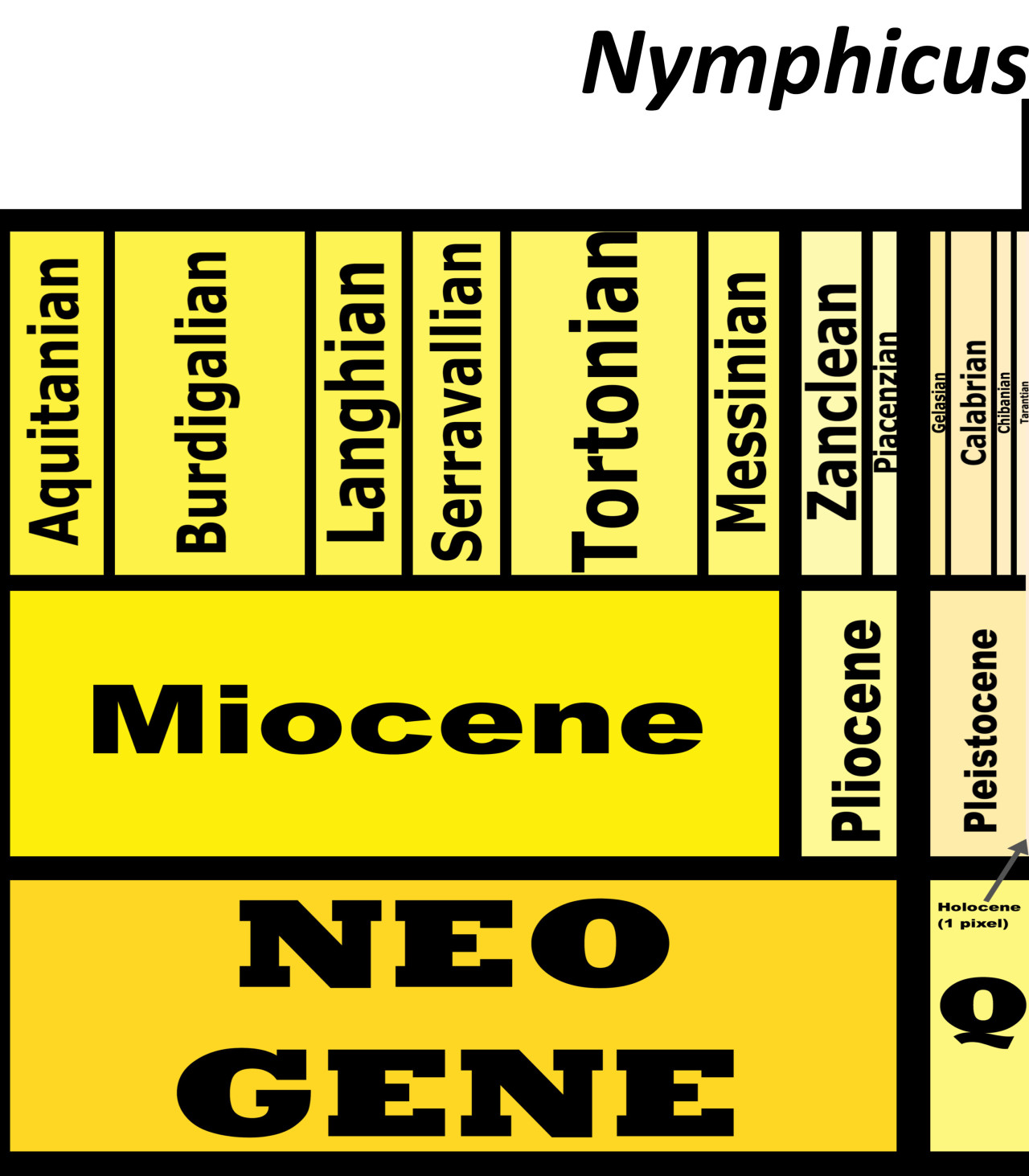

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Cockatiels are originally known from the bulk of Australia

