Sunday, March 25, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - Looking into the sprial

Next week's post is going to be really good, but it's also going to be next week. Here's a little taster of a post I didn't leave myself a enough time to write today - a close-up of of the shell of native (Allodicsus sp.) land snail:

Check out Aydin Orstan's post about the protoconch and a few other useful terms for describing shell shapes.

A snail's shell is a complete record of that shell's growth. If you look closely at this photo, you can see that the raised pattern on the shell (the "sculpture") changes. The inner-most coils have "spirals" that run in the same direction as the growth of the shell, while the outer shells have "ribs" that run across it. The point at which this pattern changes marks the end of the snails embryonic growth (called the protoconch) and the beginning of its juvenile and adult growth (the teleoconch). There isn't always a change in sculpture at the point the protoconch gives way to teleoconch, but there is usually some sort of demarcation.

The shape, size and sculpture of snail shells is an important character for the taxonomy of snails - this one is about 0.8 mm wide, which, combined with the sparse spiral pattern it bears fits with the desctiption of A. kakano.

Check out Aydin Orstan's post about the protoconch and a few other useful terms for describing shell shapes.

Labels: native snails, sci-blogs, snails, sunday spinelessness

Friday, March 23, 2012

On the radio

David McMorran from the Department of Chemistry here at Otago hosts a fortnightly radio show, which talks about postgraduate research in the Division of Science. I was the guest last week, so if you want to hear me talk about taxonomy, the challenge that the world's biodiversity represents for scientists and a little bit about my land snails the audio for interview is up here.

I find it very hard to listen to recordings of my own voice, but I did manage to get through that audio once. So, I should say that "a bloke called Ernst Mayr" is perhaps taking the antipodean lack of reverence for important people a little too far. And I don't know what I said the Galapagos has nightingales - it was the Galapagos mockingbirds that Darwin was interested in.

I was a little bit nervous about doing the interview, but in the end far the most difficult part of the whole process was trying to find three songs so share. Here's one that missed the cut, decided it was just a bit too cute:

I find it very hard to listen to recordings of my own voice, but I did manage to get through that audio once. So, I should say that "a bloke called Ernst Mayr" is perhaps taking the antipodean lack of reverence for important people a little too far. And I don't know what I said the Galapagos has nightingales - it was the Galapagos mockingbirds that Darwin was interested in.

I was a little bit nervous about doing the interview, but in the end far the most difficult part of the whole process was trying to find three songs so share. Here's one that missed the cut, decided it was just a bit too cute:

Sunday, March 18, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - Gotcha!

I only have moment to spare today, so I thought I'd share a life and death moment from the garden.

The fearsomely-spiked creature photographed above is the larva of a ladybird (that is, a beetle of the family Coccinellidae), specifically the New Zealand and Australian native species Apolinus lividigaster. It's meal is an ahpid, though I couldn't tell you which species.

Learning that ladybirds are vicious predators (adults have more or less that same tastes as their larvae) might go some way to undermine ladybirds' status as a "cute" insect that escapes the "yuck" reaction so many of their kin seem to evoke. But it's worth remembering that ladybirds are very useful. Most species specialise in eating plant-sucking insects like aphids and scales, and so can be a boon to gardeners. On a larger scale, predatory ladybirds are often introduced as "biological" control to help keep pest numbers low.

Learning that ladybirds are vicious predators (adults have more or less that same tastes as their larvae) might go some way to undermine ladybirds' status as a "cute" insect that escapes the "yuck" reaction so many of their kin seem to evoke. But it's worth remembering that ladybirds are very useful. Most species specialise in eating plant-sucking insects like aphids and scales, and so can be a boon to gardeners. On a larger scale, predatory ladybirds are often introduced as "biological" control to help keep pest numbers low.

Labels: beetle, coccinellidae, environment and ecology, photo, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness

Thursday, March 15, 2012

Chimps are our closest relatives... but not for all of our genes

Ladies and genetlemen, we have the gorilla genome. You reaction to this news is probably determined by what you do for a living. If you write the headlines for major news services you will convince yourself that this result will, in some utterly undefined way, teach us about what it is to be human. Just about everyone else will develop a case of Yet-Another-Genome Syndrome. The gorilla is, by my count, the 51st animal to be added to the full-genome club and the last of the great apes (joining humans, chimps and orangutans). More to the point, the publication of a new genome sequence doesn't, by itself, tell us all that much. The real achievement in a "genome of x" paper is the creation of a resource that scientists will continue to work from for decades. The analysis that comes with it is really just a first pass.

But there was one very cool result to come from the analysis of the gorilla genome. About 15% of our genes are more closely related to their counterparts in gorillas than they are to the same genes in chimps.

That sounds suprising. People are always going on about how humans and chimps are ninety-nine-point-some-magic-number percent identical, and there are exactly two scientists in the world who think chimps are not our closest relatives (Grehan and Schwartz, 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02141.x). Have we been wrong? And how can 15% of a genome show one pattern while the rest shows another?

To understand what's going on, we need to remember where species come from. Species start forming when populations stop sharing genes which other. When genetic changes in one population can't filter through to another, those two populations are capable of evolving apart from each other and so can become distinct and take on the various characters that we use to tell species apart. So, new species only become different as they start to evolve apart, but they start of with a more or less random sampling of the genes in the ancestral population from which they descend. If we want to understand what's going with the gorilla genome, we need to understand the history of those genes.

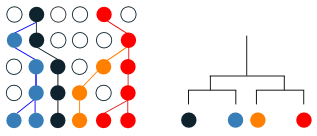

In most populations at least some genes come in distinct "flavors" (technically called alleles) . So, for instance we all have a gene called MC1R, but some of have an MC1R allele that is associated with red hair, and others have alleles that usually lead to dark hair. We inherit our genes from our parents, so each allele has a history that stretches back through time. If we look at modern populations we can use genetic differences between alleles to reconstruct that evolutionary history. Here's a simplified history of four alleles, in a very small population (if you re-trace the lineages you see they fit the tree to the right):

But there was one very cool result to come from the analysis of the gorilla genome. About 15% of our genes are more closely related to their counterparts in gorillas than they are to the same genes in chimps.

That sounds suprising. People are always going on about how humans and chimps are ninety-nine-point-some-magic-number percent identical, and there are exactly two scientists in the world who think chimps are not our closest relatives (Grehan and Schwartz, 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02141.x). Have we been wrong? And how can 15% of a genome show one pattern while the rest shows another?

To understand what's going on, we need to remember where species come from. Species start forming when populations stop sharing genes which other. When genetic changes in one population can't filter through to another, those two populations are capable of evolving apart from each other and so can become distinct and take on the various characters that we use to tell species apart. So, new species only become different as they start to evolve apart, but they start of with a more or less random sampling of the genes in the ancestral population from which they descend. If we want to understand what's going with the gorilla genome, we need to understand the history of those genes.

In most populations at least some genes come in distinct "flavors" (technically called alleles) . So, for instance we all have a gene called MC1R, but some of have an MC1R allele that is associated with red hair, and others have alleles that usually lead to dark hair. We inherit our genes from our parents, so each allele has a history that stretches back through time. If we look at modern populations we can use genetic differences between alleles to reconstruct that evolutionary history. Here's a simplified history of four alleles, in a very small population (if you re-trace the lineages you see they fit the tree to the right):

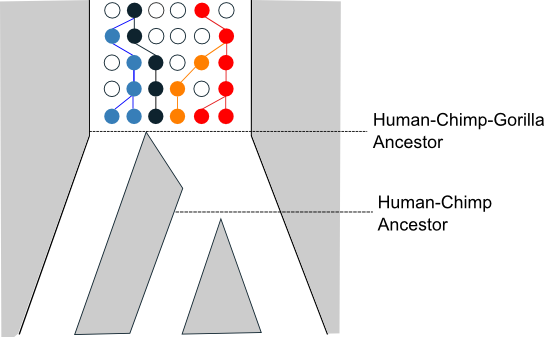

So, what happens when a population with different alleles starts to diverge into new species:

The genetic lineages will keep on evolving down through the new tree, but now lineages will never cross the barriers to gene flow that are driving speciation. Often, the genetic lineages in the ancestral population will "sort" in such a way that when you trace the genetic lineages within a species back you arive at a member of that species (not an individual from the ancestral population). In that case, the genetic relationships (which we'll call "gene trees) will be the same as relationships between species ("species trees"):

But population genetic theory tells us we won't always get such a simple pattern. For recent or repeated and rapid speciation processes there might not be time for the genetic lineages to sort. The gene tree can be different from the species tree:

Exactly this process has happened with the gorilla genome. The genetic lineages hadn't sorted before the human-chimp split so some of our genes are more closely related to gorilla ones than chimps ones. This phenomenon might tell us something about the evolution of the great apes . The time that it takes for lineages to sort is proportional to the population size of the organisms through which the lineages are evolving. Processes that effectively limit the population size (like natural selection, which results from relatively few individuals contributing to the next generation) might leave a pattern in the way lineages have sorted. The authors of the gorilla genome paper use this prediction to search for and find areas of the gorilla genome that may have been subject to strong selection after the population went its own way.