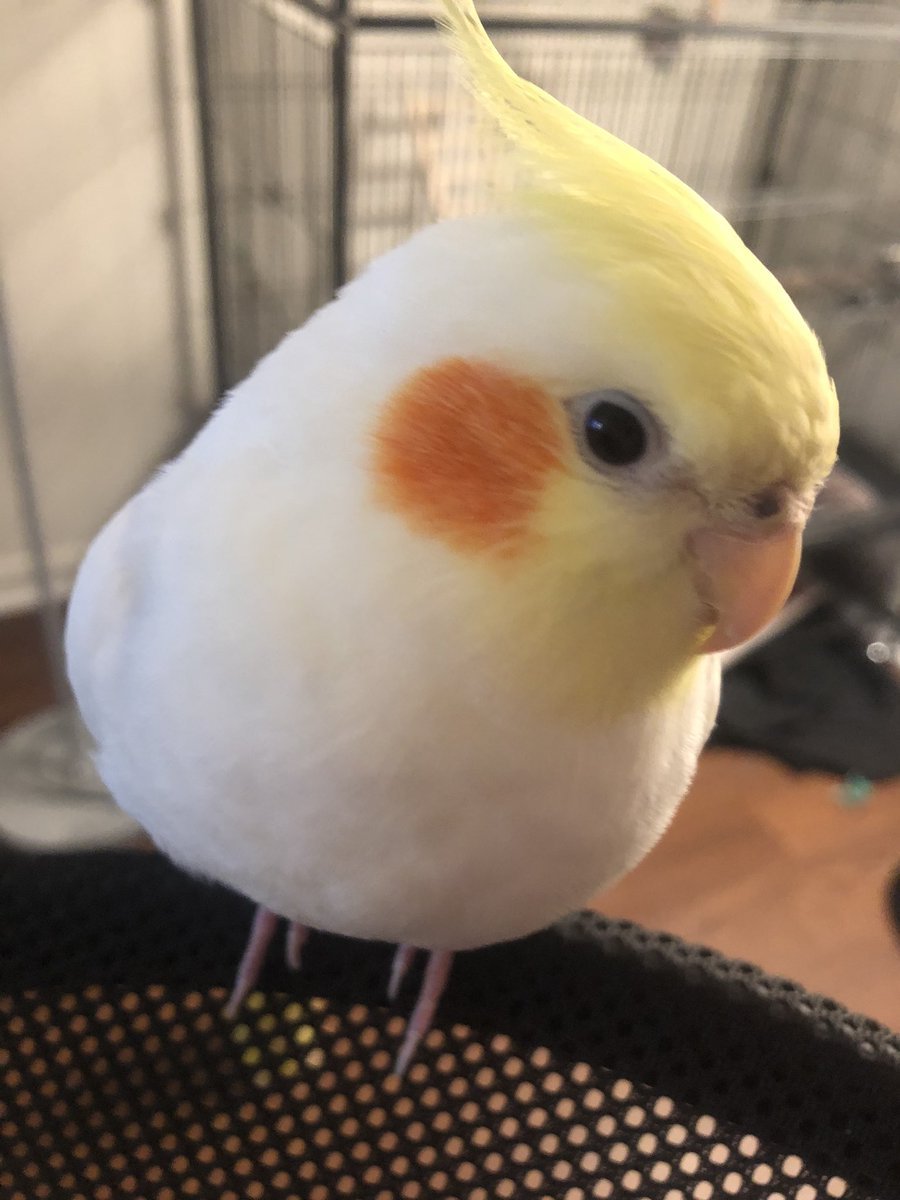

Physical Description: Cockatiels are medium sized birds, ranging between 29 and 33 centimeters in total body length. Wild Cockatiels are grey all over their bodies, with white patches on their wings. The males have bright yellow heads with orange cheek patches, and long yellow crests of feathers coming off of the tops of their heads. The females are usually more grey in the head region, with a duller orange cheek patch, and a grey crest. They have extremely long tail feathers and very large, broad wings. They usually weigh between 80 and 100 grams. Semi-domesticated individuals of this species can come in a wide variety of color morphs that are based on the wild-type colors, but not exactly the same: some will be yellow-ish all over, some will be entirely white; some will lack the orange cheek patches and have grey or white heads; some will be more spottled, and so on. There are an estimated 22 color mutations in cockatiels, with many being very distinctively different. In general, males are more brightly patterned than females, and have bigger crests; there are exceptions to this rule, of course, all over the color spectrum.

By Ben Cordia, CC BY-SA 4.0

Diet: In the wild, Cockatiels feed mainly on seeds and grain, especially from crops and native fields and plains, where grass seeds are fed upon. In captivity, Cockatiels should be fed a varied diet of pellets, fresh vegetables, whole grains, some fruit, and the occasional seed for treats.

By Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Behavior: Cockatiels in the wild will feed twice a day by foraging on the ground, scurrying about in a waddling fashion to look for the seeds and grains they prefair. Large flocks of tens to hundreds or even thousands of birds will gather depending on how much food is available in any given spot, and are occasionally joined by budgies at especially fertile lands. Their waddle walk is offset by the fact that they are extraordinarily powerful fliers, able to move very fast and powerfully with rapid flaps of their wings, using the tail to steer. They will migrate nomadically, following the presence of seeds and - thus - usually following rain patterns. Because they follow water, they oftentimes will reach the coast in their migrations. At night, they will sleep in available trees, perched in branches with no real preference as to what sort of tree they sleep in.

BY Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

Cockatiels are extraordinarily loud birds, making a variety of calls to one another to ensure that the flock stays together. To just chirp at each other, they’ll make sort of yipping calls as they go about their day. When a member of the flock is lost, they will scream extremely loudly to find them again, calling out “EEP” at the top of their lungs until the flock member is located. While flirting, they will unfurl their wings ever so slightly, forming a heart shape; sticking their neck out, they will perform a flirtatious call (which can vary somewhat) at the object of their affections. They often bob their heads and bodies while doing this. Sometimes they’ll practice their singing into the air, and will hold up one of their feet to do so, singing at it like they’re holding a microphone. They will extend their crest out all the way while curious, and cluck while exploring a specific environment. When alarmed, their body will go extremely taught, their neck stuck out all the way; if danger is present, they’ll fly away quickly and make very loud sounds to the rest of the flock to promote everyone escaping from the situation.

By Jim Bendon, CC BY-SA 2.0

In the wild, cockatiels breed usually in the late autumn or winter, nesting within tree hollows. They are very protective of their nesting sites and will scream at any intruders. They can form lifelong pairs or be polygamous in terms of breeding behavior. Both sexes will protect the eggs and bring each other food; the clutches are usually one to seven eggs in size, and are incubated for twenty days. The chicks are usually very naked with some yellow down, and are largely altricial; they will stay protected for five weeks and are guarded by the parents. They then mature and become part of the nomadic flocks, sticking close to their family members for the first month or so. Cockatiels reach sexual maturity at around 1 year old, and full skeletal maturity at 2 years. They can live up to 25 years on average, though many individuals have reached past 30 years of age with proper care.

By Meig Dickson

Ecosystem: In the wild, Cockatiels live in arid and semi-arid open habitats such as savanna, scrubland, open woodland, grassland, and more outback habitats. They will stay close to sources of water but do not need them as much as other parrots; and they are often found associated with extensive cropland and farms. They are usually not found in the most fertile and wet corners of Australia, or the deepest parts of the Australian desert, or the Cape York Peninsula.

By Meig Dickson

Other: Cockatiels are some of the most common birds in Australia, with an estimated population of around one million individuals; this, plus them showing no real drops in population, makes them not vulnerable to extinction at this time. They are occasionally regarded as pests, especially by farmers. However, the main interaction humans have with Cockatiels is via aviculture.

By Meig Dickson

Cockatiels are the second most popular pet parrot after budgies, and one of the most common pet caged birds out there. While individuals are occasionally imported from Australia from time to time, most Cockatiels sold or adopted at this point are descended from many generations of breeding programs. Breeding efforts have turned pet cockatiels into nearly domesticated animals, inhabiting that weird grey area between tame and domestication. As such, at-home species have different colors and behaviors. They tend to trust humans more, especially when they are hand-fed by their breeders. They are extremely intelligent animals and are able to learn tricks. They require extensive space, toys, and out-of-cage time to live happy lives, and need a varied diet to avoid biological problems such as fatty liver disease. Though not an easy companion animal to own by any stretch of the imagination, cockatiels (and budgies) are well on their way to being truly domesticated, rather than just an exotic animal that’s at home in human spaces. Extremely social animals, they do best with other members of their species in a large cage, rather than being alone in a smaller space. Cockatiels are kept entirely for companionship; they are not bred for any other purpose, though with their powerful and agile flight style they may be shown off in bird shows.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Adams, M; Baverstock, PR; Saunders, DA; Schodde, R; Smith, GT (1984). “Biochemical systematics of the Australian cockatoos (Psittaciformes: Cacatuinae)”. Australian Journal of Zoology. 32 (3): 363–77.

Astuti, Dwi (2011). “Phylogenetic relationships within Cockatoos (Aves: Psittaciformes) Based on DNA Sequences of The Seventh intron of Nuclear β-fibrinogen gene” (PDF). Jurnal Biologi Indonesia. 7 (1): 1–11.

Rowley, I. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Flegg, Jim (2002): Photographic Field Guide: Birds of Australia. Reed New Holland, Sydney & London.

Martin, Terry (2002). A Guide To Colour Mutations and Genetics in Parrots. ABK Publications.