So called "incomplete lineage sorting" is a problem for people like me who aim to reconstruct the evolutionary history of species using genetic data. Although we've always known this problem existed, we've only recently been able to extend population genetics theory to actually infer the history of species for gene trees even when those gene trees are unsorted. It's important we have these methods, because it's actually predicted that most genetic lineages will be unsorted for about 1 million years after speciation starts - often all we have are unsorted genes and it's nice to be able to extract some information from them.

So called "incomplete lineage sorting" is a problem for people like me who aim to reconstruct the evolutionary history of species using genetic data. Although we've always known this problem existed, we've only recently been able to extend population genetics theory to actually infer the history of species for gene trees even when those gene trees are unsorted. It's important we have these methods, because it's actually predicted that most genetic lineages will be unsorted for about 1 million years after speciation starts - often all we have are unsorted genes and it's nice to be able to extract some information from them.

The Gorilla Genome paper is

Scally, A., Dutheil, J. Y., Hillier, L. W. et al. (2012) Insights into hominid evolution from the gorilla genome sequence. Nature, 483, 169-175 doi:10.1038/nature10842

Labels: evolution, genomes, phylogenetics, sci-blogs, science

Sunday, March 11, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - Libera fratercula

If you are a cricket fan you'll know what sort of weather we've had in Dunedin - wet and grey with a chance of denying New Zealand a glorious victory.* The gloomy picture outside the window is made worse for by the fact I've spent most of the afternoon sorting through pictures taken for my fieldwork in the Cook Islands. So, between the carefully numbered photographs of the snails that went on to be the basis of my thesis I'm met with scenes from a tropical paradise:

There are also some interesting critters in the "official" photos - like this snail:

That's Libera fratercula Pease, 1867 and if you believe that subspecies are a meaningful category you can call in L. fratercula rarotongensis Solem, 1976. The genus Libera is part of one of the most important land snails families in the Pacific - the Endodontidae. These tiny snails (most have shells only a few millimeters across) are found on most islands in Pacific and in some cases underwent very large evolutionary radiations. In fact, there were so many species that Alan Solem seemed to have trouble coming up with names for them in his 1976 monograph . Solem introduced the genera Aaadonta and Zyzzyxdonta (so named because he believed them to be morphological opposites, which should appear at opposite ends of his work) and named one species Baa humbugi (the genus named for a part of Fiji and the species name the result of an "irresistible impulse").

It's not really possible to write about Pacific land snail faunas in the present tense - it's quite likely most of the species Solem described are now extinct as the result of habitat destruction and introduced pests. In the Cooks there were two major radiations, the Sinployea and Minidonta of Rarotonga, both now severaly eroded. The Cook's Libera are less diverse, but also have an interesting evolutionary history. There are forest-dwelling Libera species in many islands in the SW Pacific, and Rarotonga was no different with one species L. cavernula making its living in the vegetation. Libera fratercula (the handsome species photographed above) appears to be the closest relative of L. cavernula (that is, the two species arose within Rarotonga) but at some stage this lineage gave up on forest and started living on the beach. Specifically, L. fratercula lives in the piles coral rubble that accumulate on Rarotonga's beaches, having been broken away from the island's fringing reef. This is a harsh environment, with changes in temperature, saltiness and moisture occuring all the time - but the switch appears to have worked out for L. fratercula, which still has quite large populations around island whereas L. cavernula is now missing presumed extinct.

Rarotonga has plenty of coral rubble, but the other islands in the Southern Cook Islands are basically made of coral rubble. Mitiaro, Mangia, Atiu and Mauke are all small islands that have already gone through the all the steps of the typical life cycle of a pacific island: a fiery birth as a volcano; subsequent erosion into an ever smaller, flatter island; treading water as an atoll and finally dipping below the surface for ever. The islands of the Southern Cooks got another shot at life when, about 2 million years ago, fresh volcanic activity lifted the crust on which they sit and thrust the fossilsed remains of their coral reefs above the surface. These so-called makatea islands have no shortage of coral rubble and the Rarotongan L. fratercula populations live in just the right place to be swept out to sea. It seems that, among the thousands of snails that must have died having been washed out to sea, at least a few washed ashore on the makatea islands and took advantage of all that coral. Libera fratercula has made it to each of these smaller islands and they each have (or at least have had) populations of this species.

There's on more really cool think about about L. fratercula - but I'll have to wait until I take a few more photos (sadlt no field work required) to talk about that one. Here's a close up for the mean time:

*Hey, I can dream....

It's not really possible to write about Pacific land snail faunas in the present tense - it's quite likely most of the species Solem described are now extinct as the result of habitat destruction and introduced pests. In the Cooks there were two major radiations, the Sinployea and Minidonta of Rarotonga, both now severaly eroded. The Cook's Libera are less diverse, but also have an interesting evolutionary history. There are forest-dwelling Libera species in many islands in the SW Pacific, and Rarotonga was no different with one species L. cavernula making its living in the vegetation. Libera fratercula (the handsome species photographed above) appears to be the closest relative of L. cavernula (that is, the two species arose within Rarotonga) but at some stage this lineage gave up on forest and started living on the beach. Specifically, L. fratercula lives in the piles coral rubble that accumulate on Rarotonga's beaches, having been broken away from the island's fringing reef. This is a harsh environment, with changes in temperature, saltiness and moisture occuring all the time - but the switch appears to have worked out for L. fratercula, which still has quite large populations around island whereas L. cavernula is now missing presumed extinct.

Rarotonga has plenty of coral rubble, but the other islands in the Southern Cook Islands are basically made of coral rubble. Mitiaro, Mangia, Atiu and Mauke are all small islands that have already gone through the all the steps of the typical life cycle of a pacific island: a fiery birth as a volcano; subsequent erosion into an ever smaller, flatter island; treading water as an atoll and finally dipping below the surface for ever. The islands of the Southern Cooks got another shot at life when, about 2 million years ago, fresh volcanic activity lifted the crust on which they sit and thrust the fossilsed remains of their coral reefs above the surface. These so-called makatea islands have no shortage of coral rubble and the Rarotongan L. fratercula populations live in just the right place to be swept out to sea. It seems that, among the thousands of snails that must have died having been washed out to sea, at least a few washed ashore on the makatea islands and took advantage of all that coral. Libera fratercula has made it to each of these smaller islands and they each have (or at least have had) populations of this species.

There's on more really cool think about about L. fratercula - but I'll have to wait until I take a few more photos (sadlt no field work required) to talk about that one. Here's a close up for the mean time:

*Hey, I can dream....

Labels: Cook Islands, endodontidae, Libera fratercula, my research, sci-blogs, snails, sunday spinelessness

Sunday, March 4, 2012

Sunday Spinelessness - How could I forget Phronima?

I don't know how, but the other week, when was I trying to introduce the world to some of the ways those crustaceans we call amphipods have adapted to life on earth, I missed perhaps the coolest example of all. Phronima is an amphipod that builds itself a house from the remains of another animal.

Thankfully, other people done a much better job of celebrating these animals than I might have. Matthew Cobb wrote an article on them for Why Evolution is True, focusing especially on the salp whose body is stolen to form Phronima's house (you may be surprised to learn how closely related salps are to us). Mike Bok wrote a post about Phronima and the (perfectly plausible) idea that this creature was an inspiration for the design of the queen from Aliens. Finally, a clip from the extraordinarily awesome Plankton Chronicles series lets you see what I've been going on about with your own eyes:

Be sure to check out the rest of the videos in the series, which includes the flying snails I've blogged about before, a focus on salps in their own right, lots of jellies and all sorts of other wonderful creatures.

Thankfully, other people done a much better job of celebrating these animals than I might have. Matthew Cobb wrote an article on them for Why Evolution is True, focusing especially on the salp whose body is stolen to form Phronima's house (you may be surprised to learn how closely related salps are to us). Mike Bok wrote a post about Phronima and the (perfectly plausible) idea that this creature was an inspiration for the design of the queen from Aliens. Finally, a clip from the extraordinarily awesome Plankton Chronicles series lets you see what I've been going on about with your own eyes:

Be sure to check out the rest of the videos in the series, which includes the flying snails I've blogged about before, a focus on salps in their own right, lots of jellies and all sorts of other wonderful creatures.

Labels: amphipoda, chordata, crustacean, sci-blogs, sunday spinelessness